Dr Sara Walker and Professor Janusz Bialek comment on the recently published Ofgem Decarbonisation Action Plan.

About the authors

Dr Sara Walker is Associate Director of the EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration, Director of the Newcastle University Centre for Energy and Reader of Energy in the University’s School of Engineering. Her research is on energy efficiency and renewable energy at building scale.

Contact details: sara.walker@ncl.ac.uk

Professor Janusz Bialek FIEEE is Professor of Power Energy Systems in the School of Engineering, Newcastle University. Janusz’s background is in power systems but he has closely collaborated with economists, mathematicians and social scientists. He has published widely on technical and economic integration of renewable generation in power systems, smart grids, power system dynamics, preventing electricity blackouts and power markets.

Contact details: janusz.bialek@ncl.ac.uk

While most our worries relate now to the COVID-19 pandemic, we should not forget about the biggest long-term threat to the human race – the climate emergency. In this blog we comment on a recently published “Ofgem decarbonisation action plan” which is a welcome opportunity to see the thoughts of the regulator on the unprecedented need for rapid transitions in our energy systems.

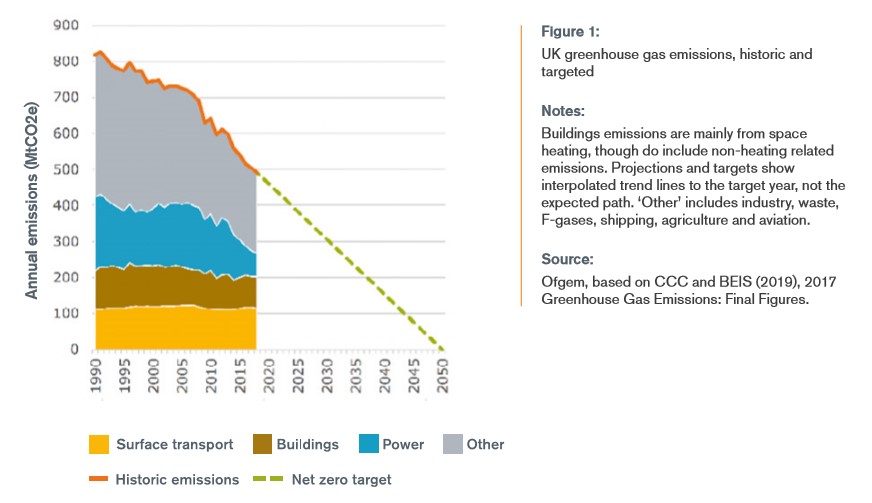

The plan provides some context to the 2050 net zero target with a graph (Fig. 1), showing a 40% reduction in GHG emissions over the period 1990 to 2017. However, the linear reduction proposed from 2017 to 2050 is perhaps misleading the sector in thinking the 27 year 40% reduction to 2017 is similar to the rate of change we now need moving forward. This is not the case, we need an exponential decrease in emissions if we are to come close to the targets set by the Conference of the Parties in Paris. Also it should be appreciated that the closer we get to the net-zero target, the more difficult and costly it will be to reduce the emissions any further. The reason is that once the cheapest means have been exhausted (so-called low-hanging fruits), more expensive ones will have to be used.

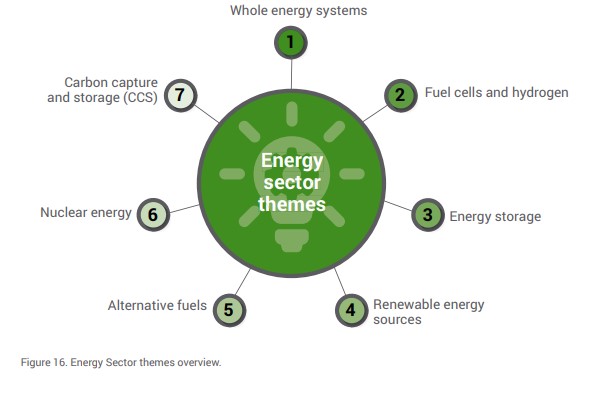

Much of the discussion in the Ofgem plan talks about the need for better interconnection across the energy vectors, and across uses/users. In discussing the power sector, the report refers to key scenarios in the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) report and therefore Ofgem assume Carbon Capture and Storage is needed in order for gas generation to continue. This is an area of contention for the CCC report, since Carbon Capture and Storage technology is currently not commercially available. Alongside gas is nuclear generation, and the Ofgem report assumes nuclear and gas will generate 50% of the UK’s electricity needs. The competitiveness of new nuclear is uncertain, with new offshore wind prices under the Contracts for Difference Scheme being cost competitive with the fixed price of electricity to be generated by the new Hinkley power plant (although one has to acknowledge that nuclear power provides a better security of supply than relatively highly variable and less predictable wind power).

