Professor James Law & Mr Tom King

James Law is Professor of Speech & Language Sciences, and Tom King is Statistician, both based in the School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences. This blog article highlights how Save the Children commissioned James and Tom to do some analyses of the Millennium Cohort Study. The paper they produced now features extensively in a new report published earlier this month, entitled: Read On. Get On: How Reading Can Help Children Escape Poverty (PDF: 1.46MB), which has been extensively reported in UK media stories.

In the run up to the General Election lobby groups press hard to have their interests represented in the party manifestoes. With the 2015 General Election looming now is the time to line up the arguments and write the documents that will inform this process.

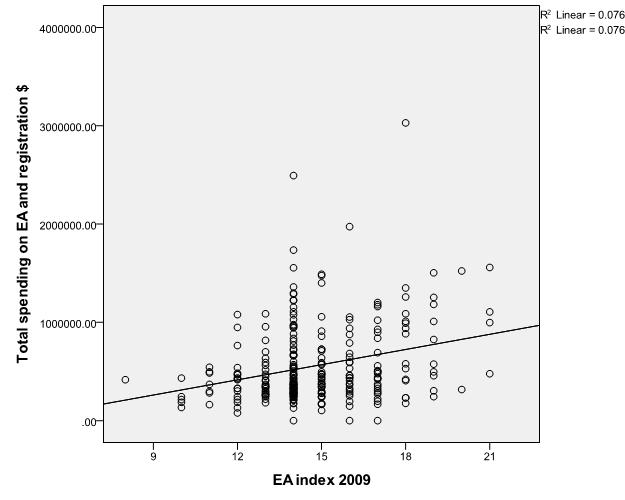

Save the Children, together with a number of different charities, are writing a document entitled “Reading for a Fairer Future: A National Mission to Ensure All Children are Reading Well by 11 by 2025: delivering the Read On. Get On. campaign”. This draws together data from a variety of sources to make the case that parties need to be focusing on the attainment (and specifically oral language and literacy) of very young children in the early years if they are to get a grip on key policy issues flagged up by the UK’s performance in the Programme for International Assessment (PISA) and other international league tables. Reading attainment amongst 10 year olds is more unequal in England than in all other countries in Europe, with the single exception of Romania. In part this an issue about the achievement of all children but Save the Children were particularly interested in the differences between children who are relatively socially advantaged and those that are not. As part of this process Save the Children commissioned Professor James Law together with SLS statistician Tom King to carry out some analyses of the UK’s Millennium Cohort Study of 18,000 children born in 2000 and assessed at regular intervals since then.

What happens beyond the school gates and in homes is critical. Our work for this report shows that reading to and with children matters for both mothers and fathers, but the impact of father’s reading – particularly to children after they have started school – appears even greater. Children whose fathers read with them less than once a week at the age of five had, by the time they were seven, a reading level half a year behind those who had been read to daily.

There is also a wide ‘book gap’ in England: almost a quarter of 11 year olds in the poorest families had fewer than 10 books in the home, which contrasts with under 4 per cent of those in the richest families. This is likely to reflect a wider attitude and approach to reading in the home: children in homes with more than 500 books are on average more than two years ahead of those growing up in households with fewer than ten books.

The ‘Read On. Get On’ report concludes “Achieving this goal would mean that every single child born this year would be able to read well by the time they finish primary school in 11 years’ time. In order to ensure we are making progress, we are also setting two interim goals. Because the early years of a child’s life are so critical and because early language development is the building block on which later reading develops, we are setting the 2020 goal of: all children achieving good early language development by the age of five by 2020. And because we need to ensure that we are on track for achieving the ultimate 2025 goal, our second interim goal will be: to be at least halfway to achieving the 2025 goal for 11-year olds by 2020” (page vii). Ambitious goals indeed, but we will only know whether they have been met if we have access to good quality national data. The next step will be the manifestoes and the response from the different political parties.

Please note:

The paper based on Newcastle University’s research is cited on pages vii,6,33-35,40, 42-43 and the whole of Chapter 2 of the Read On. Get On. Report (PDF: 1.46MB). See also Newcastle University’s press release.

The Read On. Get On. report and/or the Newcastle University research is referred to in media stories in: The Guardian, The Independent, The Telegraph, The Sun, The Times Online, ITV, to name just a few.

For more information about the Read On. Get On. campaign, see their website.