Dr Zoya Pourmirza and Dr Hamid Hosseini talk about their recent work as part of a team of energy experts from Newcastle University helping UK Research & Innovation with an analysis of the UK’s existing research landscape and future infrastructure requirements.

About the authors

Dr Zoya Pourmirza is a Research Associate in Newcastle University’s School of Engineering. She is involved in a number of research and teaching projects. Her principle research interests are in smart energy systems and information and communication technology (ICT) with particular emphasis on making the ICT infrastructure energy aware and cyber secure.

Contact details: zoya.pourmirza@ncl.ac.uk

Profile details

Dr Hamid Hosseini is a Research Associate in Newcastle University’s School of engineering. His principle research interest is in the simulation and analysis of energy system. In his work for the EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration (CESI), Hamid has been investigating the planning, optimisation and operation analysis of integrated energy networks.

Contact details: hamid.hosseini@ncl.ac.uk

Profile details

UK Research & Innovation (UKRI) has recently published two reports giving an analysis of the UK’s existing research landscape and identifying its future infrastructure requirements. These reports make recommendations across six broad research sectors key to ensuring the UK remains a global leader. These six research sectors are Biological Sciences, Health and Food; Physical Sciences and Engineering; Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities; Environmental Sciences; Computational and e-infrastructure and Energy.

As members of a multi-disciplinary team of EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration (CESI) academics and researchers from Newcastle University, we were commissioned by UKRI to consult with the energy community. The team, led by CESI’s Director, Professor Phil Taylor, worked with UKRI to draft reports detailing our findings and recommendations. In carrying out this work, we made a substantial contribution to the preparation of the energy sections of the UKRI Research Landscape and Research Infrastructure reports.

Consultation exercise

The consultation exercise had three main aims: to inform future research and innovation infrastructure priorities, to provide the groundwork to ensure the UK remains a global leader in research and innovation and to set out the essential infrastructure needed to reach this long-term vision.

The team consulted extensively with leading UK energy industry and academics with expertise across a wide range of sectors, including nuclear, renewables, hydrogen, conventional technologies and whole energy systems. The consultation process was also extensive, including two questionnaires, four facilitated workshops at different locations across the UK and over one hundred 1-1 interviews with experts.

Initial analysis and findings

Based on the feedback received in the first stage of the consultation process, we drafted an interim report to UKRI giving an initial analysis of the UK Energy research infrastructure and a description of the existing energy research landscape. This interim report was included as a chapter in the UKRI Infrastructure Roadmap report alongside chapters for each of other five key research sectors.

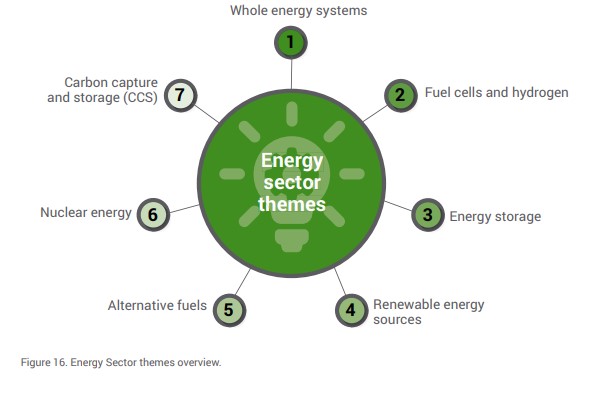

An important finding of our initial consultation exercise was that opportunities to grow future energy research and innovation infrastructure could be classified in seven key themes. These informed further rounds of consultation, and are listed in the UKRI initial analysis report as follows:

- Whole energy systems, including energy demand and power distribution networks

- Fuel cells and hydrogen

- Energy storage

- Renewable energy sources

- Alternative fuels

- Nuclear energy – fission and fusion

- Carbon capture and storage

Final reports

Following this second consultation exercise, we incorporated our findings into two detailed reports for UKRI on the existing energy research and innovation landscape and on the sector’s future infrastructure requirements. These formed the basis of the Energy sections in the two recently published UKRI reports:

- The UK’s research and innovation infrastructure: Landscape Analysis

- The UK’s research and innovation infrastructure: Opportunities to grow our capacity

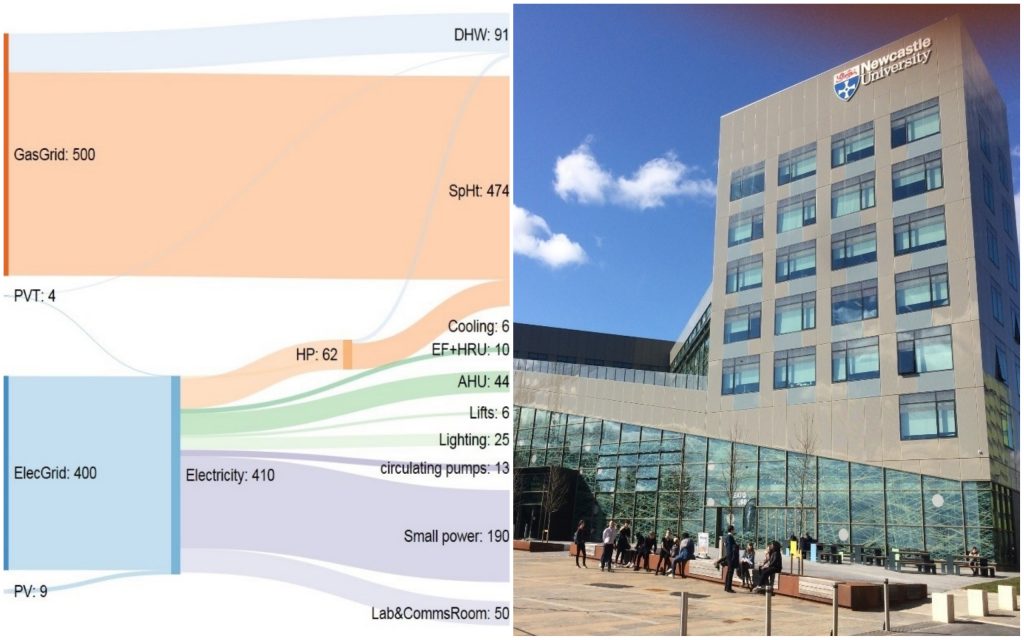

These reports referenced key energy research undertaken across the UK, including research involving multi-disciplinary teams from Newcastle University such as CESI and the Active Building Centre (ABC).

Key findings and recommendations

As a result of the consultation exercise, we helped to develop a snapshot view of existing infrastructure of regional, national and international importance. We identified thirty-three dedicated energy infrastructures and help to write case studies of existing key energy research infrastructure which were published in the Landscape Analysis report.

