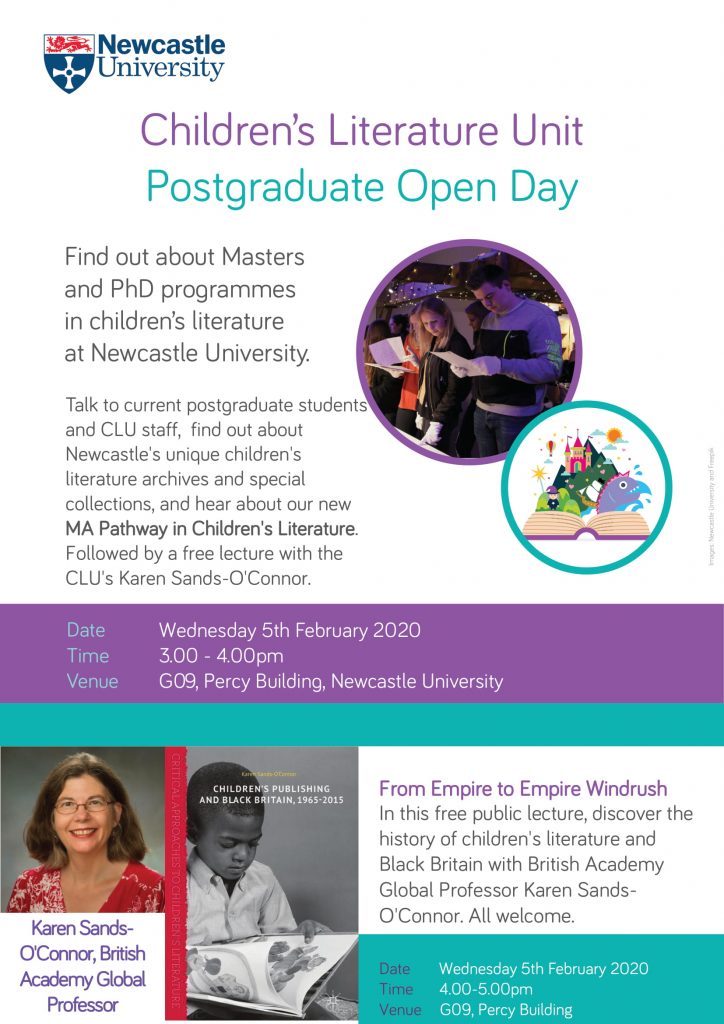

We invite any prospective children’s literature students to visit us next week and hear from current students and staff. All are welcome to the public lecture from Professor Karen Sands-O’Connor. See the poster for information.

The Children’s Literature Unit Graduate Group (CLUGG) holds weekly 2-hour meetings where members pick a relevant theme to discuss together, allowing us as researchers to broaden our academic interests, learn from one other and engage more widely with the Children’s Literature academic community. By posting about our previous sessions, we hope to give you an idea of some of the research interests of CLUGG members, as well as the work that they are currently undertaking.

In this blog post, MLitt Student Enya-Marie Clay looks back on the first few CLUGG sessions of Semester 2. Further posts about CLUGG sessions will feature on the blog in the future, as and when members can contribute, so please bookmark the blog if you’re interested in future updates relevant to all things Children’s Literature at Newcastle University.

Session 1: 30th January 2019

In this session we discussed extracts from Peter Hollindale’s Signs of Childness in Children’s Literature (1997), specifically chapters 1 and 5: ‘The Uniqueness of Children’s Literature’ and ‘Signs of Childness: A Summary and Critical Approach’.

This prompted discussions surrounding key critical questions of the field such as:

We also discussed how Hollindale’s work sits within the broader landscape of scholarship by thinking about how it compares with the prominence of Jaqueline Rose’s work. This led to comparisons with non-British theorists within children’s literature, such as Perry Nodelman, and an exploration of how different social and geographical contexts affect the prominence of different works. In doing this, we also discussed which texts stand out as seminal reading and how these texts connect with the development of children’s literature as a discipline.

