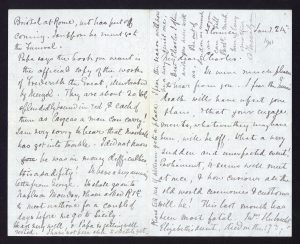

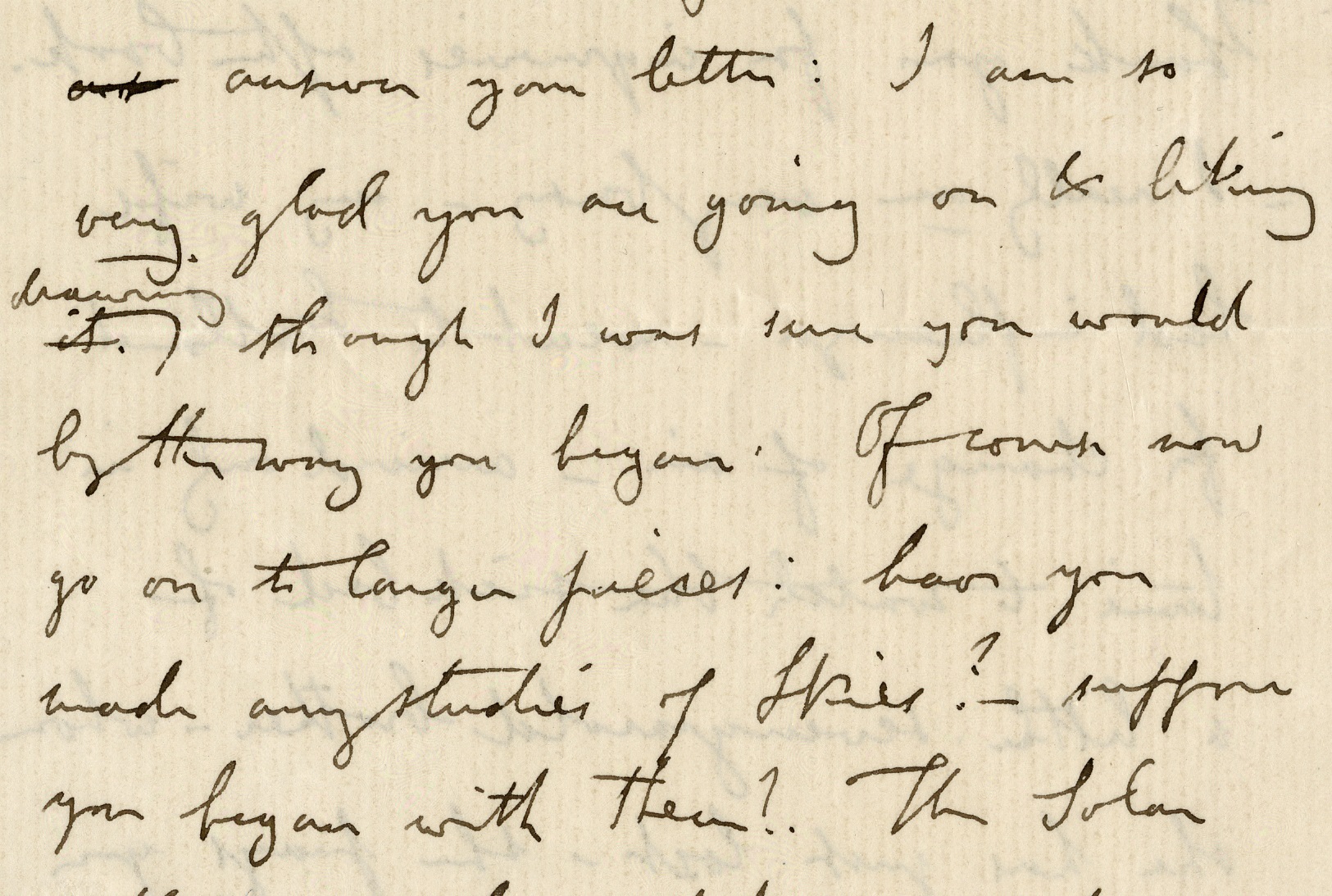

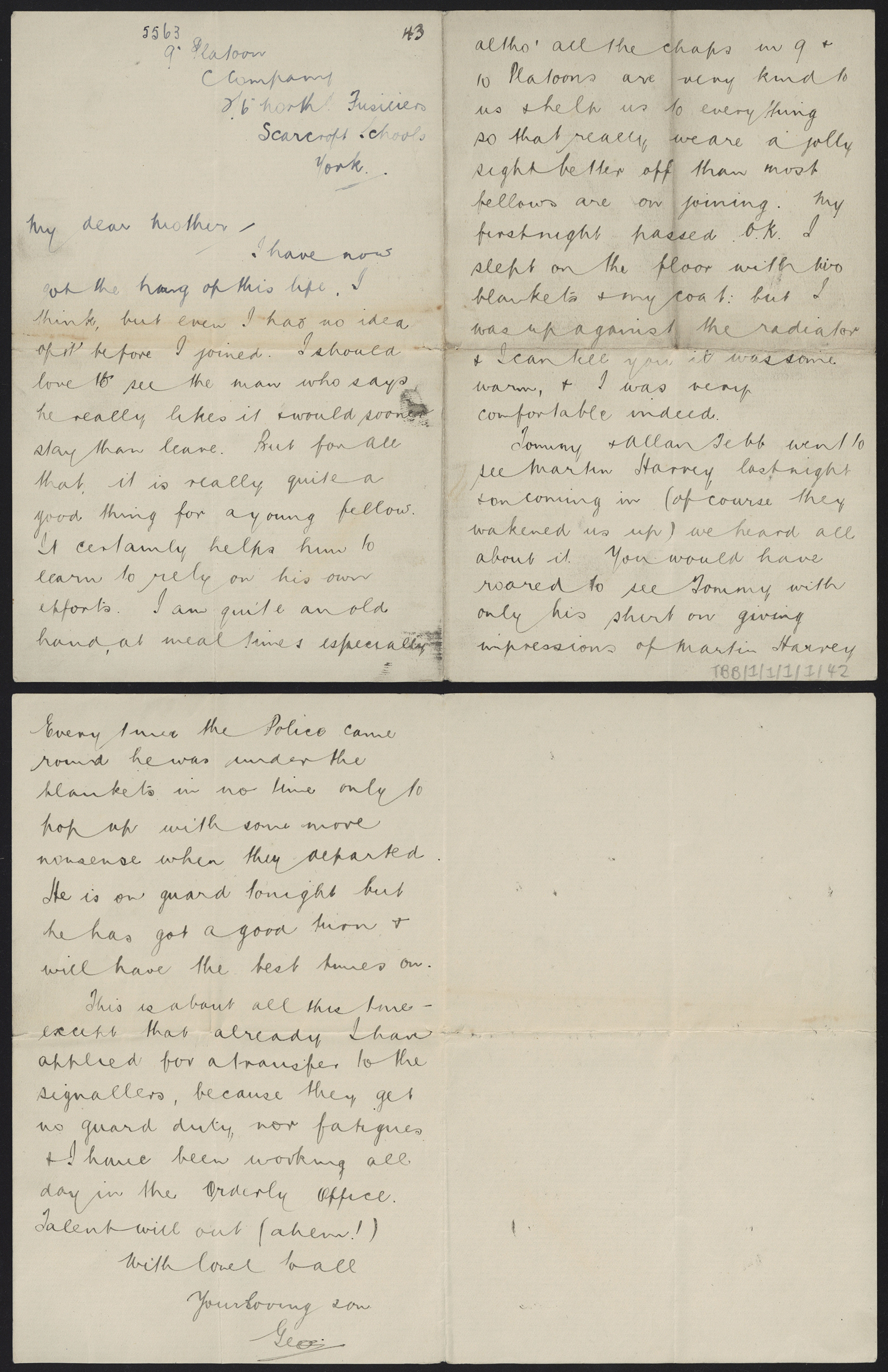

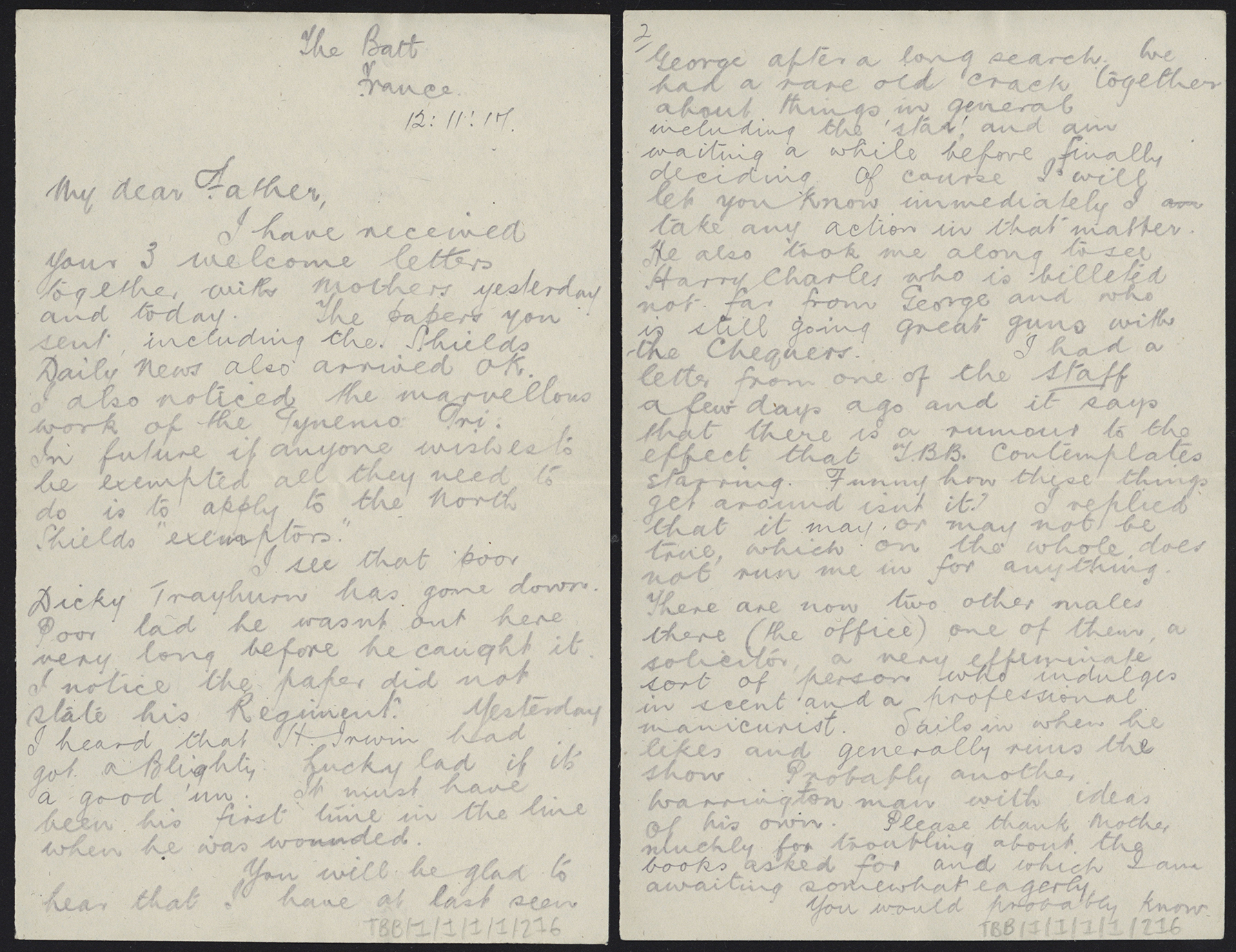

Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives holds over 1,800 letters written by Gertrude Bell to her family. One in particular was written on the 12th January 1920, where Gertrude Bell writes to her stepmother describing her concerns about the delicate political situation in the Middle East, her hopes for resolution and how she seeks to contribute. Through this and her other writing she demonstrates a depth of knowledge and involvement which contributes significantly to our understanding of early 20th Century politics in the region.

