Over the last few months there has been considerable debate regarding the establishment of ‘safe-space’ on university campuses around the world, with the anxiety expressed that they act to shut down free speech. In a world apparently dominated by post-factual political rhetoric the need for debate and the interrogation of diverse views seems more important than ever. This is well exemplified by the columnist Timothy Garton Ash. So, I guess putting the phrase ‘safe space’ in a blog post could be considered attention seeking. Actually it is not. It is a phrase which has emerged from a series of research projects in which I have been capturing views of a new and established teachers and lecturers, from primary, secondary, Further and Higher Education settings about practices and environments in which they experience professional learning.

The significance of ‘safe-space’ is evident in my last blog post, in which I concluded with the question, How do we create modern day collaborative learning experiences in which our student teachers will experience solidarity with each other and with the learners, will be given permission to be productively creative and do so in a safe space in which each of them can become the best teacher they can be? This post picks up the theme where I left off, and also draws on the keynote I gave at the UCET annual conference.

The focus for this second post is the link between opportunities to learn collaboratively and learning as ‘conceptual change’. Whilst I have frequently in the last 15 or so years described learning as change to my PGCE and Masters students it is only recently that I have come across the idea of conceptual change. For this I thank Peter Davies at Birmingham University for creating a team of researchers from three universities. So Peter and I, along with Celia Greenway (also of Birmingham University) and Dan Davis and several of his colleagues (of Cardiff Metropolitan University) are exploring student teachers experiences’ of their own learning to teach using ‘conceptual change’ as our theoretical basis. In essence conceptual change is the experience which we go through when we have to consciously rework and reframe an idea or understanding that we have previously accepted. This idea has been particularly well demonstrated in children’s learning of scientific phenomena. Take for example the fact that typically children conceptualise the world as flat because that corresponds with their early experience of it. Developing an understanding that the world is actually a globe requires a reworking of the flat earth construct. This is known as conceptual change.

In our current recent research we are trying to determine the nature of conceptual change in learning to teach and some of the factors that might promote this change. Without attending to the entire research findings there are some key aspects to note and one of those is that the phenomena of learning to teach is essentially a complicated one. Part of the complication is that student teachers are not inexperienced in the phenomenon of teaching, indeed they have had years of experiencing teachers and teaching through being taught. For many this leads to a naïve, but possibly strongly held, conception of what it means to learn and act as a teacher. Because it is a strongly held conception student teachers may be resistant to more systematic scrutiny of the phenomenon of themselves learning to teach. And of course this is doubly complicated because the phenomena in which they are immersed, rather than being something which they can simply be instructed in from neutral territory, is an experiential learning phenomena in which they participate. So whilst we may understand the need for a conceptual shift or change during a period of training or education for student teachers this may be a difficult thing to make happen.

This is where collaboration comes in. In our research we have been interviewing students at different stages of their initial teacher education to try to reveal the dimensions of learning that they experience in learning to teach. Using analytical methods appropriate to conceptual change theory it has been possible to identify several key dimensions of learning to teach. Amongst others these include the contexts in which learning happens and the various modes of learning as described by the student teachers. And what we find in analysis of their interviews is that the student teachers highlight interactions with others, but just like other identifiable dimension there is variance evident in in these descriptions. So learning to teach from and with others is evident and this typically include one or more of the school mentors, other colleagues in school, the University tutor and their peers. These ‘others’ have the potential to create a social context for learning. Our analysis of these descriptions has resulted in three broad categories:

- that of recipient of learning from another

- that of a lone enquirer capable of seeking out opportunities evidence and advice but typically doing it individually

- and finally that of co-constructor.

It is this latter group who talk about their learning as a collaborative process. Our analysis of the interviews and combination of the dimensions of learning is leading us to conceptualise patterns of conceptual change experienced by student teachers and to recognise affordances and constraints in this learning. So, for example it is clear, for those people who we describe as co-constructors that they link collaboration and their own learning. It is also clear in the ways that they describe these experiences that sometimes collaboration happens by chance and sometimes it happens by design. This research is ongoing, but even at this early stage it is worth reflecting on.

I am going to do so by focusing on one aspect of my role, as a teacher educator in initial teacher education, through which I and my colleagues apply curriculum and pedagogic decision-making. Sometimes a core aim is to enable student teachers the chance to learn through collaboration by our design. While this might seem an entirely logical approach, it is clear that for many student teachers now genuine opportunities to work collaboratively on real workplace related tasks has become limited. In other words they are not there by design. At this point I think I should re-iterate my view of collaboration (rather than co-operation), as highlighted in the first blog post. I am drawing on the definition of collaboration which was used in a piece of research that Ulrike Thomas and I undertook a couple of years ago.

‘Collaboration is an action noun describing the act of working with one or more other people on a joint project. It can be conceptualised as ‘united labour’ and might result in something which has been created or enabled by the participants’ combined effort.’

To briefly illustrate this here are two such ITE design decisions that we have made over the years at Newcastle University.

Enhancing mentoring through the use of video

We have been interested in mechanisms through which to enhance the mentoring experience and whilst we know from the research cited above that mentoring is not necessarily experienced as collaboration there are some means by which this can be promoted. Altering some of the power structures within a student and mentor relationship can aid the experience of collaboration, and this can be altered through the use of appropriate tools, such as video. As we demonstrated in earlier research this can help the mentor and student teacher work in more co- constructive fashion as the student teachers gain insight into themselves as teachers rather than simply await feedback from others. As a result video can help them to build more open and confident relationship, thus supporting collaboration. Our current cohort of secondary PGCE students (including School Direct) and Employment-based PGCE students (whose QTS training provider is Newcastle SCITT) are being introduced to VEO as one possible tool for enabling video to enhance mentoring as a more collaborative learning experience.

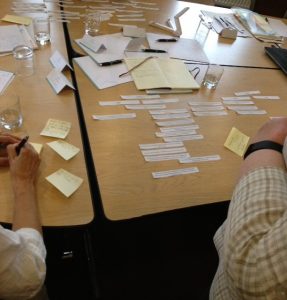

Embedding Lesson Study in the curriculum

As part of our Secondary and Employer-based PGCEs we also use lesson study as a means to ensure that all student teachers experiences peer-collaboration. Lesson study is the practice-based learning element of an M.level module which invites students to develop critical perspectives on teaching thinking skills. During a two day conference they are introduced to thinking skills, metacognitive talk & lesson study. They use Lesson Study to co-plan, teach, observe and co-enquire into this pedagogic approach in their placement schools. This is frequently conducted between subject areas. Students then jointly present their learning outcomes to peers & individually write a reflective commentary. Last year James Rivett, an MFL PGCE student who had worked in partnership with a science student went on to publish a blog post in which he described the experience as one which went beyond ticking boxes to something which felt real and enabled a deeper process of learning. We are looking forward to our 140 students having similar experiences in January and February next year.

In the evidence of student teachers and mentors experiences related to the above examples there is a resonance with the definition of collaboration as an experience of united labour from which something of value is created or enabled by combined effort. They bring me back to the concept of ‘safe space’. For me it is critical that university teacher educators are proactive in answering the question, How do we create modern day collaborative learning experiences in which our student teachers will experience solidarity with each other and with the learners, will be given permission to be productively creative and do so in a safe space in which each of them can become the best teacher they can be? This is because it seems that for some student teachers, at least, collaboration enables them to experience learning as change. At Newcastle University we hope to continue to design experiences that allow this to happen. It is only by achieving this that we will achieve our goal of ‘Inspiring teachers; changing lives and building futures’.

Written by Dr Rachel Lofthouse, Head of Education, Newcastle University.