We ended the session by planning Semester 2 CLUGG meetings with the view to increasing the variety of activities and interests, such as student presentations and primary texts, and to move towards more student-led sessions now that the academic year is more established.

Session 2: 6th February 2019

In this session we welcomed Rachel Pattinson, the Vital North Partnership Manager, who kindly brought along books from the IBBY UK Selection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities (2017) from Seven Stories.

We spent the session exploring the books and discussing their features. We were all struck by the importance of communal reading as a theme across the books, with many encouraging collaborative reading between the reader and child, such as Morgh-e Sork-e Pa Kootah (The Little Red Hen), which Rachel and Helen read together using the step-by-step guide to unfold the tactile story.

With the collection featuring books in over 40 languages from a variety of countries, we also had the opportunity to discuss how the books reflected their cultures of origin and how this compares with our understanding of children’s literature as British scholars. Yasuhiro Hunimori’s Ren-chan hajimete no mitori: Obaachan no shi to mukiau (Good-bye great grand-ma: A young girl’s first encounter with end-of-life care-giving), an incredibly moving photographic picture book with realistic photos of death, is a good of example of this, as we considered such stark images to be unusual in British children’s literature. This prompted conversation around how representations of trauma in children’s literature vary greatly across cultures and how this can reflect distinct attitudes to children and childhood.

The collection also features portrayals of disability (category 3), a notable example being a graphic novel titled El Deafo (2014) by Cece Bell. It was interesting how this novel transformed the bullying taunt ‘deafo’ into a superhero persona (hence the novel’s title), and thus showed a young protagonist celebrating their own disability. We discussed the novel’s use of speech bubbles, in which the text fades or disappears entirely to reflect the protagonist’s hearing loss, and how these effectively communicated the main character’s disability in a way that was accessible to readers who may not have experienced hearing impairment.

More details about the collection can be found on the IBBY website.

Session 3: 13th February 2019

This week’s session centred around an article provided by doctoral candidate Rebecca Jane titled ‘“Away with dark shadders!” Juvenile Detection Versus Juvenile Crime in The Boy Detective; or, The Crimes of London. A Romance of Modern Times’ written by Lucy Andrew. We used the article to discuss ideas surrounding penny dreadfuls, such as their use in juvenile court cases as Andrew discusses and how their depiction of violence differed in comparison to other periodicals of the time, such as The Boy’s Own Paper.

This led to discussions on ideas from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, such as how lurid descriptions and publicisation of a trial or a punishment can serve as a way of making the public an agent of control. We discussed this in the context of how violence was written about in the 19th century and then thought about how a degree of ‘acceptable’ criminality in the upholding of justice seemed to be a trope of the detective genre more generally.

We then discussed Andrew’s take on class and power tensions in The Boy Detective and explored the idea that penny dreadfuls could be a way of upholding conservatism through subversion; in other words, they can act as an abstract platform to explore ideas of criminality which exhausts the desire for this exploration in real life.

The latter part of the session then looked at ideas about radicalism in children’s literature and how different parenting styles globally can affect childhood experiences and the way that we ultimately come to research children’s literature. This led us to talk about attachment theory, the sacralisation of the mother/child relationship and how children’s literature traditionally reinforces this, and the adult fear of the loss of control over children as they mature. Through considering this, we recognised how our understanding of a text’s intended reader is socially constructed depending on context and how this must be considered when discussing texts.

Photo Credit: Rachel Pattinson, Vital North Partnership Manager, @rachelalmost. Texts from the IBBY Selection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities.

The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode Five

From Fresher at Fifty to Graduate at 52

The peacocks are quite possibly the most vivid memory from my first graduation. Back in the summer of 1988, we had lunch in Edinburgh’s Prestonfield House Hotel, where the savvy waiters hovered refilling glasses of red wine with the tempting mantra ‘you deserve it’. It’s hardly surprising that when we finished eating, and repaired to the garden for some photographs, this new graduate was spotted crawling along the grass trying to persuade the showy birds to play bonnie for the camera.

