The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode Five

From Fresher at Fifty to Graduate at 52

The peacocks are quite possibly the most vivid memory from my first graduation. Back in the summer of 1988, we had lunch in Edinburgh’s Prestonfield House Hotel, where the savvy waiters hovered refilling glasses of red wine with the tempting mantra ‘you deserve it’. It’s hardly surprising that when we finished eating, and repaired to the garden for some photographs, this new graduate was spotted crawling along the grass trying to persuade the showy birds to play bonnie for the camera.

There were no actual peacocks* present in December when my fellow graduands and I gathered in the rather grand King’s Hall for graduation number 2 – or ‘congregation’, as it’s called at Newcastle University, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t memorable. For one thing, there was something rather awe-inspiring about walking the same route as Martin Luther King had taken when he received an honorary degree from the university back in 1997. For another, it was great to catch up with some of the friends and acquaintances who were graduating on the same day.

And frankly, it was also pretty great to have got to the point where I was graduating at all.

It was back in 2017 that I decided to study for a research degree in children’s literature, working for the MLitt part-time over two years. Looking back, I had dived into the application process in a fit of naïve enthusiasm, without any real idea of what it would be like. I had imagined it might be tricky to navigate professional commitments with my new life as a student (stopping work was never a financial option for me) but had blithely supposed it would all be fine, really. I also had vague apprehensions that academia might have moved on a bit in the last 30 years, but confidently felt that I could deal with that: bring it on, said my 50-year-old self.

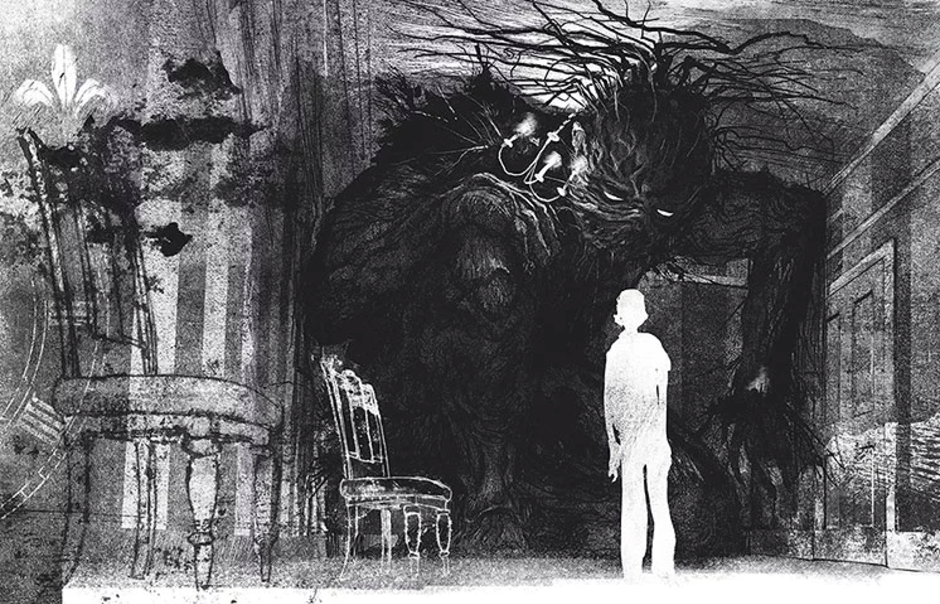

I’ve written in a previous blog about the various challenges, particularly in re-learning academic writing and balancing the various demands that are inevitable at my time of life, including my dad’s increasing care needs. Surprisingly (at least to me), however, the experience of doing the degree was that, overall, it alleviated rather than added to these stresses. Even at the height of dissertation writing, with deadlines looming, I was able to lose myself completely in writing, rewriting, and yet more rewriting – so much so that I once ended up on a train to Glasgow instead of Edinburgh because I was engrossed. That kind of feeling is pretty wonderful.

