Mark Shucksmith, Polly Chapman, Jayne Glass, Jane Atterton.

New research shows that many rural households already experiencing poverty and financial vulnerability in Britain will be hardest hit by increases in energy costs. The new measures announced by the Chancellor will still leave many more rural households in fuel poverty.

New research shows that many rural households already experiencing poverty and financial vulnerability in Britain will be hardest hit by increases in energy costs. The new measures announced by the Chancellor will still leave many more rural households in fuel poverty.

While rural areas are often imagined to be less prone to poverty, research by the Financial Conduct Authority [i] showed that 54% of rural dwellers were financially vulnerable in 2018, and analysis [ii] of the British Household Panel Survey found that in the two decades before the financial crisis 50% of households in rural Britain experienced poverty at some point.

Our 2021 Rural Lives [iii] study explored hidden poverty and financial vulnerability in rural Britain more deeply, finding that many rural dwellers face fuel poverty [iv], higher costs of living, insecure employment and lack of access to services as these are centralised and digitalized. The state’s welfare systems are poorly adapted to rural circumstances, with lower rates of benefit take-up and additional obstacles to those in towns.

Fuel poverty is particularly prevalent in rural areas because many properties are not connected to mains gas, therefore having to rely on more expensive and less regulated sources such as oil and LPG or less efficient electric heating systems. Houses tend to be older and poorly insulated, and difficult and costly to retrofit with insulation [v]. Furthermore, poor households in rural areas are more likely to live in private rented houses, than in urban areas where social housing is more available. On top of this, rural households incur higher transport costs in travelling to access services and employment, often with no public transport available. A recent report by the Scottish Government [vi] notes that a third of households in remote rural areas were in extreme fuel poverty [vii] in 2019 compared to 11% of households in the rest of Scotland.

Now high rates of inflation are anticipated by the Office for Budget Responsibility, and it is predicted that increases in energy costs and rising inflation will hit rural areas hardest, with 57% of households in the Western Isles and 47% in the Highlands of Scotland experiencing fuel poverty, according to modelling by Energy Action Scotland [viii]. In England, about a third of households are predicted to experience fuel poverty in rural West Norfolk, Northeast Lincolnshire, Herefordshire and Shropshire, as well as in the Chancellor’s own constituency of Richmondshire [ix].

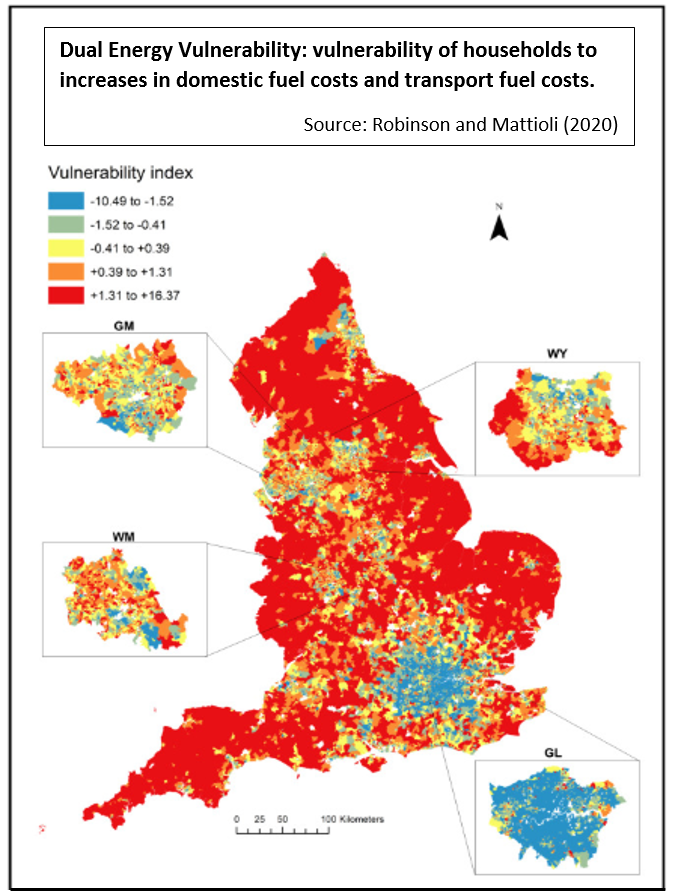

A comprehensive study by Robinson and Mattioli [x] has recently estimated and mapped the potential vulnerability of households in Britain to the combination of increased domestic energy costs and rising petrol prices. Their results for England in the map (below) show that it is rural households which exhibit the greatest ‘dual energy vulnerability’ and are therefore likely to suffer the greatest financial pressure in the months ahead.