There were no actual peacocks* present in December when my fellow graduands and I gathered in the rather grand King’s Hall for graduation number 2 – or ‘congregation’, as it’s called at Newcastle University, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t memorable. For one thing, there was something rather awe-inspiring about walking the same route as Martin Luther King had taken when he received an honorary degree from the university back in 1997. For another, it was great to catch up with some of the friends and acquaintances who were graduating on the same day.

And frankly, it was also pretty great to have got to the point where I was graduating at all.

It was back in 2017 that I decided to study for a research degree in children’s literature, working for the MLitt part-time over two years. Looking back, I had dived into the application process in a fit of naïve enthusiasm, without any real idea of what it would be like. I had imagined it might be tricky to navigate professional commitments with my new life as a student (stopping work was never a financial option for me) but had blithely supposed it would all be fine, really. I also had vague apprehensions that academia might have moved on a bit in the last 30 years, but confidently felt that I could deal with that: bring it on, said my 50-year-old self.

I’ve written in a previous blog about the various challenges, particularly in re-learning academic writing and balancing the various demands that are inevitable at my time of life, including my dad’s increasing care needs. Surprisingly (at least to me), however, the experience of doing the degree was that, overall, it alleviated rather than added to these stresses. Even at the height of dissertation writing, with deadlines looming, I was able to lose myself completely in writing, rewriting, and yet more rewriting – so much so that I once ended up on a train to Glasgow instead of Edinburgh because I was engrossed. That kind of feeling is pretty wonderful.

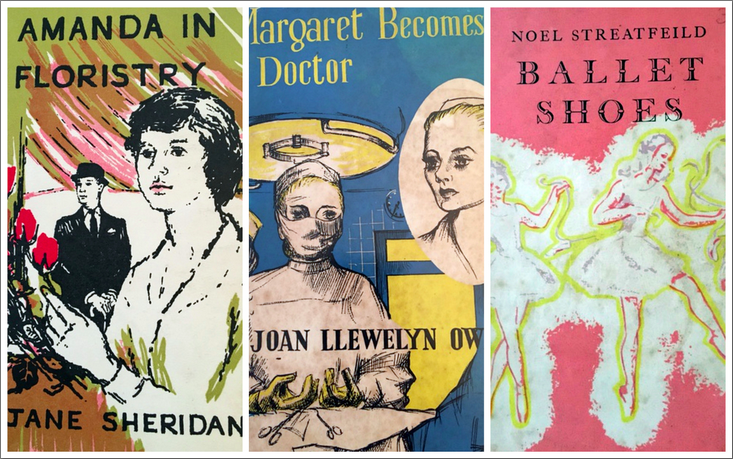

On reflection, doing the degree also gave me some fabulous opportunities. As well as doing my own original research on mid-20thcentury girls’ books, I sat in on the undergraduate children’s literature course, which introduced me to things I probably wouldn’t have otherwise read (Patrice Lawrence’s Indigo Donut was a particular favourite). I spent some time in the Seven Stories archive wallowing in Noel Streatfeild’s diaries and letters, which was great fun and a new experience. I heard some fabulous speakers at university events and made some good friends. I also learned to think and respond more with greater critical clarity – not just to literature, but in all aspects of life.

I can’t say that I really felt I truly got to grips with academic writing, and my dissertation (on radicalism in Mabel Esther Allan’s early books) could have been infinitely better. But I did okay, and my overall degree result was sufficient should I decide to apply to do a PhD in the future.

I miss my life as a student and my frequent trips to Newcastle. Yes, it was tough, but it was also wonderful. I’d very much recommend it; indeed, I might, at some point, be back…

*when I say there were no ‘actual’ peacocks there in December, I think my dad’s smile on the day suggests he was ‘as proud’ as one.

Jennifer, we hope that you will soon be back at Newcastle.

For blog readers wanting to know more about the MLitt programme, see the Children’s Literature Unit page on the Newcastle University website. Highlights of the Seven Stories Collections can be seen here.

In this blog post, PhD candidate Helen King feeds back on our recent workshop on creative approaches to academic writing.

