Although the name “Bletchley Park” is recognisable to many today, the nature of the important work carried out by codebreakers stationed there during the Second World War was not fully understood until relatively recently.

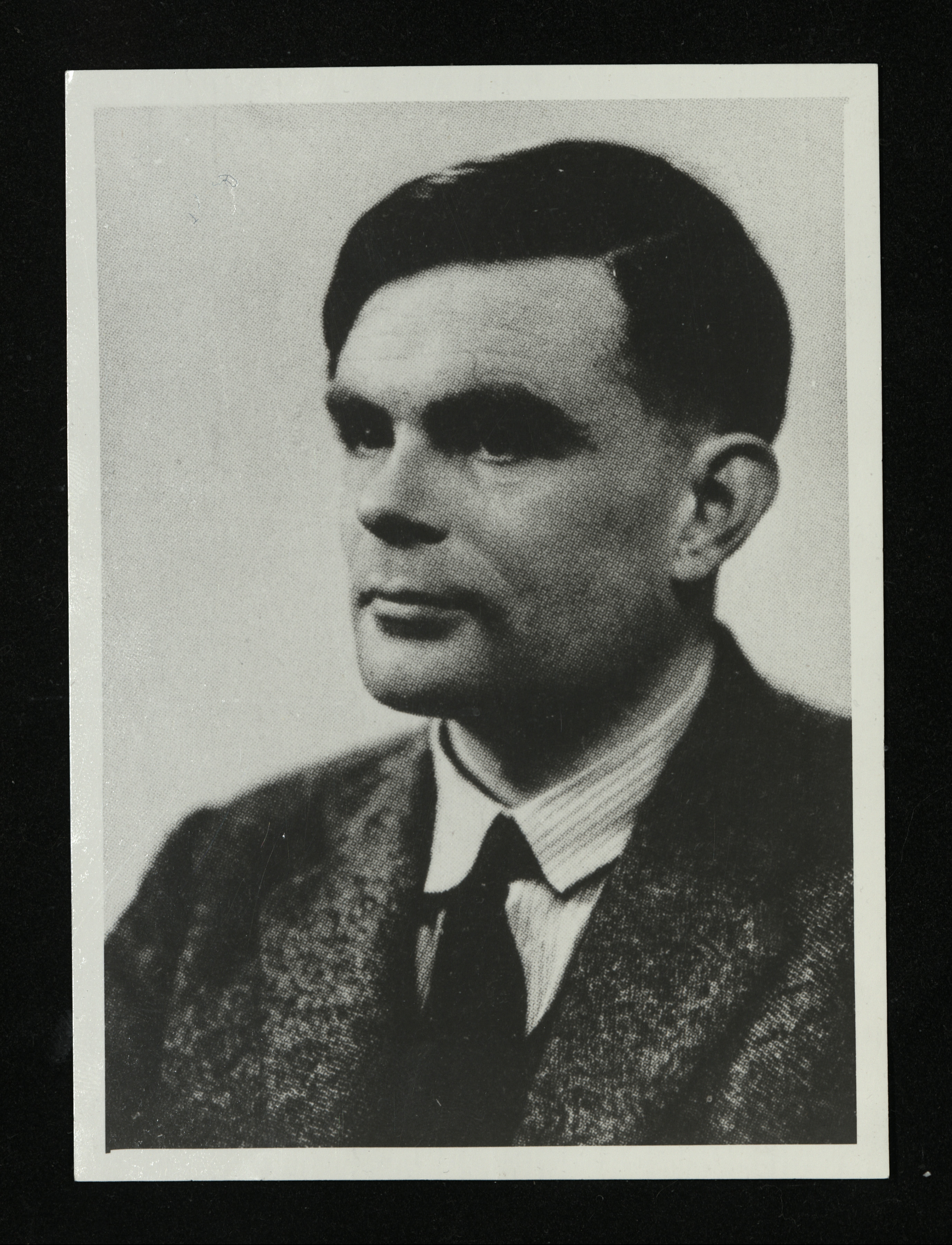

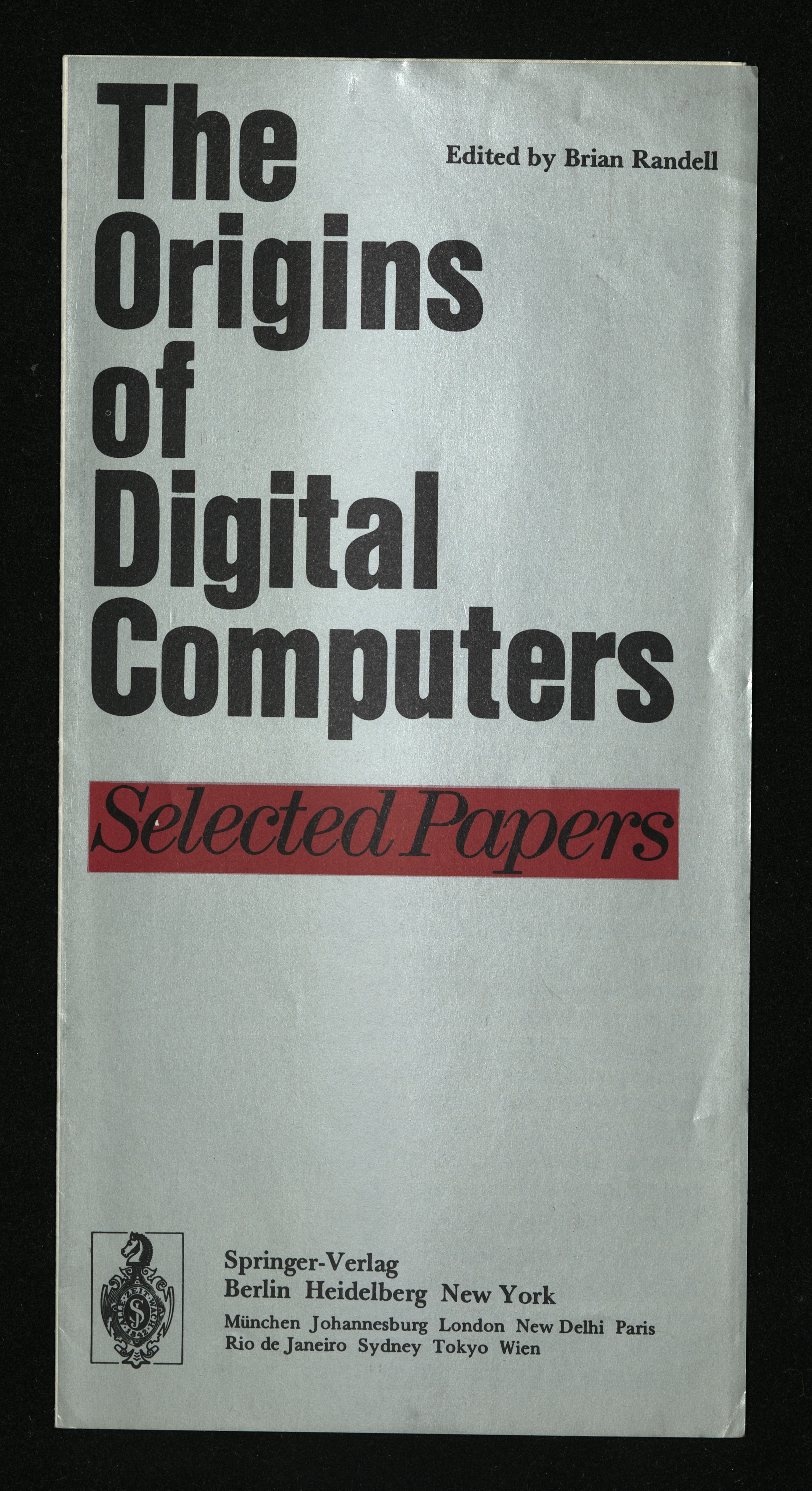

Emeritus Professor of Computing at Newcastle University, Brian Randell’s interest in the early history of the computer led him to publish a paper in 1972 entitled “On Alan Turing and the Origins of Digital Computers”. In this paper, Professor Randell outlined his ongoing investigation into the secretive work carried out by a team of mathematicians and logisticians at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. This work aimed to crack German code and would ultimately result in the creation of Colossus, the first large-scale electronic computer. Professor Randell was particularly interested in the role played by Alan Matheson Turing (1912-1954), as well as that of John von Neumann (1903-1957), Tommy Flowers (1905-1998) and others at Bletchley Park during this time.

