Continuing with research into the alcohol market conducted at Newcastle University, Emeritus Professor Christopher Ritson discusses how it is important to get your market research right.

Background

Over a 15 year period between the early 1980s to late 1990s I did a series of studies for the Government of Cyprus concerned with agricultural aspects of the country’s application to join the (then) European Community. The first was an overview of the implications of having to adopt the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This was followed by four commodity-specific studies covering milk and dairy products, fruit and vegetables, cereals, and wine. This blog reports on a spin-off of the wine study, involving a market research project in which all second year students on the then Food Marketing degree participated.

Pitfalls in Generic Advertising

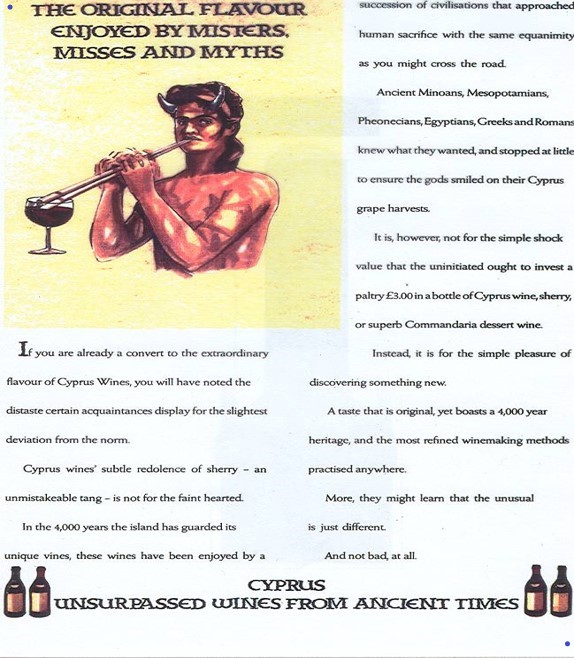

Adopting the CAP for wine required radical change to the Cyprus wine policy, in which large numbers of small grape growers sold their produce to the four wine “factories” at prices fixed by the Government. By chance, when working on this, I happened to be in Nicosia when a London advertising agency presented their proposal for a campaign for Cyprus wines marketed in the UK, sponsored by the Cyprus Trade Ministry. Previously, this had involved little more than pictures of large numbers of wine bottles on a table- and (as often with generic advertising) the companies involved were more interested in how prominently their brands featured in the picture, rather than how effective the advert was likely to be. Here is one of the proposed new adverts shown at the meeting.

Reading this commentary it is not difficult to appreciate why the Trade Ministry officials and representatives on the wine companies were unimpressed by what they saw. The Agency had obviously decided that they would not promote Cyprus wines in terms of traditional wine quality variables, directed at existing UK wine consumers. Rather the idea was to attempt to attract a new younger clientele and to make a virtue of Cyprus wine’s “rather different” quality characteristics: “Deviation from the norm”; “subtle redolence”; “not for the fainthearted”; “shock value”; “the unusual is just different”; “not bad at all”. This was in stark contrast to the view in Cyprus that their “classic“ wines were well-known and possessed traditional wine quality attributes. There was, however, an even more heinous crime in the proposal from the advertising agency.

The Wrong Gods

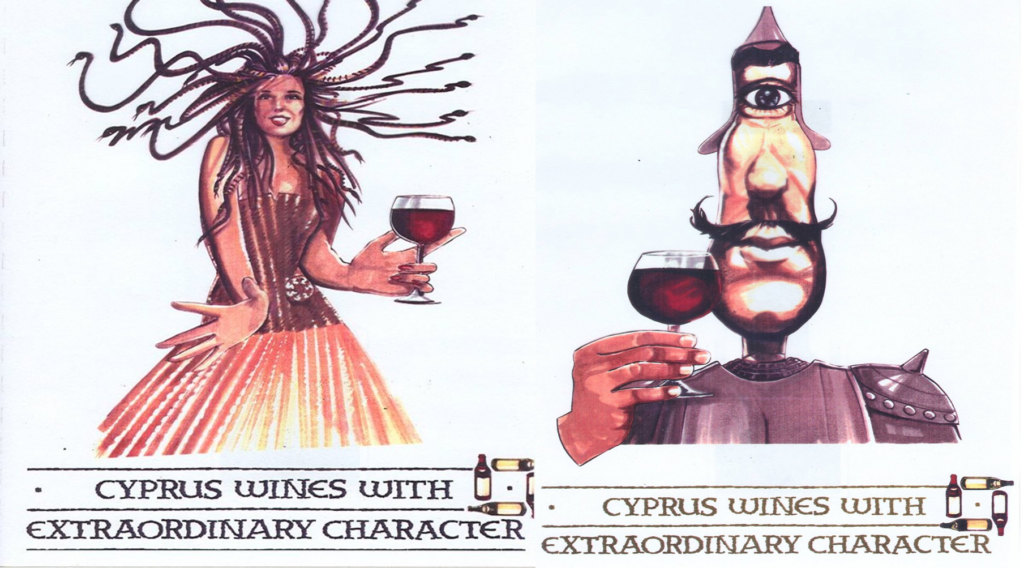

Here are two more of the proposed adverts.

