The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode two: an Ancient Monument

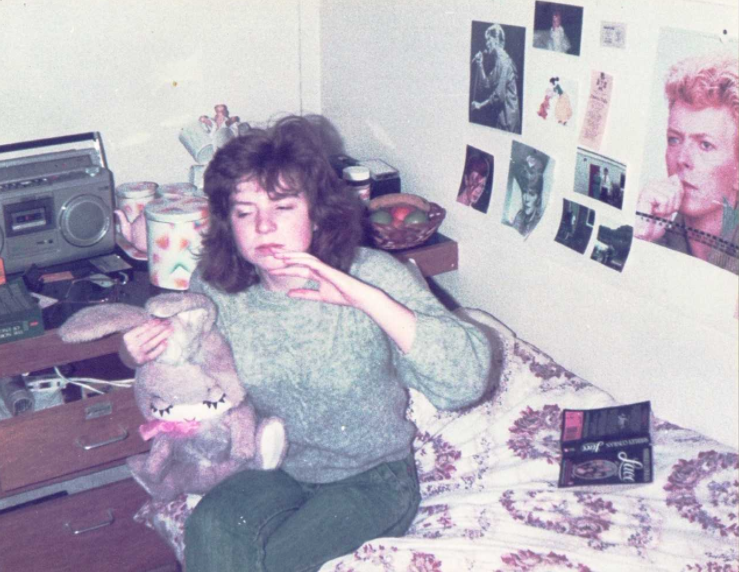

Driving to the station to catch the train to Newcastle University last September my mind went back to 1984 when I was starting university for the first time. Back then, my mum and dad drove me from Dundee to Edinburgh, where I was to spend four years studying English literature – and making friends that I’m still close to today.

Now, however, my mum’s sadly no longer with us, and rather than being an 18-year-old excited about leaving home for the first time, I’m 50 years old, married, and living in the Perthshire countryside with my husband, greyhounds and chickens.

But the me of today still has a few things in common with that eager teenager: for one thing, my taste in music hasn’t changed much – David Bowie is blasting out of the car’s CD player, just as he was back in the 1980s, although back then it would have been a cassette player. And the 50-year-old me was also excited about starting a new degree, although a bit nervous about what it would entail.

Even getting to this point had been a bit of a journey: having decided to apply to do an MLitt in children’s literature, one of the first steps was pulling together the information to prove I met the entrance requirements. Essentially what I needed was a 2:1 or higher in a related subject, so that should have been tickety-boo: but I hadn’t reckoned with my great age.

The application form required ‘transcripts’, by which it meant a documentation that showed all the courses I had taken – and the marks achieved – in my undergraduate degree. I had my degree certificate, but had never even heard of transcripts.

A call to my alma mater – the University of Edinburgh – confirmed that they could send me an academic statement, but the kind young man on the other end of the phone explained it might take some time. ‘You see, our records don’t go back that far, so we’ll have to dig it out of the archives,’ he said. Yes, it seems there is a room somewhere in Edinburgh University filled with big books containing the details of past students – and to retrieve mine would involve someone physically going to the room and wading through these tomes and taking a copy. This process was set in motion, and when the document finally arrived, it turned out to be merely confirmation of my first degree and overall result. The ever-helpful and patient postgraduate admissions staff at Newcastle confirmed that this was okay – they are happy to be flexible with mature students, it seems – so the application progressed, and ultimately was successful.

Arriving at the university campus in all its freshers’ week pomp also brought back memories, although there were of course some differences: this time, I was (sadly) largely disregarded by the eager young students peddling leaflets about societies, or offering cut-price beers or nightclub entry to people who looked like they might be freshers. ‘I’m a student too,’ I screamed (but silently).

After the process of registration was completed – one member of staff kindly confirmed I wasn’t quite the oldest she’d seen that day – I had an initial meeting with my supervisor, Lucy Pearson. More of an informal chat, we discussed my areas of interest and she recommended some initial reading. She also reminded me of events set up to welcome postgraduates, including a get-together (with quiz!) held by the Children’s Literature Unit, and a drinks reception organised by the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics.

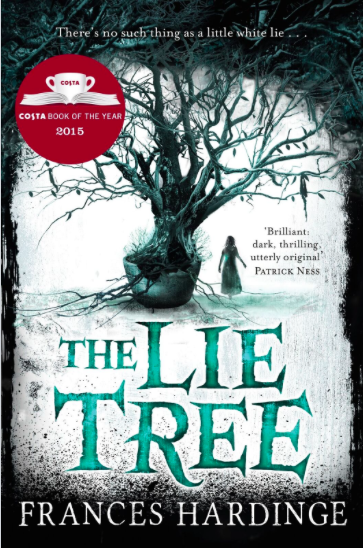

The latter, I confess, was an eye-opener: chatting with a couple of recent graduates about to embark on PhDs, I enquired about their subject areas, and realised I didn’t even understand what they were. What on earth was ecocriticism, for example (when I found out I immediately started wondering if I could apply it to Elinor M Brent-Dyer’s Chalet School books – and why not?).

All in all, it was a lot to take in, and a lot to think about – would this ancient monument be able to cope?

We really hope so! In the meantime, if you missed episode one of A Fresher at Fifty, read it here.

children and parents looking for supplies to put together fancy dress costumes inspired by their favourite characters. (For the record, I’ve had a Cat in the Hat, Thing 1 and Thing 2, two witches from Room on the Broom, a Katniss Everdeen, a Willy Wonka, and a Gandalf the Grey – all in one day, I might add!)

children and parents looking for supplies to put together fancy dress costumes inspired by their favourite characters. (For the record, I’ve had a Cat in the Hat, Thing 1 and Thing 2, two witches from Room on the Broom, a Katniss Everdeen, a Willy Wonka, and a Gandalf the Grey – all in one day, I might add!)