Gertrude’s journey to becoming an important figure in Middle Eastern politics began when she was born into a wealthy family at Washington New Hall in 1868 where she also spent her childhood. After studying at and graduating from Oxford University she was able to travel widely in the first years of the 20th century and developed a deep interest in the Arab region and people. Her knowledge of the region led to her being involved with the British Intelligence Service during the First World War and by 1920 she had been appointed as Oriental Secretary to the British High Commission in Iraq.

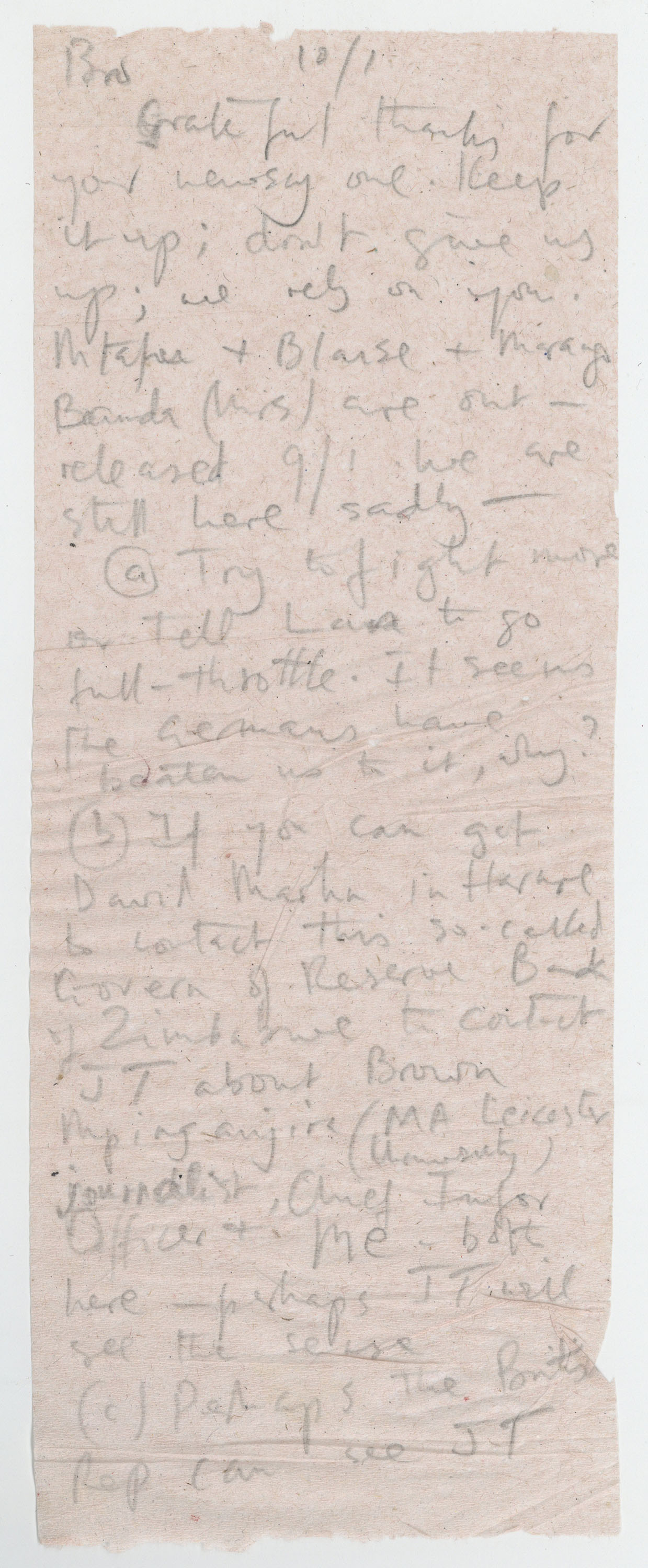

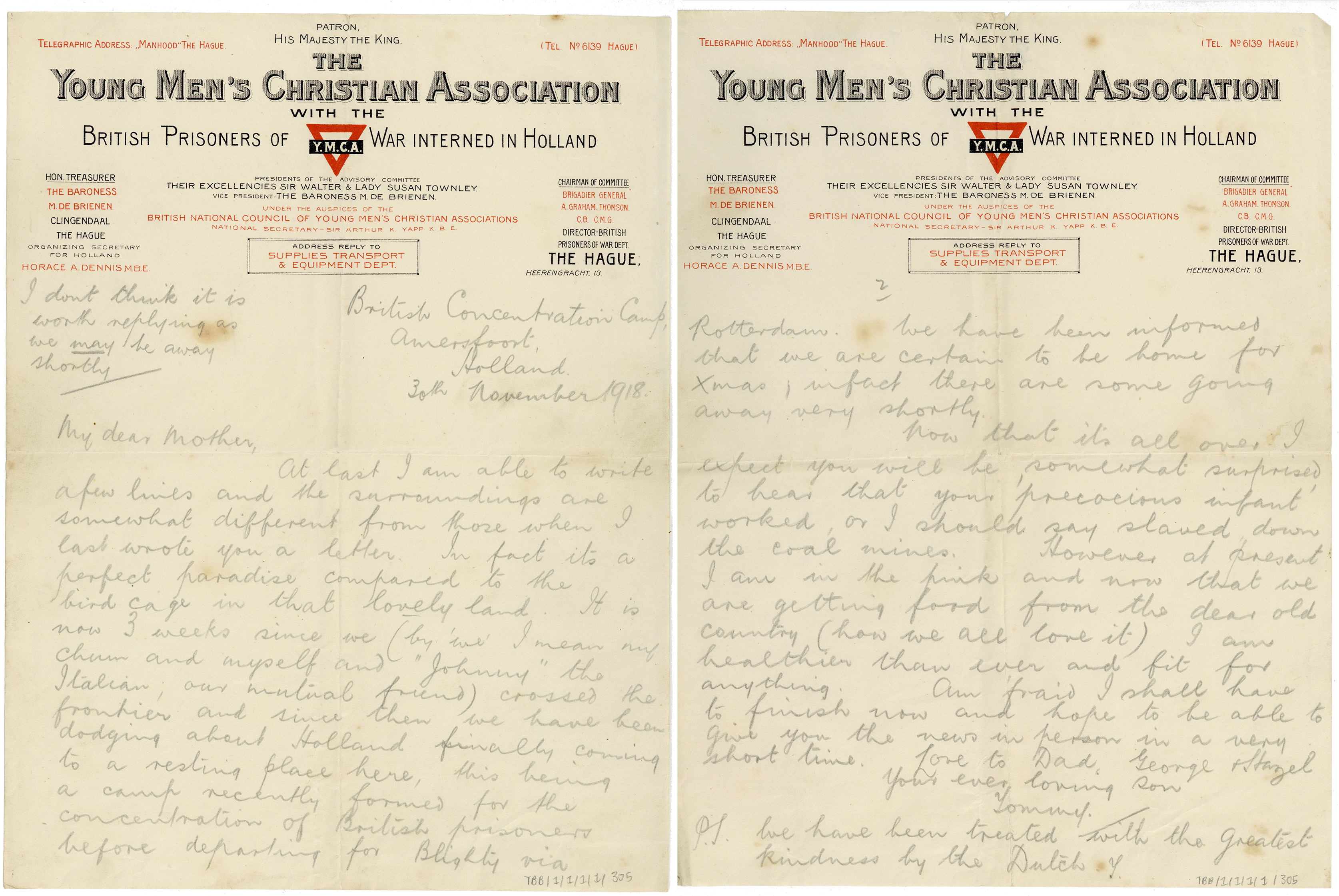

Throughout her time in the Middle East she regularly corresponded with her family in Britain, updating them on her life, travels, and thoughts about her work and the political situation in the Middle East. She wrote one such letter on the 12th of January 1920 to her stepmother, Florence Bell.

