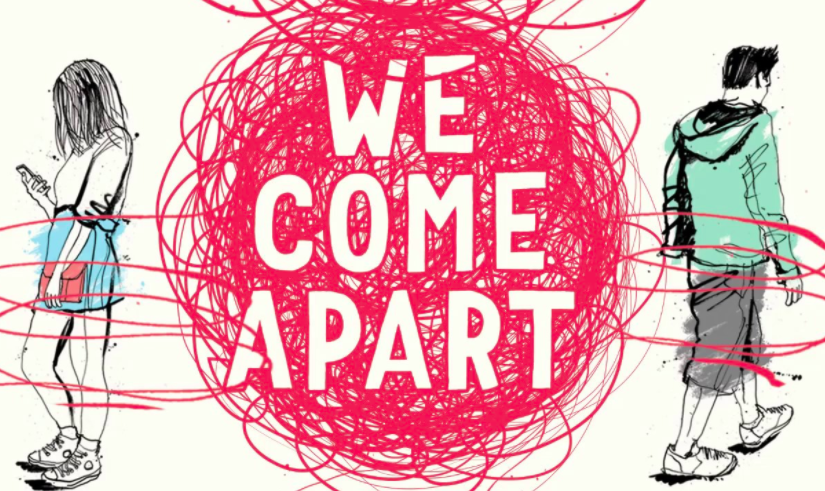

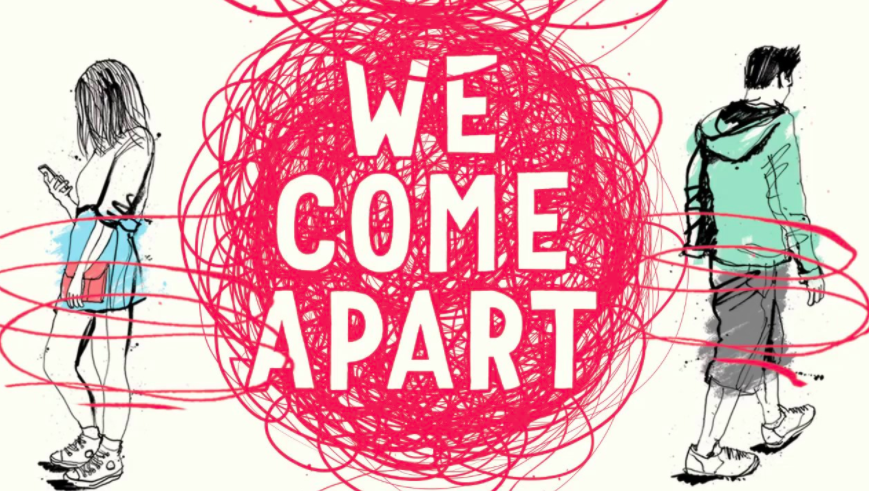

Liz Flanagan, teaching fellow in creative writing and author of Eden Summer (David Fickling Books, 2016), recently chaired an event at the School of English with Brian Conaghan and Sarah Crossan to explore their co-authored verse novel We Come Apart (Bloomsbury, 2017). Here are some of Liz’s thoughts on the evening.

I was delighted to chair this event. For me, Brian and Sarah are two of the most important contemporary YA authors, and I love the fearlessness of their writing, both in its form and content. They tackle urgent and complex subjects, while telling stories in unusual and innovative ways.

Sarah and Brian’s working relationship began at the award ceremony for the Carnegie Medal 2015, when Sarah was shortlisted for Apple and Rain, and Brian for When Mr Dog Bites. At that time, Brian was thinking of writing a novel in verse and he asked Sarah about the form. They began corresponding via WhatsApp, sending messages and chunks of text back and forth in what became a swiftly unfolding digital conversation. The whole novel was written this way, its authors working in different countries, not meeting in person until afterwards.

We Come Apart is a love story that doesn’t shy away from darkness and difficulty, beautifully told in verse, with two narrative voices. At the early draft stage, the authors each wrote a section and sent it to the other, in a kind of creative tennis match. At first, Brian wrote the character of Nicu and Sarah created Jess’s voice. Both authors spoke about how different this was from their usual creative process in having to relinquish control of planning and respond to what they received. They found the quality of their writing improved because they were working collaboratively. They also learned about their own process by seeing the differences in the other’s working style (it definitely sounded as if Sarah was more of a planner than Brian!). However, in the later editorial stages, the process slowed down, and both writers worked on each character’s sections. A love story seems perfect for this dual narrative approach, with its layered perspectives, so that each character is shown to be struggling via their own interiority, but is also seen with compassion and understanding through the eyes of the other.

The authors described their careful approach to the depiction of difficult topics such as the domestic violence of Jess’s home life. Sarah wanted to write the scenes just explicitly enough, so that any young person who had experienced similar abuse would recognise what was happening; but so that it wouldn’t be traumatic for those readers who weren’t yet ready to understand the violence of the situation.

I asked Brian and Sarah about the issue of writing in the voice of someone from an under-represented group: in this case, that of Nicu, who is Romanian, of Roma ancestry. Brian talked about his experience of working with Roma teenagers, and how that fed into the creation of Nicu’s speech patterns, and both authors cited the extensive research they’d undertaken. They discussed the importance of privileging and amplifying ‘own voices’ narratives, while also resisting the idea that, as writers, we can only create from our own lived experience.

The conclusion to We Come Apart feels nuanced and in keeping with the subtle balance of light and shade within the novel as a whole. Sarah spoke about one particular tantalising WhatsApp exchange as they approached the end. She could see the little dots told her ‘Brian is writing’, but it took long minutes for the response to appear. They finally wrote three versions of the ending. I had an odd experience on first reading the novel: I think the ghost of the ending not chosen was haunting my perceptions, and I was braced for a more brutal denouement that didn’t come. However, on second reading, I could more fully appreciate the satisfying end to Jess and Nicu’s story.

Inspired by speaking to Brian and Sarah, I now want to experiment with collaborative writing in my own practice. I’ve started a conversation with a writer I admire, intrigued by the potential for surprises and innovation that these authors describe, and I’ve also devised a workshop for collaborative writing that I’ve begun using in my teaching. I’m very grateful to Sarah Crossan and Brian Conaghan for sharing their experience of working together, and to Dr Lucy Pearson for inviting me to chair their conversation.

The event was organised as part of the Newcastle University Postgraduate Open Day, and presented in association with Seven Stories. Photographs by Rachel Pattinson.