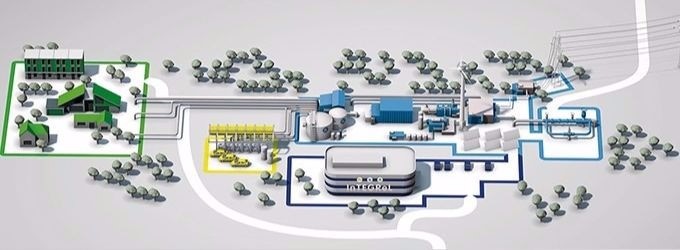

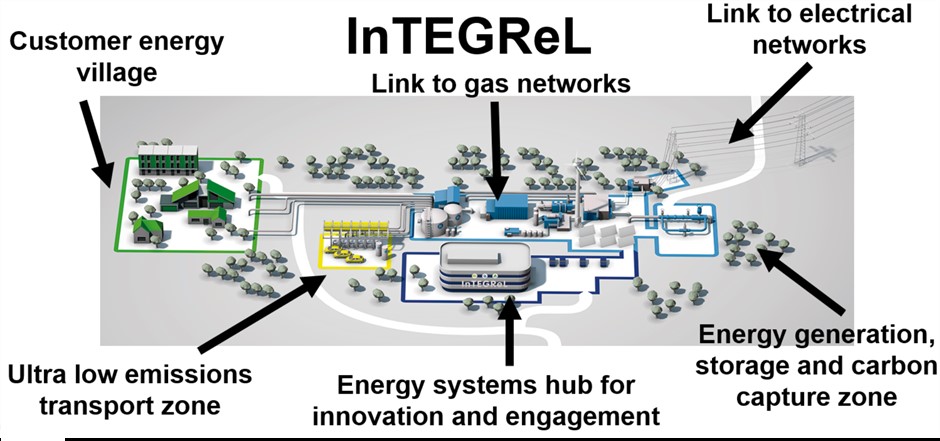

In the report identifying opportunities to grow our capacity, our findings contributed to recommendations for how the energy themes can be progressed and identifying case studies for each. The published case studies include one of CESI’s research demonstrators, The Integrated Transport Electricity Gas Research Laboratory (InTEGReL), as infrastructure offering a whole-systems approach to the UK’s energy use. Newcastle University is working in partnership with Northern Gas Networks and Northern Powergrid to develop the site. Its aim will be to allow academia, industry and government to explore and test new technologies in the electricity, gas and transport sectors in one place, delivering a more secure, affordable, low-carbon energy system.