A transcript of part of this letter is below:

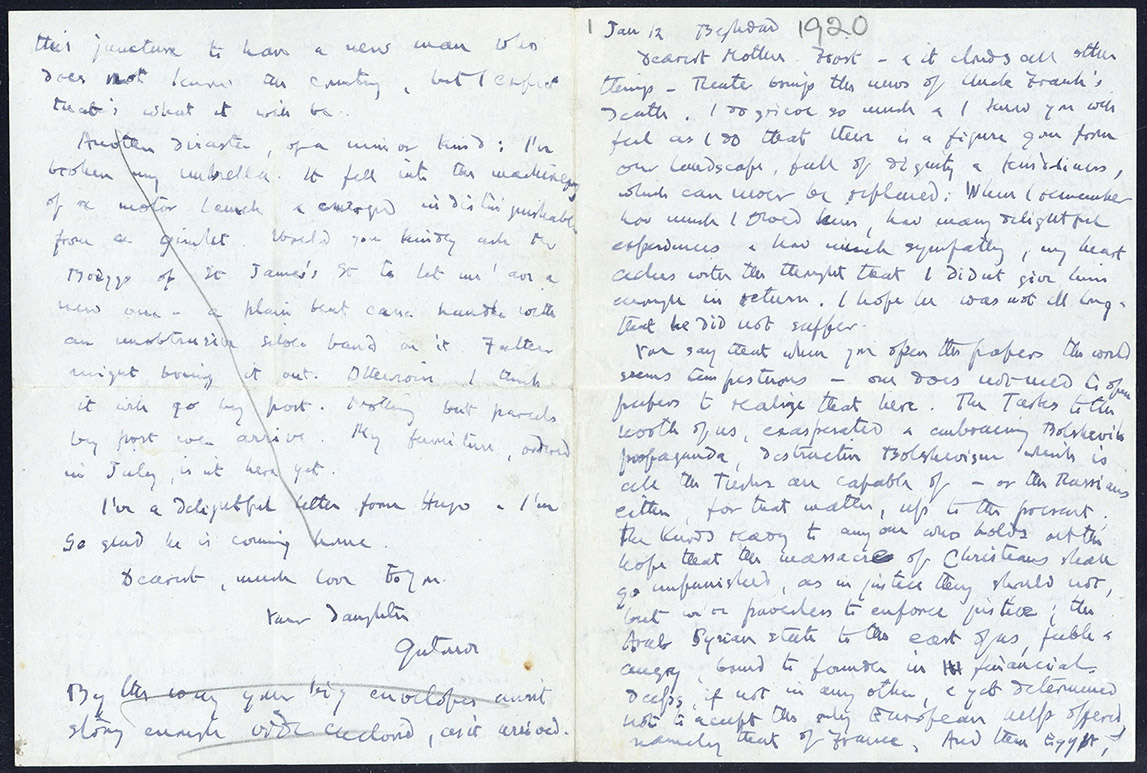

“You say that when you open the papers the world seems tempestuous – one does not need to open the papers to realize that here. The Turks to the north of us, exasperated and embracing Bolshevik propaganda, destructive Bolshevism which is all the Turks are capable of – or the Russians either, for that matter, up to the present; the Kurds ready to anyone who holds out the hope that the massacres of Christians shall go unpunished, as in justice they should not, but we’re powerless to enforce justice; the Arab Syrian state to the east of us, feeble and angry, bound to founder in financial deeps, if not in any other, and yet determined not to accept the only European help offered, namely that of France. And then Egypt, turned into a second Ireland largely by our own stupidity; and this country, which way will it go with all these agents of unrest to tempt it? I pray that the people at home may be rightly guided and realize that the only chance here is to recognize political ambitions from the first, not to try to squeeze the Arabs into our mould and have our hands forced in a year – who knows? perhaps less, the world is moving so fast – with the result that the chaos to north and east overwhelms Mesopotamia also. I wish I carried more weight. I’ve written to Edwin and this week I’m writing to Sir A. Hirtzel. But the truth is I’m in a minority of one in the Mesopotamian political service – or nearly – and yet I’m so sure I’m right that I would go to the stake for it – or perhaps just a little less painful form of testimony if they wish for it! But they must see, they must know at home. They can’t be so blind as not to read such gigantic writing on the wall as the world at large is sitting before their eyes.“

Well there! I rather wish I were at Paris this week.