Within CLUGG we to like vary our activities as much as possible, and jump at the chance to learn new skills and develop as researchers. On the 13th March we had the pleasure of a visit from Ann Coburn, a children’s and YA novelist and playwright who lectures in Creative Writing at Newcastle University and is an accredited Royal Literary Fund Fellow. Ann led us in a workshop on creative approaches to academic writing, using a variety of exercises to help us reflect on our work in progress.

Writing can be the hardest and also the most solitary part of a research process, requiring a balance of the methodical and the creative that is often hard to get right. Getting together to explore the writing process helped us dwell on the pleasure of the writing experience without the pressure of a looming deadline or set of criteria. This was also a challenge; as researchers we invest much of ourselves into our writing, and sharing our writing with a group required a certain level of vulnerability. Ann was good at getting each of us out of our comfort zones by tasking us with short bursts of writing without any planning, which we then shared with the group.

For one such activity, she handed rounded a bag of objects: an apple, coins, a bottle of water for instance. We were to choose something that could represent our work in progress (WIP, as you shall see written here), be it a PhD, Masters thesis, book or journal publication. We then wrote for 10 mins to explore why we felt drawn to that object as a analogy for our work. Here are some examples from three of us at CLUGG:

My work in progress is like a Danish kroner. It has value, both in the money it costs me to do and in the sentimental value it has in looking back at the same texts I used for my undergraduate dissertation and inspired my aspiration to be a researcher. Currency is passed from person to person and from pocket to pocket, accumulating more wear and marks as people exchange it. This is also what happens to research, as ideas are exchanged like currency. I borrow aspects of my research from the pockets of other researchers and hope to add to the wear and marks that they have made in my own use of it. The hole in the centre of the kroner is like the hole at the centre of my work in progress. The only difference between them is that the hole in the kroner is permanent, but the hole in my work is destined to be filled in.

My current WIP is a history of the Carnegie Medal. It’s like a pine cone, in that it has many small, individual parts, each of which is distinct, but which interlock to create a bigger thing. Unlike a pine cone, though, all the individual parts are quite different in size and shape – it’s not neat and regular. As with a pine cone, though, once you start pulling all those bits apart to look at them more closely, it’s really hard to fit them neatly back together again!

My WIP is like an onion because, to paraphrase the great poet Shrek, it has layers. And sometimes it stinks, and makes you cry. This PhD feels more vulnerable and personal than I think I had ever imagined it would. If it has layers, then my research is currently in the outer layers. This means that I don’t know what I’m going to find. I can guess – and the more I look the better my guesses get, but I am not going to know until I get in there with a good sharp knife. These outers layers, be it ‘children’s literary criticism’ or ‘reader response theory’ or ‘critical race theory’, have to be got through before I can get to the more specific details, the details that are really mine. And like an onion, what it needs is patience. You can’t expect to blast it over a gas flame for 3 mins and not have a charred mess. It needs time, low heat and a lot of butter.

In doing this exercise, we were surprised at how it revealed new ways of thinking about our research. For a few of us, there was a realisation of how much one personally invests in academic research, whilst it helped others to reimagine their position as a researcher as being like one part of a greater dialogue that made up their field.

The rest of the session was spent drawing associations between opposing themes within our research, and then free writing using these associations as a trigger. Free writing involves writing continuously for a set period of time, without planning, and without any particular regard for spelling, sentence structure or content. We were all surprised at how this exercise allowed us to see connections that we had not been able to see before, and to tap into a more intuitive of way of thinking about out subject.

As well as being good fun and getting us out of out comfort zones, this session has given all of us tools that we will be able to draw on as we continue with our research. Thanks go to Ann Coburn for her expert leadership, and PhD candidate Lucy Stone for organising the session.

In the year leading up to my time in Newcastle as an MLitt student at the Children’s Literature Unit, people would inevitably say, upon hearing I was going to study children’s literature: ‘Oh I see, to learn how to write children’s books!’ I’d have to explain that studying children’s literature is in fact much the same as studying German literature and so that no, they weren’t talking to the next Roald Dahl. They’d be slightly disappointed by my answer and then would, full of hope for my future again, burst out, ‘Oh but I see, because that degree will much improve your prospects on the job market!’ Well, yeah but no. There’s not exactly that many jobs needing that qualification, but I’ve had the immense luck to find a job that suits my education perfectly.