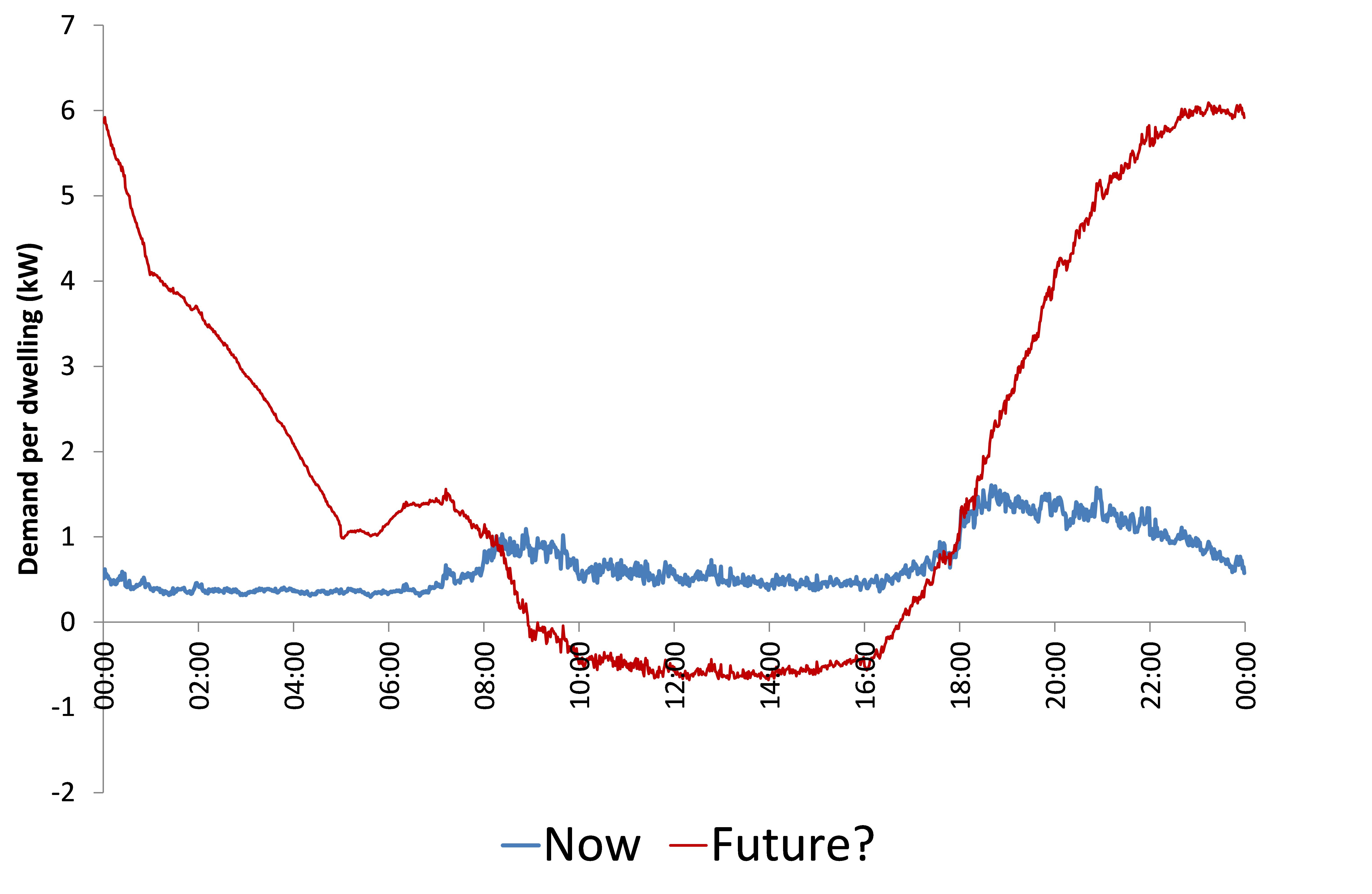

Of particular relevance to CESI are the recommendations for the whole energy systems theme. These include a new interdisciplinary centre for excellence in energy analysis integration and a decarbonisation of heat demonstrator, both of which will make an important contribution to investigations into how we might achieve a net-zero energy future.

UKRI Research and Innovation Infrastructure: Energy

Project team

Professor Phil Taylor

Dr Damian Giaouris

Dr Sara Walker

Dr Zoya Pourmirza

Dr Hamid Hosseini

Laura Brown

Alison Norton

Energy Systems Integration (CESI) and is based at Newcastle University.

Energy Systems Integration (CESI) and is based at Newcastle University.

Durham Energy Institute’s Co-Director for Social Sciences and Health and a Professor at the Department of Anthropology at Durham University. Her research has brought together science studies and governance, through studies of tourism, urban development and land-use planning. Simone’s energy interests lie in relating different disciplinary perspectives on energy and society, including the governance of energy developments, recent transformations of energy markets, ethical questions in energy modelling, and the changing social and political significance of energies, particularly electricity.

Durham Energy Institute’s Co-Director for Social Sciences and Health and a Professor at the Department of Anthropology at Durham University. Her research has brought together science studies and governance, through studies of tourism, urban development and land-use planning. Simone’s energy interests lie in relating different disciplinary perspectives on energy and society, including the governance of energy developments, recent transformations of energy markets, ethical questions in energy modelling, and the changing social and political significance of energies, particularly electricity. Engineering at Newcastle University. A chartered engineer, he has been involved in academia and industry working on the design and optimisation of heating, ventilation and air conditioning services (HVAC) and building fabric since 2003. His work concerns various aspects of building physics, modelling and energy reduction, building retrofit options and occupant

Engineering at Newcastle University. A chartered engineer, he has been involved in academia and industry working on the design and optimisation of heating, ventilation and air conditioning services (HVAC) and building fabric since 2003. His work concerns various aspects of building physics, modelling and energy reduction, building retrofit options and occupant

Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Durham University and a Mid Career fellow in the Durham Energy Institute. She is Manager of BritGeothermal, a UK-based consortium focusing on deep geothermal research both in the UK and internationally.

Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Durham University and a Mid Career fellow in the Durham Energy Institute. She is Manager of BritGeothermal, a UK-based consortium focusing on deep geothermal research both in the UK and internationally.