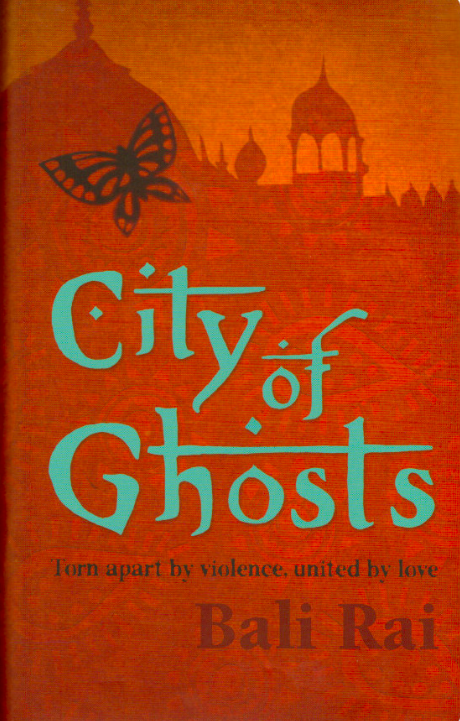

On the centenary anniversary of the Amritsar Massacre, Dr Aishwarya Subramanian reads Bali Rai’s City of Ghosts (2009), a YA novel set in Amritsar against the backdrop of the massacre. Warning: this reading contains spoilers.

On April 13, 1919, on the Sikh festival of Baisakhi, thousands of Indian civilians gathered at Jallianwala Bagh, a walled garden in the city of Amritsar, as part of a peaceful protest against recent actions taken by the British colonial administration. Meetings had been banned a few days previously (there’s been some disagreement over to what extent this particular gathering was a deliberate act of defiance). British Indian army troops, led by General Reginald Dyer, blocked the main entrance to the garden and fired repeatedly into the crowd. Hundreds of Indians were killed, and many more injured, though the exact numbers remain the subject of debate. Dyer’s actions, intended to ‘produce the necessary moral, and widespread effect it was my duty to produce,’ were eventually condemned by the British Indian government and in the British House of Commons (not, however, the House of Lords, or parts of the popular press).

It’s a historical event that, as Bali Rai says in the author’s note to City of Ghosts, has passed almost into folklore in India. I’ve lived most of my life a few hours from Amritsar and only visited Jallianwala Bagh once, and I still remember the blank horror of it—the myth so potent as to become overwhelming in that moment.

City of Ghosts is set in Amritsar against the backdrop of the massacre and the weeks leading up to it, though it moves around in space and time, jumping back to England in 1915, and forward to 1940, when the events set in motion here are truly resolved. The narrative is divided between the perspectives of three young men. Gurdial, a resident of the Central Khalsa Orphanage, has fallen in love with the daughter of a wealthy man, and while she returns his love they see little chance of winning her family’s consent to marriage. Jeevan, Gurdial’s best friend at the orphanage, is lonely and craves a family, and so is easily manipulated into joining a group of anti-colonial revolutionaries. Bissen Singh, an older friend of theirs, is a former World War I soldier, consumed by memories of the English nurse with whom he fell in love during his time in Europe, and dependent on opium. Appearing at various points in each man’s narrative is a mysterious woman, or ghost, who seems to be the only person who knows what’s going on. As a format, this is really effective for a reader who knows the history in question—each short chapter is dated, and as we move closer to the day of the massacre the tension increases to the point that, when the narrative deviated just as things were about to get bad (there are long sections exploring Bissen’s World War I experiences, and shorter ones in which the ghost leads Gurdial on a supernatural journey of discovery), I may have sworn a little.

The three men have drastically differing views on the political events taking place around them. Jeevan fully commits to the idea of an independence struggle, and one which will inevitably involve violence, but it’s always clear that he’s too naïve to have a sense of the larger picture, and that the people who have drawn him in are far more interested in the violence than the independence. Gurdial doesn’t really want to think about politics, and finds Jeevan’s radicalisation dangerous. ‘The revolutionaries were every bit as dangerous as the British. In the end, it was ordinary people who would suffer’ (103). Bissen, on the other hand, can’t understand demands for independence. ‘The Engrezi had brought much that was good and India had prospered as a result’ (80) he thinks; even though in the next moment he contrasts India’s poverty with England’s prosperity and cleanliness, it never seems to occur to him that politics might have something to do with this contrast.