I’m writing this blog post while seated in an enormous Boeing jet, waiting to take off in Brussels, Belgium (my home country), for Dubai, United Arab Emirates. You’ve just caught me in one of the busiest months in my ‘career’ so far, with the Frankfurt Book Fair, the Lakes International Comic Art Festival and the Sharjah Book Fair within three weeks of each other.

So what do I do and how did I get there? I work for an organisation called Flanders Literature, an autonomous government organisation that gets its funds from the Flemish Ministry of Culture. (In tiny Belgium you have Wallonia in the south, where people speak French, and Flanders in the north, where people speak Dutch. Then there’s the city of Brussels, which is an entity in itself and is officially bilingual. Lots of things, like education, culture, youth, health and so on, are the responsibilities of these regions and not of the federal government.)

Flanders Literature has a total of eighteen employees at the moment. In Flanders itself we issue grants to writers, illustrators, graphic novelists, playwrights and translators, so that they can ‘buy time’ to work on their books. The amount of these grants depends on the literary and artistic quality of their work, which is judged by advisory committees that are made up of experts in that particular genre (e.g. a writer, a bookseller, an academic).

About half of us are part of ‘the foreign department’, including myself. It’s our job to spread the word of the best literature from Flanders to foreign publishers, in the hopes of convincing them to translate and publish books by Flemish authors. You could say we do the work of an agent, but without the financial gain of sealing a deal (as we don’t own or sell any translation rights) and without the limitation of just a handful of authors. If it’s great and written or illustrated by someone from Flanders, we’ll promote it. And on top of that, we offer grants to help make the costly process of translating a book a little easier. There are a few other countries who have a similar system, like the Netherlands, Norway, Finland and Poland. You’ll notice these are mostly small languages who have to fight for their place in the international book world with different weapons than the English-speaking world.

So as Grants Manager for children’s literature and graphic novels I’m responsible for maintaining a network of foreign publishers, keeping them up to date on the books that might be of interest to them and helping them in every possible way to make it easier for them to translate and publish one of ‘our’ books. It means I get to read many books (and remembering the ending!) and have to bring across my enthusiasm for them to other people, i.e. foreign publishers.

An important part of my job is meeting as many foreign publishers as possible at a few book fairs we attend. Frankfurt (October), Bologna (March or April) and London (March or April) are very important each year. On top of that, there’s Angoulême for graphic novels and this year the Sharjah Book Fair. A first for me, and the second time for our managing director, who noticed there was a big demand for children’s books in the Arab world last year. I’m very excited to discover this whole new world!

And how did I get here? Well, pure luck. And a great boss. I’d been struggling to find a proper job for about eight months when there was a vacancy at Flanders Literature for a part-time temporary administrative job. Writing meeting reports, processing applications, that sort of thing.

Not my dream job, but with the foot in the door idea in mind I applied and got the job. And then someone got ill, and they asked me to start working full time. Temporarily. And then the Minister of Culture decided to get us extra money, and my boss promised me ‘a proper job for my qualifications’. And then the Ministry had to cut back on costs, so he had to take back that promise, but I could stay on. Temporarily at least. Until they ran out of money and they couldn’t keep me on. But perhaps – my boss asked me almost shyly – I could do the secretary’s work for a while until things changed? Temporarily, of course.

And things finally did change. Thanks to my boss and a wonderful team of co-workers I got the chance to grow, and after four years ended up where I am now. In a Boeing on its way to Dubai. Sometimes luck is on your side.

(Oh, and don’t forget to check out www.flandersliterature.be if you’d like to know more about our books and our organisation.)

We would like to invite you to visit our Children’s Literature Unit on Wednesday 7th February 2018 from 3:30 to 5:30pm, as part of Newcastle University’s Postgraduate Open Day.

If you’re considering an MLitt, MPhil or PhD, come along and find out about studying children’s literature or creative writing for children and young people in Newcastle. Meet current students and discuss your research project with potential supervisors, and find out more about our outstanding research collections with staff from Special Collections and Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books.

