PhD researcher Chisaki Fukushima is currently in Japan conducting fieldwork. Covid-19 has caused the nature of her fieldwork to change, which she has had to adapt to, but it has also provided an opportunity to observe other phenomena, particularly, the changing role of masks in the community.

Transformation, observation and Covid-19

It took only a couple of weeks from the beginning of March for the small rural town I have been living in for my field research to turn into a ghost town. All the stores were shut except for the supermarket and franchise convenience stores, and no one, except a few people in cars, was visible on the street.

Given a large part of my research involves human contact, methods such as face-to-face interviews and participant observation became impossible to conduct, apart from the latter, at a distance. My ‘outsider status’ has made my fieldwork further challenging; people recognise that I am from outside of the community, and, even worse, that I am from abroad, where the terrible Covid-19 crisis is taking place. Despite the fact that I have observed a quarantine period and observe scrupulous hygiene measures, people see the ‘outside’ world in me. (I am continuously reminded that my existence has multiple social layers that will impact the data I produce.) Therefore, in order to minimise my ‘alien’ attributes, I moved into my informants’ neighbourhood, which allowed me to interact with them daily and reduce the anxiety some people may have felt about me moving in and out of their space.

Material Culture: Mask Behaviour

While some elements of my fieldwork have been compromised, new opportunities have arisen. For example, I have had occasion to observe how the rural Japanese community I have been living in has adapted to the public health threat that is Covid-19. I have noticed the rise of social conformity regarding public hygiene, and mask wearing is a significant part of this.

Kinds of masks

The mask is a relatively recent development in public health, originally introduced in Japan during flu outbreaks just before World War One[1]. The masks I refer to are not face masks but ‘surgical masks’ which cover the mouth, the nostrils (depending on how they are worn) and the surrounding area, regardless of the size or fit. These come in an array of categories: unisex, men/women, adult/child, S/M/L. They are available in an astonishingly varied range of materials, brands, character designs, patterns, colours and so on. Some people opt for a utilitarian look, while others seem to want to express themselves, using their masks as a fashion statement. Both are quite commonly observed.

Mask wearing

Because of its coastal topology and a history of fishing spanning hundreds of years, the region is exposed to numerous and diverse diseases and natural disasters. People practice(d) exorcist rituals and the worship of an epidemiological god. However, wearing masks has not historically been one of their practices. Although fishing is no longer economically viable, the rituals and the storytelling around fishing are still actively practiced and maintained on a daily basis. Fishermen’s patriarchal kinship is still dominant, and status and position are inherited by men from prominent families. I do not know if fishermen’s machismo has something to do with not wearing masks, but this is a population proud of being healthy because of its high fish diet, and there are some people who seem to have actively resisted wearing masks so far.

Masks and sneezing

The common pattern when people sneeze without a mask is to cover their mouth with the palm of their hand. Coughing and clearing the throat are associated with more varied hand gestures, including covering the mouth with the hand either stretched or in a fist. Using a hand to cover one’s mouth remains common in public spaces with or without mask. However, people in the home environment tend to alternate behaviours by not using their hand at all or covering their mouths with their hand slightly further out in front of the mask.

Gendered divisions

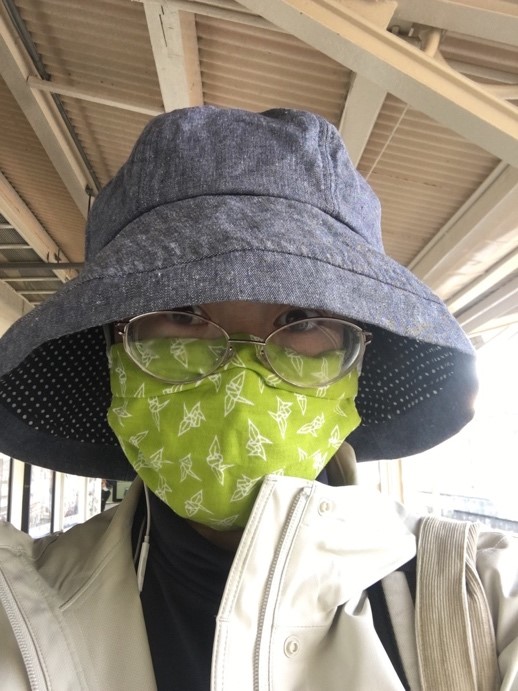

I have observed that both purchasing and crafting masks from scratch generally seems to be done by female family members, either the wife of the head of household or the wife of the older generation of the household. Machiko-san, an informant, complained, “There are no masks at the shop so I thought, I must make it rather than exposing (one/my)self to risk without wearing a mask!” She picked a couple of masks out of her beautiful batch for me. When she is praised by people, she demurs, “No, no, no, I just made use of a piece of textile that was of no use at home, handkerchiefs and towels, rather than let them go to waste. They are not authentic at all and only made up by myself (laughter).” I wear her mask every day and sometimes see the same patterns and designs worn by strangers on the street. I assume they were given by Machiko-san. Handmade masks are becoming very popular these days because people stay at home with reduced outside work, and this is something they can make at home. That is an interesting case of people’s needs matching their interests and talents in the face of the Covid-19 emergency.

Meanwhile, masks are the first thing to run out stock at stores. It is

not an exaggeration to say that the everyday discussions start and end with

masks. I clearly see the mask becoming perceived to be one of life’s

‘necessities’. The cultural connotations of this are profound, but as yet,

unknowable.

[1] Palmer, Edwina; Rice, Geoffrey W.(1992) ‘A Japanese Physician’s Response to Pandemic Influenza: Ijiro Gomibuchi and the “Spanish Flu” in Yaita-Cho, 1918-1919’. Bulletin of the History of Medicine; Baltimore, Md. Vol.66 Issue.4: 560.