These are believable characters (who doesn’t want an uneventful life?), but as protagonists for a novel about an important historical event they can feel rather disappointing. By presenting its protagonists with a choice between apathy and the monstrous violence of Jeevan’s revolutionary cadre (implied to be itself a product of British manipulation), the book makes Gurdial’s ‘well, both sides are dangerous’ stance seem the only reasonable option. Or it would be, were it not for the minor characters around them who, in similar circumstances, have come to very different conclusions. Fellow WWI soldiers express anger and disillusionment to Bissen Singh; one of them resolving after the war to ‘take up my gun and help to chase these devils from my land’. And Jeevan and Gurdial have been raised in the same orphanage as Udham Singh (to whose memory the book is dedicated), who is only a few years older than them.

Udham Singh’s perspective forms perhaps the most interesting aspect of the book. Singh is known to the admiring younger boys as an activist and member of the Ghadar Party; in 1940 he will assassinate Michael O’Dwyer, the lieutenant governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre. The novel begins with a short account of the shooting, and we later read extracts from his prison diary, in which he hopes only for an end to imperial rule. At the end of the book and immediately after the massacre, the ghost Heera tells Gurdial that one day Udham Singh will set the spirits of the dead free. There are moments in City of Ghosts where it feels as if the fragmented narratives and perspectives are allowing the book to shy away from taking a stand—but this feels like a clear one.

City of Ghosts was published in 2009; I don’t know if it was ever explicitly linked to the 90th anniversary of the massacre. Reading it in 2019, in the days leading up to the centenary, was a very different experience than I suspect it would have been ten years ago. Over the last few years, thinking about the legacy of Britain’s imperial past has become more mainstream within Britain than I ever remember it being. In the wake of the 2016 referendum in particular, ‘imperial nostalgia’ has become ubiquitous as an explanation for people’s belief in a plucky, independent Britain that is also somehow a geopolitical powerhouse. At the same time, as movements like Rhodes Must Fall and activism that works to decolonise museums grow to greater prominence, there’s an increasing acknowledgement of imperial atrocities in the public sphere. On a trip to Amritsar in 2017, Labour MP (and mayor of London) Sadiq Khan called for an official apology for the massacre from the British Government; while British political figures, including the current Queen, and (this week) the current Prime Minister, have expressed regret, there has never been a formal apology.

But the idea of an ‘apology’ is itself a fraught one. Calls for such an apology over the years have frequently cited Winston Churchill’s claim that the massacre was ‘an episode without precedent or parallel in the modern history of the British Empire … an extraordinary event, a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation’—even the author note at the end of City of Ghosts begins with it. (n.b. I’m never sure what to make of this quote and its widespread usage, given Churchill’s well-documented attitudes towards India—perhaps the point is something like ‘even Churchill thought they’d gone too far’?) Theresa May’s recent apology echoes this language, calling the incident a ‘shameful scar on British Indian history.’ As the historian Kim Wagner has pointed out, treating the massacre as an isolated event rather than a consequence of imperial rule, as the Churchill quote invites us to do, works to absolve the British Empire as a whole, treating it as a largely benevolent structure occasionally subject to violent aberrations (which can be blamed on individual bad actors), rather than a violent system in itself.

So how does City of Ghosts fit into all of this? I’m not entirely sure. The fragmented narrative and the range of perspectives make it easier to read the massacre as the complex result of multiple factors all brought to a head, make it possible to condemn the incident without oversimplifying. But then there’s Singh’s ‘freeing’ of the dead, presumably through the death of O’Dwyer—can the death of one man within the system really absolve anything? Even Singh doesn’t entirely seem to think so, whatever the ghost Heera may say. Ultimately the book feels as if it’s shying away from these larger questions—as if, like Gurdial, it would rather just not get too involved. Gurdial is the only one of the three protagonists who survives; perhaps there’s a lesson there.

Aishwarya is a former CLUGG member. Her doctoral thesis examined the effects of decolonisation upon narrative spatiality in mid-twentieth-century British children’s fantasy. Aishwarya also led a postdoctoral project with the Children’s Literature Unit and Seven Stories, ‘Networked Voices: Connecting BAME Activism in Children’s Literature,’ which investigated and visualised networks of antiracist activism in contemporary British children’s literature. The Children’s Literature Association (ChLA) International Committee has just announced that Aishwarya will be one of the three panelists for the 2019 sponsored panel, focusing on BAME Children’s Literature in the United Kingdom, at the ChLA Conference in June. Aishwarya’s other posts on the CLUGG blog include ‘Book Burning with the Borribles’.