At the time, the details of Turing and his colleagues’ contributions to the war effort remained largely secret, with information pertaining to Bletchley still classified. As a result, Turing was instead known within scientific communities for his post-war work at the National Physical Laboratory on the Automatic Computing Engine, completed in late 1945, and at Manchester University.

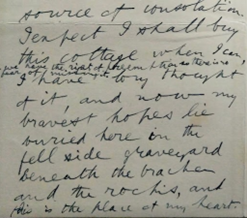

In her 1959 biography of Alan, his mother, Sara Turing, wrote that during the war her son had been “…taken on as a Temporary Civil Servant in the Foreign Office, in the Department of Communications”, but stated that “no hint was ever given of the nature of his secret work, nor has it ever been revealed”. Equally uncertain was the progress that had been made at Bletchley Park regarding the development of computational machines, with the assumption being that the war largely delayed work on these sorts of devices.

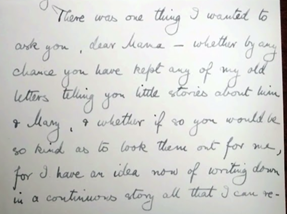

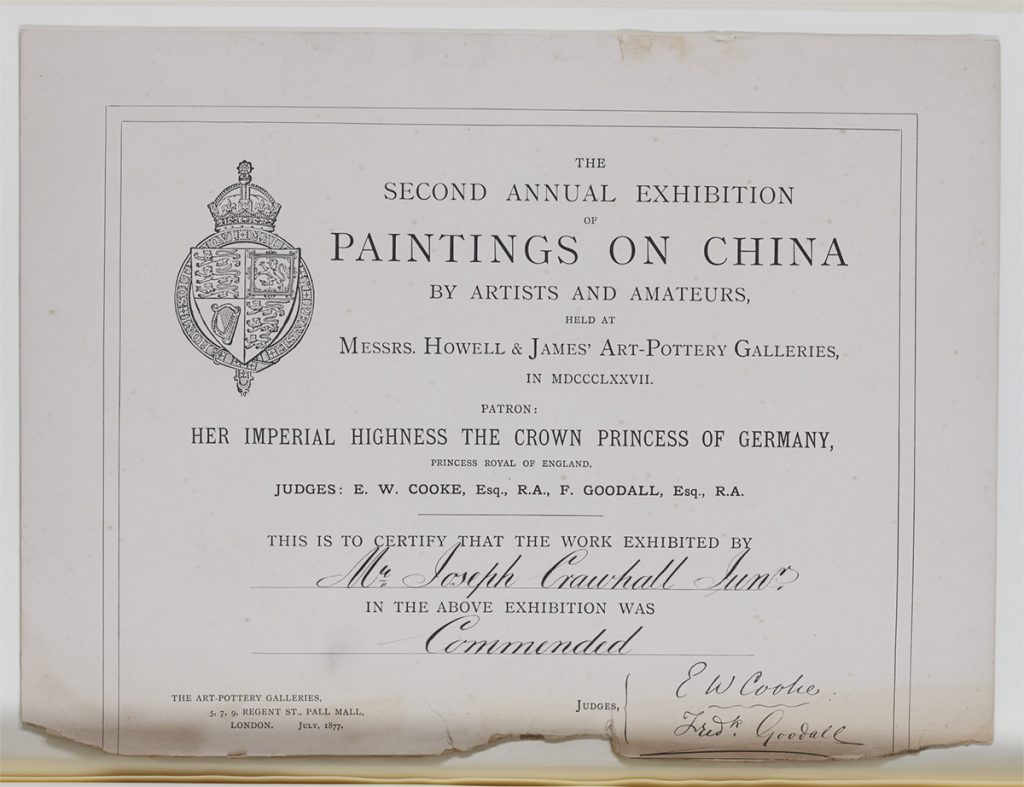

Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives hold the papers of Professor Brian Randell, which span over four decades and document his professional and academic life. Included in this archive are multiple folders of correspondence relating to Professor Randell’s work on the early modern computer. These include the original correspondence from Professor Randell’s ongoing investigation into what was, at the time, still very much a secret part of British history. The secrecy surrounding British cryptographic work during the Second World War was such that a number of the responses Professor Randell received were written “in very guarded terms” so as to avoid breaking the Official Secrets Act.