“I’ve telegraphed to Father saying I hope he’ll come. I would love to show him my world here and I know if he saw if he would understand why I can’t come back to England this year. If they will keep me, I must stay. I can do something, even if it is very little to preach wisdom and restraint among the young Baghdadis whose chief fault is that they are ready to take on the creation of the world tomorrow without winking and don’t realize for a moment that even the creator himself made a poor job of it.

I’ll go to Blanche for a month or 6 weeks in the middle of the summer.

We have no news yet who our new G.O.C. in C. is to be. It’s rather a disaster at this juncture to have a new man who does not know the country, but I expect that’s what it will be.

In this letter she describes the political situation in the region, her concerns and hopes about how the British Government might seek to resolve the situation and details how she hopes to play a part in setting the future direction for the Middle East.

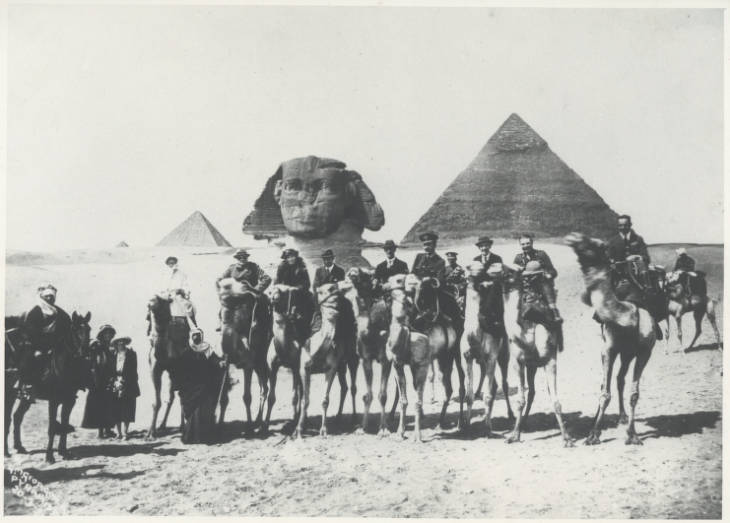

The following year she was present at the conference held at the Semiramis Hotel in Cairo in March 1921 alongside others including T.E. Lawrence and Winston Churchill. Here, the British Government met to discuss the future political shape of the Arab region and it was decided that the choice that Gertrude advocated, Faisal I bin Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi, would become the first king of the newly formed Kingdom of Iraq. The events of the Cairo Conference are also documented in the letters she sent to her family in Britain and are part of the archive.

The Gertrude Bell Archive is one of the most important and widely accessed within Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections and Archives. It contains over 1,800 letters, 8,000 photographs, diaries and other papers including lecture notes, reports and newspaper cuttings. Together they document her life and travels and form an important record of the archaeology, culture and political landscape of the Middle East in the early decades of the 20th Century. The archive has been recognised for its significance, including the insight it gives into political developments in the Middle East and the formation of Iraq in 1921, through its inclusion on UNESCO’s International Memory of the World Register (a press release regarding UNESCO’s recognition of the archive in 2017 can be found here).

Most of her letters have been fully transcribed and can be browsed and searched on our dedicated Gertrude Bell website. Additionally the photographs she took can also be seen on the website. These photographs, digitised in the 1990s, document many of the archaeological sites that particularly interested her, as well as the people and places she encountered on her earlier travels.

As the photographs are now over 100 years old, and the historic negatives are now unstable and fragile, a project is currently underway to re-digitise the collection to bring it up to current day standards, revealing hitherto unseen detail, and preserving the photographs for future generations.