Register your attendance for the afternoon here. We look forward to meeting you soon. In the meantime, you might like to read about last year’s Open Day.

We would also like to invite you to the event We Come Apart with authors Sarah Crossan and Brian Conaghan, chaired by author and Teaching Fellow by Liz Flanagan. This event is free, and will be followed by a drinks reception and book signing. 6:30 – 8:00 pm. Find out more about the event and book your place here.

Jacqueline Ho, MLitt Student

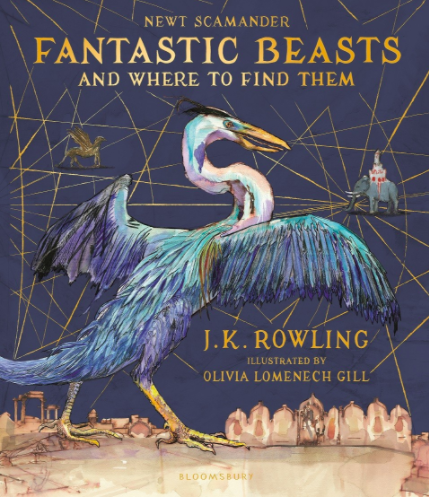

Who do you immediately think of when you hear Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them? J.K. Rowling? Eddie Redmayne? There is, however, someone else who is worth just as much praise – Olivia Lomenech Gill, illustrator of the latest edition of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Last week, I had the privilege to celebrate the book’s exclusive launch with Olivia at Seven Stories, a place I’ve longed to visit.

Stepping into the attic, I was completely mesmerised by the atmosphere: warm, welcoming, magical.