Virtually all the wines in Cyprus in the 1980s were produced by one of four companies with no vintage years on labels, and brand names either taken from aspects of Greek mythology associated with Cyprus (e.g. “Aphrodite”; “Arsinoe”; “Thisbe”) or with the island’s historic culture (e.g. “Saint Panteleimon”; “Othello”; “Bellapais”). Anyone who has visited Cyprus will be familiar with some of these names; and if you attended any of the graduation dinners which used to be held at the Old Assembly Rooms you will recognize Othello and Aphrodite. These were the house red and white wines, a consequence of the national loyalty of the owner, Homer Michaelides.

As such, the pictures of Pan, Cyclops and Medusa featured in the proposed adverts caused outrage: “These are not our gods – they are Greek gods.” So this clashed with the requirement that the image of the wines needed to reflect the culture and history of the Island – simply being from Greek mythology was not enough. The representatives of the London Agency were told to go away and have another try.

The perils of market research

At the time, the degree programme in Agricultural and Food Marketing included a second year market research module in which all the students participated in a group project. I negotiated a small grant from the Cyprus Government to fund a survey of UK consumer knowledge and attitudes to wine from Cyprus. With about 50 students each completing 10 questionnaires among “friends and family” a good sized sample was obtained and although, of course, a “convenience sample”, nevertheless probably reasonably representative of the UK wine drinking public.

The questionnaire addressed three issues: 1) How did consumers rate wine form Cyprus compared to other wine producing countries in the Eastern Mediterranean; 2) whether consumers would value adding vintages, grape variety, and specific areas (estates) to wine labels; and 3) how familiar wine consumers were with the existing brand names. For the latter, I invented two fictitious wine brands – one a Greek God (Apollo), the other the name of a hotel in Athens (Esperion) to go alongside six existing brands. The question was “Have you i) heard of this wine; ii) ever drunk it?

Well, maybe you have guessed by now. More participants had heard of the two fictitious Cyprus wine brands than two of the real ones; and some people had even drunk them!

But this served a very useful purpose – to correct the mistaken belief within Cyprus that their wines were well-known in the UK market, as a spur for a new marketing campaign.

“Classic Stuff”

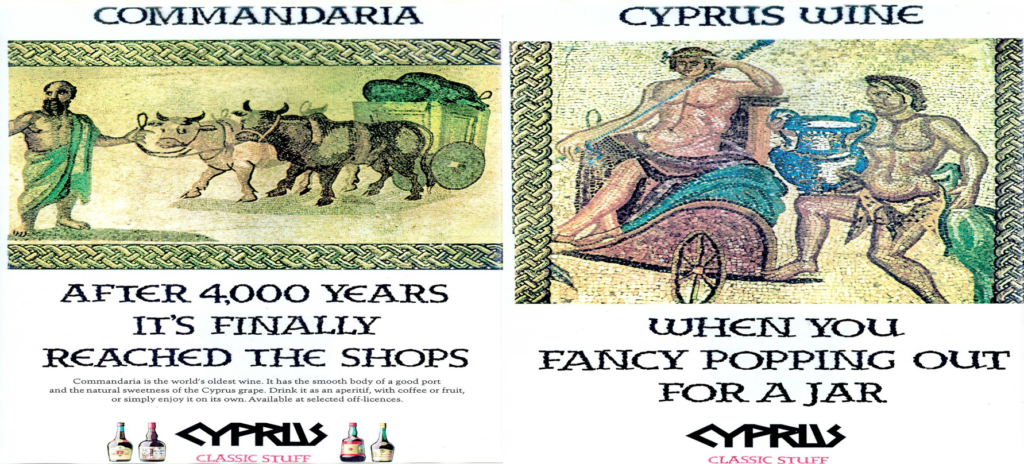

The London advertising agency had another try. Here are two examples of the new posters (which did subsequently appear at London Tube stations).

The Agency has clearly now done its homework on the cultural history of Cyprus. There is still the jokey image, and the decision to concentrate on younger new wine drinkers has been retained, but the images are from the famous Paphos mosaics.

Postscript

There is now a number of small independent wineries in Cyprus, the best known based at a Monastery. These have adopted “estate bottled” and “vintages” in competition with the branded products of the large wine companies, which have in turn introduced new products to emulate them. A few years after the events described above, I was invited to lunch with the elderly owner of the Amathus hotel in Limassol together with the Chairman and Oenologist from the largest of the traditional wine companies. Naturally, they ordered a bottle of wine from their company and I noticed that the familiar brand now had a vintage year cited on the label. Being conversational I said “I see this is 1990”. The Oenologist did a bit of stiffing and sipping and then replied, no – think this is 1991. “But, I said it says 1990 here”. Ah, yes, he replied, but these labels are expensive to produce so we only change them every other year.”