The interviews conducted as part of the Rural Lives study reveal the human impact of fuel poverty in rural Britain. One person told us how he had not realised that his retired parents were suffering fuel poverty until he visited them unexpectedly one day and found them sitting in the cold with their coats on and duvets over them – he discovered then that they could only afford to switch the heating on when he was due to visit.

Another Perthshire resident told us how they kept the central heating switched off because of the expense, relying instead on collecting free firewood for a wood-burning stove. In Northumberland, we learned how some households run out of oil early in the winter and cannot afford to buy more. Despite these challenges, it was encouraging to learn about several organisations/initiatives working on this issue in each place we studied.

Addressing the cost of living crisis and rising fuel poverty facing so many rural households requires action on many levels. Most immediately it requires benefit levels to rise in line with inflation and for initiatives to promote take-up in rural areas by those who are eligible. Energy-related initiatives such as home insulation, help with the costs of oil-buying and energy efficiency measures and advice should be expanded, building on the success of existing local schemes. These could be assisted by grants for the installation of more energy-efficient heating systems for those in most need and by rural-proofing and island-proofing of new regulations which threaten the viability of rural insulation schemes [xi].

For the medium-term, encouragement for the generation of renewable energy in rural areas could be given by restoring the incentives withdrawn by the UK Government in recent years, investing in the infrastructure necessary to feed increased power into the grid, and enabling residents of these areas to benefit from the cheaper energy produced there. As one islander put it [xii], “the electricity grid was built on a system of power generation near major cities which branched out to supply peripheries. That system now needs to be reversed so that the peripheries can feed renewable energy back to the urban centres.”

Authors

- Mark Shucksmith OBE is Professor of Planning and a CRE Associate at Newcastle University. Polly Chapman is CEO of HISEZ CIC, Inverness.

- Polly Chapman is CEO of HISEZ CIC, Inverness.

- Jayne Glass is a Research Fellow in the Rural Policy Centre at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC).

- Jane Atterton manages theRural Policy Centre at SRUC (Scotland’s Rural College).

References

[i] Financial Conduct Authority (2018) ‘The Financial Lives of Consumers across the UK’, Financial Conduct Authority report.

[ii] Vera-Toscano, Shucksmith and Brown (2020) ‘Poverty Dynamics in Rural Britain 1991-2008: Did Labour’s Social Policy Reforms Make a Difference?’, Journal of Rural Studies, 75: 216-228.

[iii] Shucksmith, Chapman, Glass and Atterton (2021) Rural Lives: understanding financial hardship and vulnerability in rural areas. www.rurallives.co.uk

Shucksmith, Glass, Chapman and Atterton (2023) Rural Poverty Now: Experiences of Social Exclusion in Rural Britain, Policy Press, Bristol (in press).

[iv] Fuel poverty is defined as spending more than 10% of household income on energy, after housing costs have been deducted.

[v] https://tighean.co.uk/statement-from-tighean-innse-gall-tig-2nd-of-march-2022/

[vi] Scottish Government (2021) ‘Poverty in rural Scotland: a review of evidence’, Scottish Government report.

[vii] Extreme fuel poverty is defined as spending more than 20% of household income on energy, after housing costs have been deducted.

[viii] Energy Action Scotland (2022) https://www.eas.org.uk/en/fuel-poverty-set-to-break-the-50-barrier-in-parts-of-scotland_59652/

[ix] End Fuel Poverty Coalition (2022) https://www.endfuelpoverty.org.uk/revealed-the-streets-where-nearly-everyone-is-in-fuel-poverty/ See also: https://acre.org.uk/fuel-poverty-on-the-increase-in-rural-areas/

[x] Robinson C and Mattioli G (2021) Double energy vulnerability: Spatial intersections of domestic and transport energy poverty in England, Journal of Energy Research and Social Science, 70,

[xi] https://tighean.co.uk/statement-from-tighean-innse-gall-tig-2nd-of-march-2022/

[xii] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/feb/12/renewable-energy-wind-changed-fortunes-lewis-islanders