In the latest of our series focussing on the Early Career Researchers (ECRs) in ICaMB, we feature Dr Heath Murray. After completing undergraduate studies at the University of California, Los Angeles and then obtaining his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Heath came to the UK to join the lab of Prof Jeff Errington in Oxford. From there he re-located to ICaMB, and in 2009 was awarded a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. Here, Heath describes his research into the mechanisms of DNA replication, and explains why he became interested in this field.

In the latest of our series focussing on the Early Career Researchers (ECRs) in ICaMB, we feature Dr Heath Murray. After completing undergraduate studies at the University of California, Los Angeles and then obtaining his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Heath came to the UK to join the lab of Prof Jeff Errington in Oxford. From there he re-located to ICaMB, and in 2009 was awarded a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. Here, Heath describes his research into the mechanisms of DNA replication, and explains why he became interested in this field.

By Dr Heath Murray

Hello, my name is Heath Murray and I’m a Royal Society University Research Fellow in ICaMB’s Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology (CBCB) studying DNA replication. DNA is one of the most important molecules required for life because it encodes the information, or the blueprint, used to build a cell (i.e. the most basic unit of an organism). In order for a cell to create new cells it must synthesize an exact copy of its DNA, an extraordinary process when you consider that the genomes of most cells contain millions of individual DNA subunits!

Bacillus subtilis is a useful model system as it proliferates rapidly and is amenable to genetic, cell biological, biochemical, and structural analyses

Bacteria are ideal model systems to study this fundamental process because they are much less complex than human cells (e.g. all of their DNA is encoded by a single chromosome, whereas humans have 23), and this allows us to understand how they work at the greatest possible level of detail.

I was introduced to bacteria when I was an undergraduate student and the effect was transformative. My mentors taught me how to add a specific gene (a DNA sequence) to a bacterial cell, and if it worked properly then the bacteria would turn blue!

That basic genetic experiment was one of the coolest things I had ever done, and from that point on I worked hard to learn the trade of “bacterial genetics”.

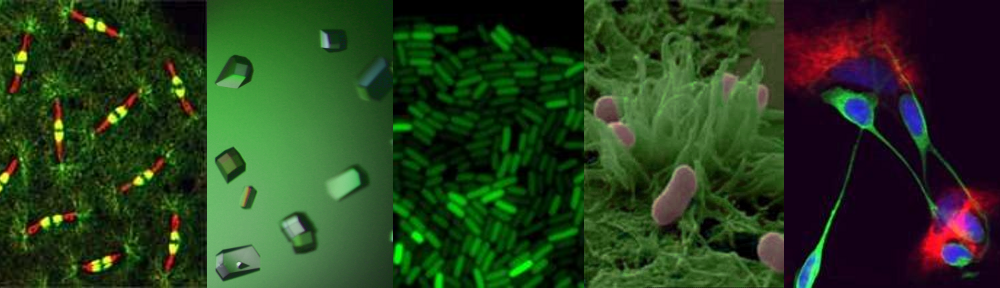

Today my research group focuses on understanding how DNA replication is controlled so that each new cell will end up containing an exact copy of the genetic material from its predecessor. We employ a wide range of complementary experimental techniques: genetic engineering of bacterial strains, biochemical analysis of purified proteins, and fluorescence microscopy.

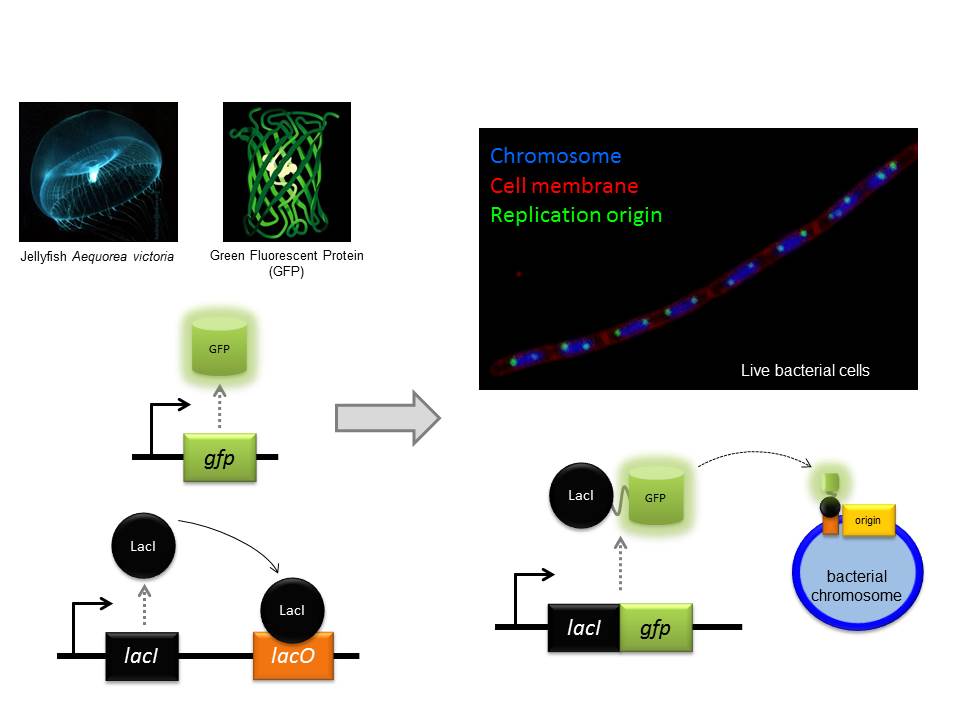

Fluorescence microscopy is a particular strength of the CBCB because there are several bespoke systems specifically designed for bacterial cells (bacteria are 10-100 times smaller than most human cells). One of the core approaches we use is to genetically engineer a protein we want to study so that it will be fused to a special reporter protein called GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein, originally isolated from jellyfish!) within the cell. Using this approach we can then visualize where our test protein is because it fluoresces when exposed to a specific wavelength of light. Some of our microscopes are so sophisticated that we can observe the location of single proteins and track their movements within living cells.

One of the approaches we often use is to visualize specific regions of the genome within living cells. First, a specific DNA binding protein ( called “LacI”) is genetically fused to GFP. Second, the DNA sequence recognized by LacI (called “lacO”) can be genetically integrated into any location of the genome. Since I study DNA replication, I am particularly interested in the site of the bacterial chromosome where DNA synthesis is initiated (called the “replication origin”). Third, fluorescent dyes are added to cells that bind to the cell membrane and the DNA. Finally, we utilize our fluorescent microscopes to visualize the location of replication origins within individual cells. In the image shown, the live bacterial cells contain chromosomes that are in the process of being replicated, and therefore they have duplicated and separated their replication origins!! This image also emphasizes the fact that although bacteria lack the organelles found in eukaryotic cells, they are nonetheless highly organized (notice how the replication origins are characteristically located at the outer edge of each chromosome).

The GFP protein from jellyfish can be used to fluorescently tag proteins in vivo. Fluorescence microscopy can then be used to localise the tagged protein within the bacterial cell.

Well that’s it for my first ICaMB blog! I hope you enjoyed hearing about how I became interested in bacterial genetics and about my work on bacterial DNA replication. Please feel welcome to contact me if you have any questions or if you would like further information regarding my research.

Links

Royal Society URF http://royalsociety.org/grants/schemes/university-research/

Centre for Bacterial Cell Biology (CBCB) http://www.ncl.ac.uk/cbcb/

Great overview of your academic experience. I look forward to reading your new posts. Maybe link to a wiki?