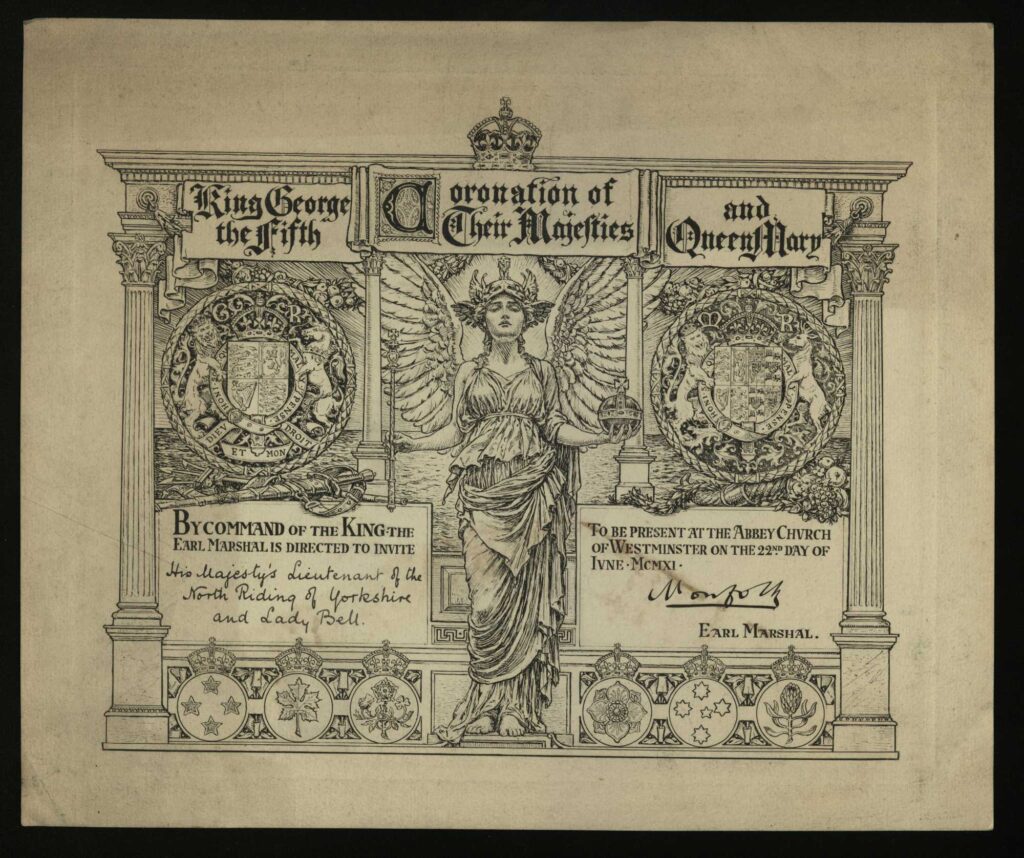

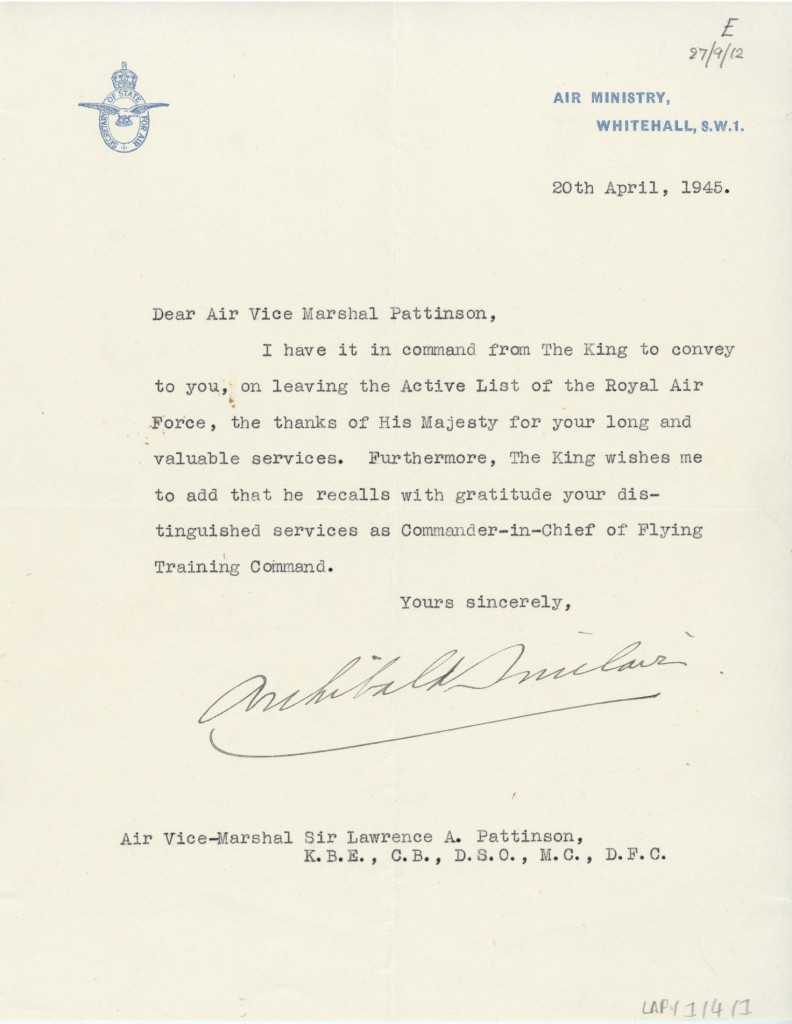

The work and persistence of Professor Brian Randell would eventually result in his invitation to the Cabinet Office in 1975 to discuss the first official release of information about Colossus. After this meeting, he wrote to Turing’s mother, Sara, that “the government have recently made an official release of information which contains an explicit recognition of the importance of your son’s work to the development of the modern computer”.

During the Cabinet Office meeting, Professor Randell was told that the Government would facilitate interviews with leading members of the Colossus Project, in order to allow him to write an approved official history of it.