Greater strategic co-ordination and increased investment in generation, network infrastructure, stoppage and other flexibility services are all raised as important in the plan. However, what has not been made clear is a need for a substantial network investment in view of electrification of transport and heat. The report concentrates on the need for proper price controls for network companies but does not address the question by how much the current power network has to be expanded and how to do it in the face of fierce public opposition to construction of new lines.

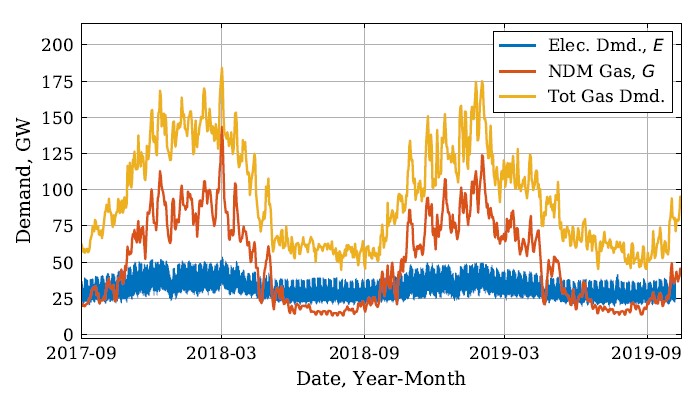

To understand the problem, check the diagram below which shows seasonal variations in the demand for electricity (blue), non-daily-metered gas demand (red) and total gas demand (amber). Clearly gas demand (which largely corresponds to the heat demand) dwarfs the electricity demand both on average and in terms of seasonal variations. The Ofgem plan recommends that decarbonisation of heat be through a combination of heat pumps, hydrogen and heat networks, but that heat pumps will likely contribute the majority of the heat demand.

With regards transport, the Ofgem plan talks about the current >30 million cars in the UK in 2019, and the expected 46m electric vehicles by 2050. “Increased uptake of electric vehicles creates a rare opportunity for a win-win-win for society”. 46m electric cars in the UK by 2050 will mean significant increases in congestion, and significant increase in electricity demand, along side some (albeit reduced) emissions. We would welcome a greater emphasis on public transport, rail and the heavy and light goods vehicle sectors.

Hence electrification of heat (either directly or by heat pumps) and transport would require not only a substantial new generation capacity but also a significant strengthening of both the transmission and distribution networks. But how to do it when any attempts in the past to build a new, or even strengthen an existing, transmission line (see the case of Beauly-Denny line) led to years of arguing and public enquiries? We simply do not have time for that. This is a big elephant in the room.

Flexibility is key to minimise the overall system costs (again check the diagram above to appreciate large fluctuations in energy demand) but the needs are currently highly uncertain given the assumptions around generation from wind, solar and nuclear (all of which are relatively inflexible), along with a potential reduction in load flexibility if significant energy efficiency measures are achieved in future.

Currently the Electricity System Operator (ESO) monitors only transmission connected wind and solar generation and has no direct means of monitoring the distribution-connected generation (DG). This makes it difficult for the ESO to balance the system, and DG was already one of the contributing factors to the GB outage on 9 August 2019. The situation is becoming increasingly difficult to manage, as DG was already 1/3 of installed generation capacity in 2018 and is bound to increase more. In other countries, like e.g. Ireland, the System Operator has visibility of all plants bigger than 5 MW and we see no reasons why GB should be any different.

The Ofgem plan states that regulator has a responsibility to consider the distribution of costs for system changes, particularly for vulnerable customers. Early adopters of technology such as EVs and smart controls are better placed to benefit from energy transitions (since early adopters are usually more wealthy), and those left behind are often in the lowest socio-economic groups. If the costs and benefits of energy transitions fall on different groups, in different locations, at different points in time, then the regulator will need to consider trade-offs in light of its core priorities of protecting the environment, supporting customers, and delivering competition. Perhaps these core priorities need to be weighted, or revised, in light of the Climate Emergency.