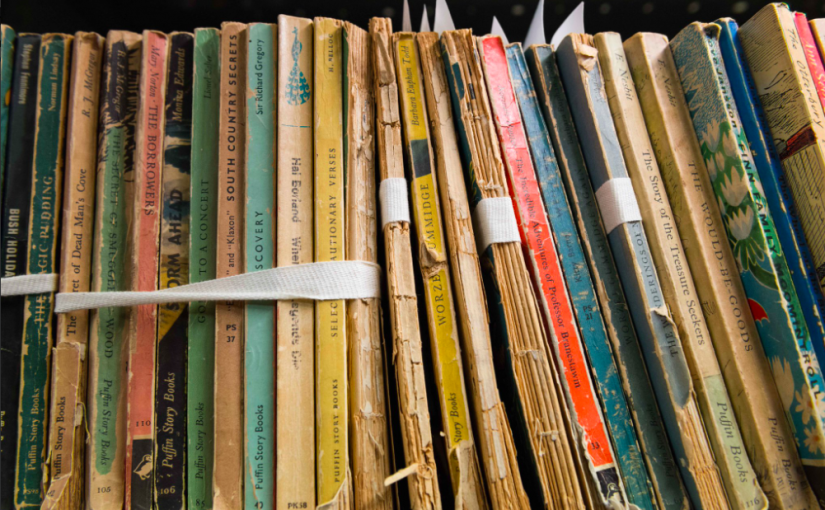

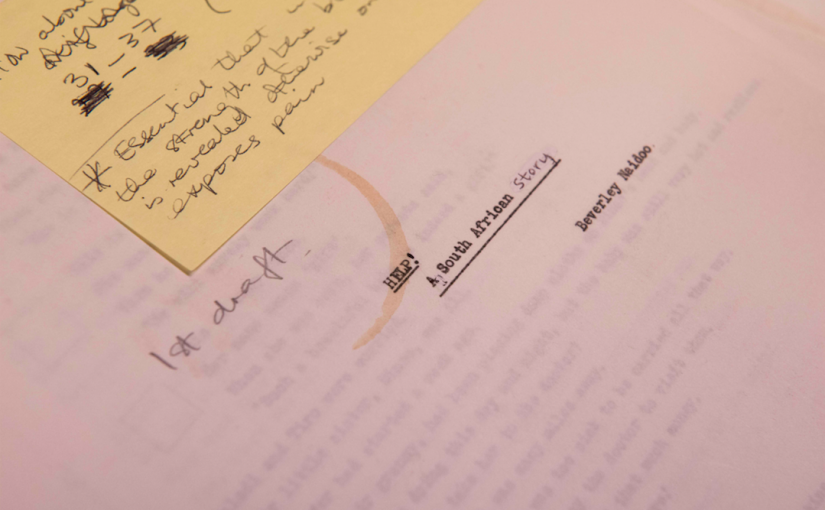

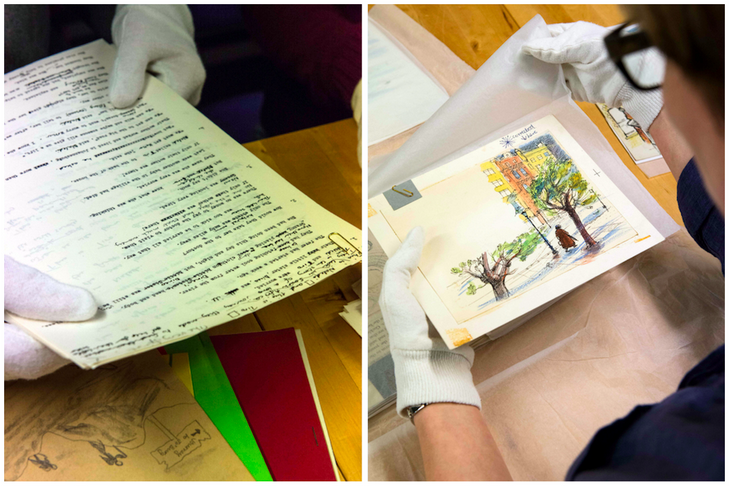

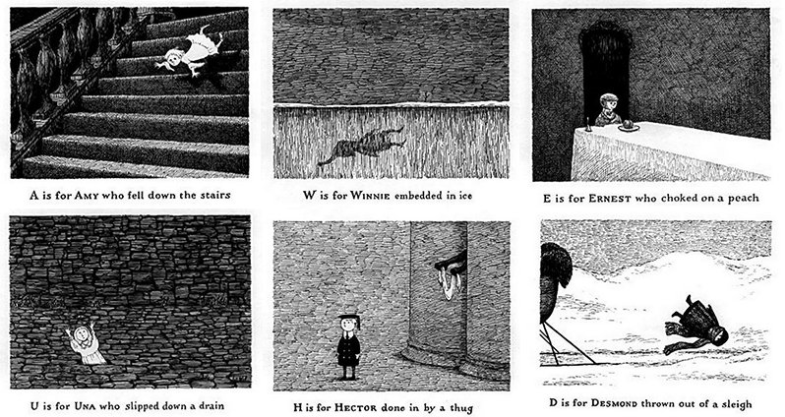

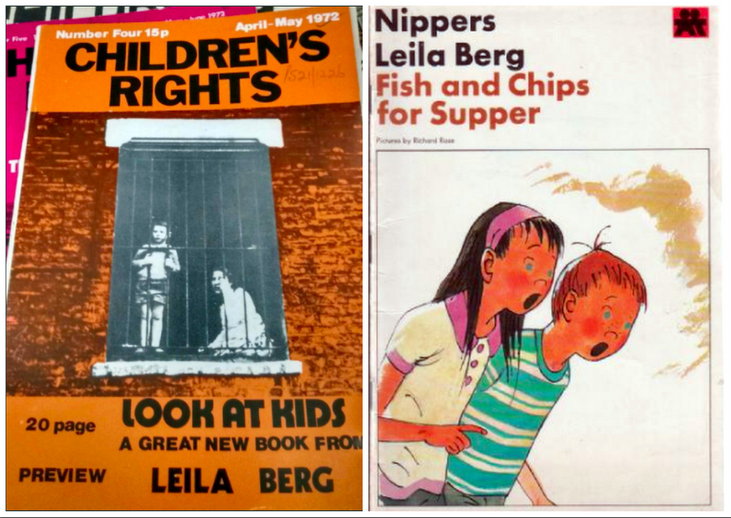

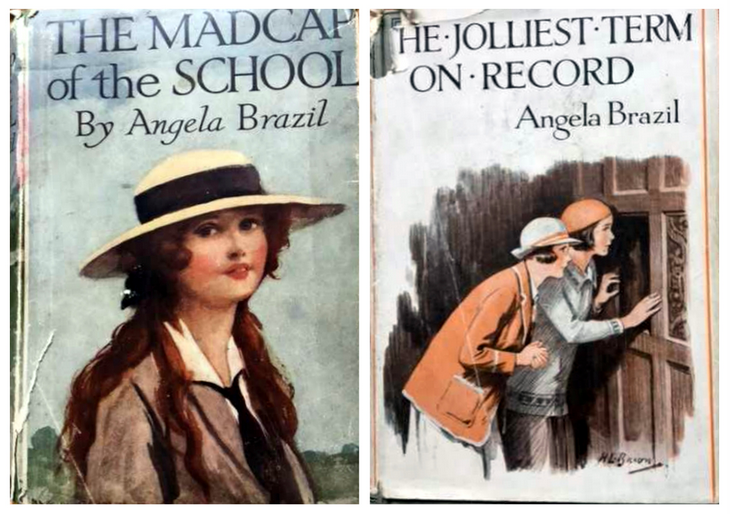

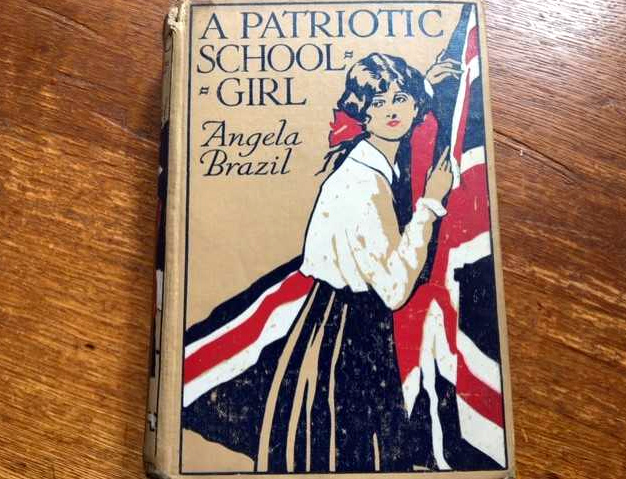

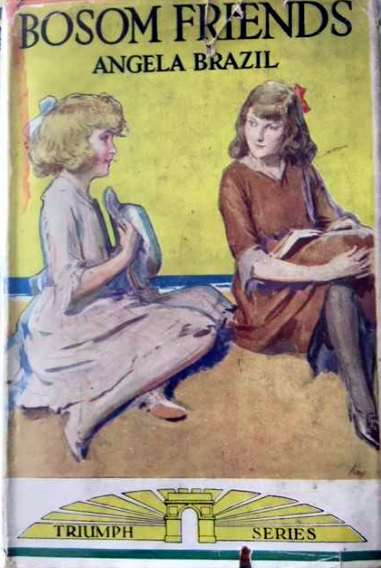

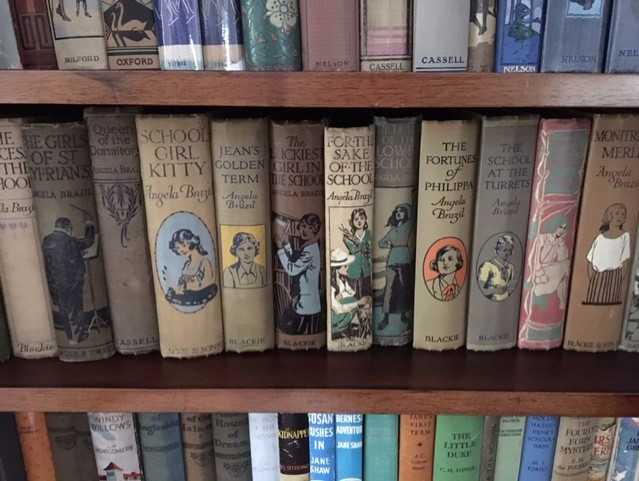

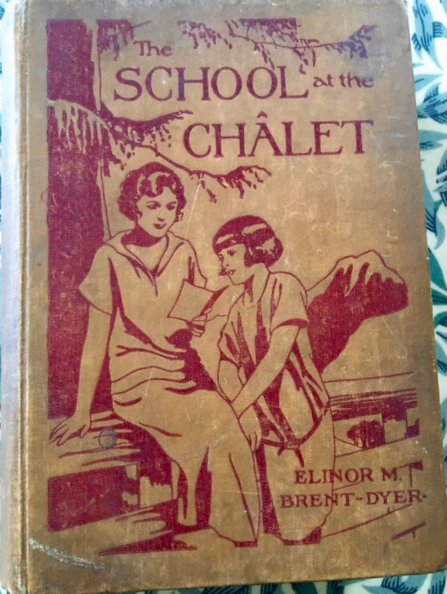

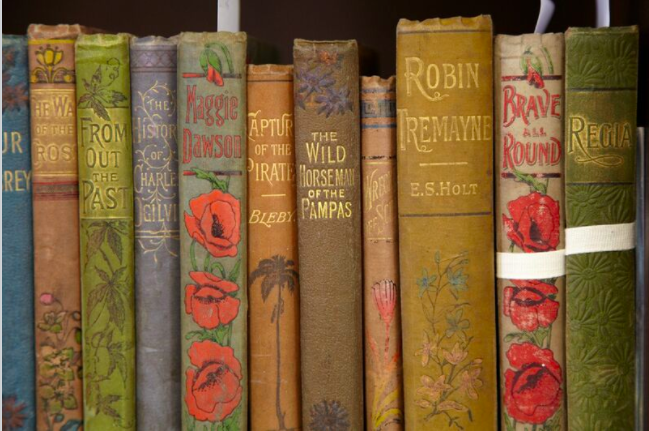

On reflection, doing the degree also gave me some fabulous opportunities. As well as doing my own original research on mid-20thcentury girls’ books, I sat in on the undergraduate children’s literature course, which introduced me to things I probably wouldn’t have otherwise read (Patrice Lawrence’s Indigo Donut was a particular favourite). I spent some time in the Seven Stories archive wallowing in Noel Streatfeild’s diaries and letters, which was great fun and a new experience. I heard some fabulous speakers at university events and made some good friends. I also learned to think and respond more with greater critical clarity – not just to literature, but in all aspects of life.

I can’t say that I really felt I truly got to grips with academic writing, and my dissertation (on radicalism in Mabel Esther Allan’s early books) could have been infinitely better. But I did okay, and my overall degree result was sufficient should I decide to apply to do a PhD in the future.

I miss my life as a student and my frequent trips to Newcastle. Yes, it was tough, but it was also wonderful. I’d very much recommend it; indeed, I might, at some point, be back…

*when I say there were no ‘actual’ peacocks there in December, I think my dad’s smile on the day suggests he was ‘as proud’ as one.

Jennifer, we hope that you will soon be back at Newcastle.

For blog readers wanting to know more about the MLitt programme, see the Children’s Literature Unit page on the Newcastle University website. Highlights of the Seven Stories Collections can be seen here.