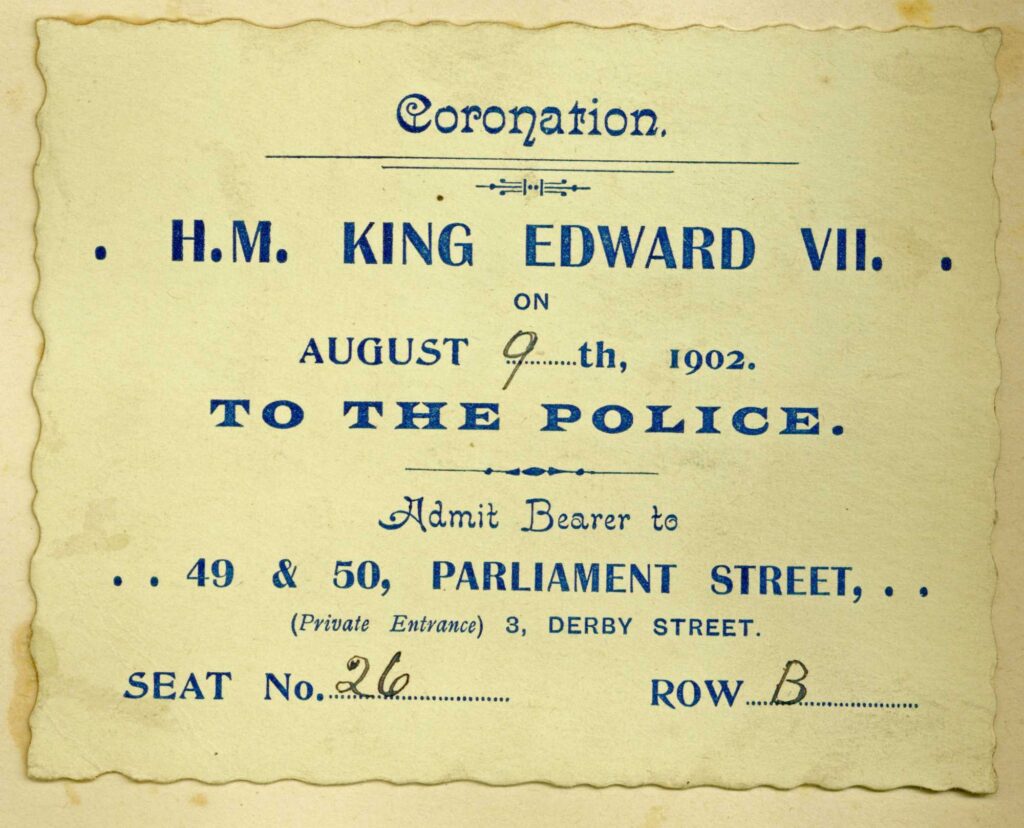

While official recognition of all who worked at Bletchley Park is important, Turing’s legacy has specific relevance for LGBTQ+ History Month. In 1952, Turing reported a burglary of his home to the police. During the investigation, he told police officers that a man with whom he had been having a relationship, Arnold Murray, had been acquainted with the thief. As homosexuality was illegal in the United Kingdom, Turing was charged with “gross indecency” under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 and, after submitting a guilty plea, was given the choice between imprisonment and probation. Accepting probation, Turing was made to undergo hormonal treatment designed to reduce the libido, also known as chemical castration.

His conviction also led to the removal of his security clearance, meaning he was now barred from employment by the British Government, who had engaged him in cryptographic consultancy work at GCHQ following the war. This decision was influenced in part by the recent spying scandal involving Guy Burgess, a British diplomat and double agent who had been passing official secrets to Russia. The actions of Burgess led to an investigation into security standards across the Foreign Service, and his sexuality led to “a highly confidential enquiry in the Foreign Office about the security risks of employing homosexuals”. When the Sexual Offences Act was passed through Parliament in 1967, a bar of any homosexual individuals working for the Foreign Office was imposed and was only repealed in 1991.

Alan Turing died at the age of 41 by in 1954 at his home in Wilmslow, England. An inquest at the time ruled the cause of death to be suicide, however this has been disputed both by Turing’s mother, Sara, and more recently, academic Professor Jack Copeland, who believes Turing’s death to have been an accident caused by carelessness during scientific experiments electrolysing solutions of potassium cyanide.

While Professor Randell’s persistent research helped to shed light on the scientific contributions of Turing and his colleagues at Bletchley Park, it was only in 2013 that Alan Turing was granted a posthumous royal pardon for his conviction of Gross Indecency. Three years later, the British Government introduced “Turing’s Law”, which allowed for the pardoning of 75,000 other men and women convicted of homosexuality under historic anti-gay laws in Britain.

As LGBTQ history month draws to a close, we have an opportunity to remember a historic member of the queer community who had a significant impact on both the trajectory of world history and the advancement of computing science. Turing has, in recent years, become the focus of a biopic (2014’s The Imitation Game) and the face of the fifty-pound note, whilst a museum at Bletchley Park commemorates and informs the public of the crucial scientific work carried out there during the Second World War. Yet it is important to bear in mind that this history is one that has only recently been revealed, much to the credit of researchers and academics such as Professor Brian Randell, who have allowed Turing and his colleagues to take their respective places in British, scientific and queer history.

More information about the Professor Brian Randell archive can be found here.

Watch Professor Brian Randell discuss his work relating to Colossus at the National Museum of Computing in 2013