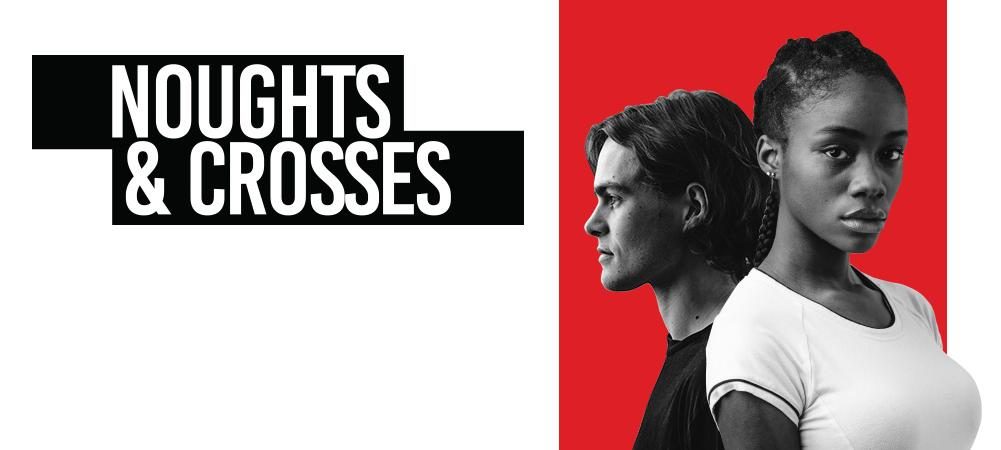

On Wednesday 8th of May, our weekly CLUGG session had a dramatic twist – that evening a group of us had booked to see Sabrina Mahfouz’s stage adaptation of Noughts and Crosses performing at The Northern Stage.

Based on the first book of the bestselling Young Adult dystopian series by Malorie Blackman, Noughts and Crosses makes for an intensely emotional play. With particularly talented performances from Heather Agyepong, refreshingly energetic as Sephy, brought realism to the stage, and Lisa Howard, whose highly empathetic performance as Meggie, Callum and Jude’s mum stole the show; the emotional impact was close to that of Blackman’s novel. Yet, ultimately, it was hampered by the odd pacing of the character development, understandable given the mean task of condensing a complex 440-page novel into a two-hour play; and at times, painful over-acting from some of the performers.

The story is set around two star-crossed teenagers, Callum and Sephy, who are at opposite ends of the spectrum in a society actively segregated by race with Sephy being a privileged Cross and Callum being a disadvantaged Nought. The parallels between how this dystopian society deals with race cast a harsh light on the way in which racism is historically and currently ingrained in modern society with the dystopian twist being that it is people of colour, Crosses, who are privileged over white people, Noughts.

As the story progresses, we see these racial political tensions interfere with the lives of Sephy and Callum increasingly as their stories and that of their families become intertwined. Dealing with a broad range of controversial and sensitive issues, this story is one that doesn’t hold back any punches when tackling sensitive questions and, sadly, remains as relevant now as it did when it was originally written by Blackman in 2001. For instance, a poignant part of the play involves a Nought, a white character, being injured by people protesting the desegregation of a local Cross school which clearly alludes to the 1954 Little Rock desegregation following Brown vs Board. In the play, there is then a quip about the colour of the plaster on the Nought’s face not matching her skin colour and how this is another example of Cross privilege. This issue was brought to media attention in the real world just recently at the end of April when the press picked up on a viral tweet made by Dr Dominique Apollon about his emotion on finding a plaster that matched the colour of his skin for the first time in 45 years. (1)

Clearly then, making connections between the racial segregation in the dystopian world of Noughts and Crosses and the racial injustices present in our world is a priority for Mahfouz. Yet, despite the self-professed want to attract young adult audiences, the play remains heavily intertwined with the curriculum in its promotion. (2) The play comes with its own teaching resource pack produced by Pilot Theatre which features interviews with the cast, pre-show workshop ideas, and video recordings of the play’s key scenes. Most notably, however, is its section on ‘Why Stage Noughts and Crosses Today?’ – a video of teenagers discussing their thoughts on that very question which makes for thought-provoking consideration on the play’s importance and impact. (3) Scholars in the field of children’s literature will be all-too-aware of this difficult balance between didacticism and entertainment that guides most of the creative work aimed at young people. Is the resource pack, marked for teacher and classroom use, really necessary to this play?

Perhaps instead, general discussion questions echoing those sometimes found in the back of YA novels would have been a better compromise and ultimately, more useful and accessible to the intended audience of young adults.

In an interview with the Guardian, Sabrina Mahfouz said that she wanted Noughts and Crosses to show ‘how oppressive systems can destroy and determine people’s lives from a young age. In some cases, they’re powerless, in others they’re able to take back the power and make some change, but it’s not without a huge amount of sacrifice and pain’. (4) While Noughts and Crosses was a step in this direction, it didn’t feel like it managed to get all the way there with the pacing of the character development feeling off-centre and, consequently, undermining this message. Yet, it is an optimistic start. By adapting a story as powerful as Blackman’s into a memorable piece of theatre aimed at young adults, Mahfouz’s contribution to the future of YA literature being performed on stage is commendable, even if it falls short of achieving her ambitions. As for the Noughts and Crosses novel, a BBC TV adaptation has been in the works since 2018 with the rumoured release date due to be sometime this year. (5) It will be a six-part miniseries with each episode having a running time of one hour – this should provide ample time for a more satisfying character development that is missing from the play. In the meantime, the iconic YA series will be going back on my ‘to-be-reread’ list, and if it isn’t on yours already, I highly recommend it.

- Evans, Greg. “Viral Tweet Explains Why the Colour of a Plaster Is so Important.” indy100, The Independent, 27 Apr. 2019, www.indy100.com/article/plaster-colour-skin-tone-dominique-apollon-tweet-viral-8889176., accessed 27 May 2019.; ‘Should the Colour of Plasters Match Skin Tones?’, BBC News, 26 April 2019, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/48060767, accessed 27 May 2019.

- Holyoake, Emily. ‘Review: Noughts and Crosses at Derby Theatre’, Exeunt Magazine, 8 Feb. 2019, http://exeuntmagazine.com/reviews/review-noughts-crosses-derby-theatre/, accessed 27 May 2019.

- Though the video is unlisted on YouTube, it can be found directly through this link: Pilot Theatre, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cfLWccy_55Y&feature=youtu.be, accessed 27 May 2019. There is also a link to it within the Pilot Theatre Noughts and Crosses Teaching Pack which can be found on the Pilot Theatre website: https://www.pilot-theatre.com/performance/noughts-crosses, accessed 27 May 2019.

- Akbar, Arifa. “Sabrina Mahfouz: ‘People Used to Say They Expected Me to Be a Lot More Foreign’.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Jan. 2019, www.theguardian.com/stage/2019/jan/19/sabrina-mahfouz-interview-noughts-and-crosses-emma-watson, accessed 27 May 2019.

- Carr, Flora. “When Is Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses on TV?” Radio Times, 4 Apr. 2019, www.radiotimes.com/news/2019-04-04/noughts-and-crosses/, accessed 28 May 2019.