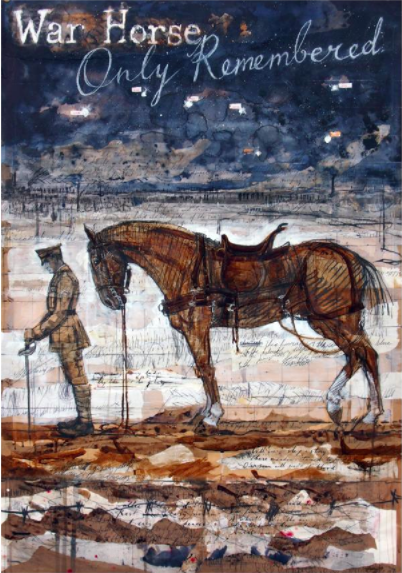

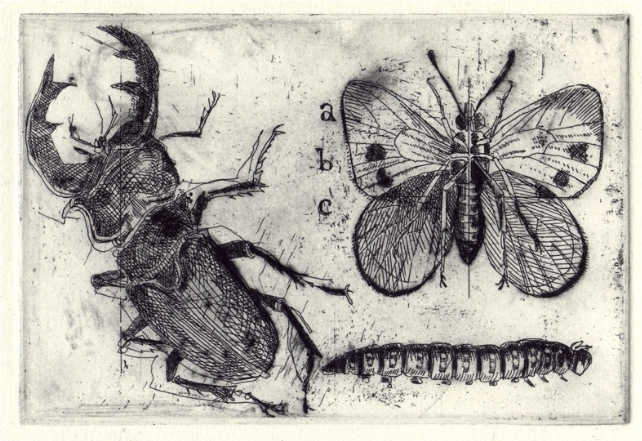

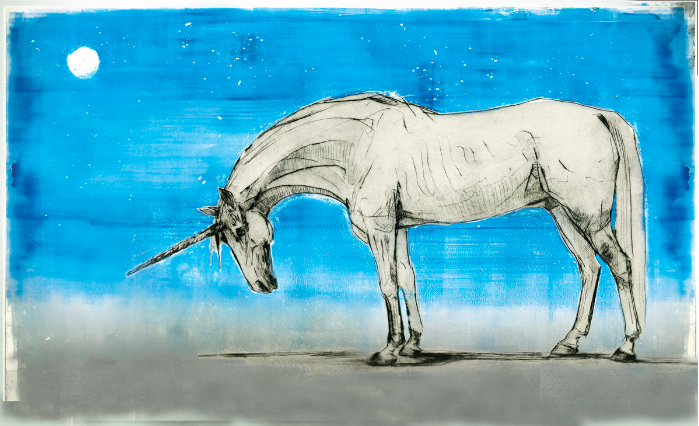

Olivia began her discussion on the creative process behind Fantastic Beasts by sharing one of her very first paintings, a horse, made when she was 6-years-old. Ever since, horses have become her long-term working partner. Before illustrating Fantastic Beasts, Olivia worked with Michael Morpurgo. Where My Wellies Take Me (2012) was her debut illustration project. She was then invited to draw pictures for War Horse. Here is one of them, Standing To:

After many years of working with horses, Olivia began on Fantastic Beasts, a rather challenging project. Taking roughly eighteen months to complete, Olivia began the project by studying and sketching animals from real-life and Greek Mythology. Some beasts pure products of Rowling’s imagination, Olivia found them difficult to create. Once she had tackled the beasts’ general appearance, Olivia sought to make the creatures believable to the readers, visiting zoos and studying special animal collections and archives.

Living in the generation of technology and social media, computer software like Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator are popular among many contemporary designers and artists. When illustrating creatures, many may also choose to take film footage of animals “in the field” for later use. Not Olivia. She prefers the traditional way: working in situ wherever she can with pencil, charcoal and sketchbook.

Olivia believes doing rough sketches by hand somehow helped her to develop an intimate relationship with animals, and thus aids her illustration work. She also makes animal models. For example, to develop her design of the Acromantula, she created a model of a spider-like insect in her studio.

Olivia’s studio also plays a great role in the illustration process. She designed and built her studio, a strong believer that architecture affects one’s working process. It attracts many creatures, such as birds and insects. At times disturbing and troublesome, Olivia was ultimately thankful for their presence throughout this project; it was fitting that in illustrating creatures some live ones should have been present.

What struck – and inspired – me most was Olivia’s modesty and honesty. This project had panicked her, she admitted. I’m not a good illustrator; my drawings aren’t good enough. On the contrary, Olivia truly is a fantastic illustrator. I empathise with her and see my own struggles as a researcher reflected in Olivia’s as an illustrator. Just as Olivia must spend lots of time “in the field” and make copious preparatory sketches, so in literary studies a researcher must spend lots of time in the library, reading, making notes, forming and employing the right methodology. But when it is something you love – as illustrating is for Olivia and researching for me – take courage, push on through the difficulties and moments of self doubt, do the best you can and you’ll be surprised at just how far you can go.

You can find further examples of Olivia’s illustrations on her website.

The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode Four

On realising I know nothing – but am starting to learn

There’s a rather lovely sense of back-to-school in Newcastle at the moment: there’s an autumnal chill in the air, the leaves are turning and I’ve bought some splendid new shoes.

It’s the start of the new academic year, and for me, as a research student, it’s also the end of the old one, which technically finished mid-September when I had to submit the third and last research assignment of my first year.

In one sense it seems like yesterday that I started the MLitt in children’s literature as a mature student; in another, it feels like a lifetime (largely in a good way). As mentioned in previous blogs, I’m taking the course over two years, as a part-time student, so this is essentially the half way point for me.

So what have I learned?

The first and possibly most important thing for me was not to underestimate just how much there is to learn: many years as a keen reader of children’s books are certainly not a passport to academic success. There’s a song by Dean Friedman from the 1970s where the chorus goes something like you can thank your lucky stars that we’re not as smart as we like to think we are. It’s not a track I ever particularly liked, but unfortunately it’s been going round and round in my head, almost since my first meeting with my supervisor, and certainly since I started getting feedback on my work. It turns out that academics can be – how can I put this? – blunt in asserting their opinion of one’s hard-sweated efforts, and any notion that I’d walk in being brilliant was quickly dispelled.

The second lesson was somewhat connected, in that it involved a growing appreciation that challenge and criticism is not only good in a ‘swallow-your-medicine’ kind of way, but that it can also be thoroughly enjoyable. It can be disconcerting at first to be forced to justify everything you say or write (at some points when asked why I’d included mention of a particular critic, for example, I just wanted to wail ‘well I don’t know, it just seemed a good thing to write’). But actually, being forced to anticipate that kind of challenge has made me much more stringent in my own writing, both in my academic and professional life.

And that’s probably the nub of the third lesson: academic writing is a skill in itself. Having been a journalist for almost three decades, freelance for half of that, I’m accustomed to writing for a variety of different audiences from the general public to policy-makers and specialists. Before I started this degree, I was aware that I’d have to abandon some of my most dearly-held tenets, such as never writing an introductory sentence of more than 30 words; I also knew that I’d have to get to grips with proper referencing. But I had thought less about other aspects of academic writing, from the simple (such as not using contractions) to the harder-to-judge, like avoiding colloquialisms. In each of the three research assignments I’ve submitted, I’ve been picked up for using informal language, even though I’ve tried very hard to stamp it out in my writing.

Has it been worth it? Well, I have to say I’ve absolutely loved it, challenges and all. It’s been possibly harder than I anticipated to balance my professional life and university life (not to mention life-life and all its inevitable issues), but it as also been hugely satisfying. I’ve genuinely had a sense of progression, not just because my marks have steadily grown higher over the course of the year, but because I can see myself that while my work still has an enormous way to go, it’s definitely improving. In case anyone’s interested, my research topics covered my existing interests – mid-twentieth century books for girls – but through a lens that was new to me, that is, the feminine middlebrow. The first essay was on career novels for girls, the second on the family novels of Noel Streatfeild, and the most recent on Mabel Esther Allan’s coming-of-age novels, specifically the Drina series (written under the name Jean Estoril).

So now it’s time to plan the dissertation – probably in itself the topic for another blog – and to jump in to my second and final year as a mature student. I’m looking forward to it very much – and did I mention I’ve got some great new shoes?

The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode Three

Making Connections: 20th-Century Style

When I was studying for my first degree in the 1980s, I knew just one person with a computer, a final-year PhD student. Unlike the rest of us (lecturers included) who were still wedded to paper and pen – he was able to commit his wise analysis of the works of Christina Rossetti straight onto hard disk.

Today, of course, it’s a very different story: looking round the seminar room, the majority of students are tapping away on tablets or laptops, with only the occasional diehard making use of an actual paper notebook as opposed to a computerised one.

The MLitt in Children’s Literature, for which I’m studying as a mature student, is a research degree, largely involving one-to-one study and working on research essays with a supervisor. But learning about research methods is a requirement of the course, so we are obliged to study a module with the students who are undertaking the MA in English Literature – hence being in the seminar room with other postgraduates.

Learning about various aspects of research – such as how to formulate a dissertation topic and how to go about doing it – is obviously useful in itself, but for me, as a mature student, the best thing about doing this module has been the opportunity to meet other postgraduates on a sustained basis. This has been good socially – I was hugely heartened after the first seminar to be invited for a drink with a couple of other mature students – but also academically. As the first year has progressed, the MA group has coalesced into a largely friendly peer-support network, setting up a Facebook group to answer each other’s last-minute panics and queries, and regularly meeting up in person to share works-in-progress, or just to let off steam.

Being an MLitt student, I’m in an insider-outsider position with this group, especially as I’m still based at home in Scotland most of time. But I’ve appreciated the opportunities (in class and out) to discuss ideas, talk about dissertation or essay intentions, and get input and fresh ideas from people with very different research interests to me (artificial intelligence, post 9/11 fiction, and digital apps, to name but a few). It’s also been rather nice to get the odd invitation via Facebook to student house parties – not something I thought would be happening at the age of 50.

Widespread use of mobile devices (my laptop seems practically archaic by contrast), and social media apart, the actual process of academic study and research has also undergone a technological revolution in the last 30 years. I remember learning to use microfiche to read archived copies of newspapers, and very fiddly it was too, but that was as good as it got; e-readers were the stuff of Tomorrow’s World, and journals and books were shelved on, well, actual shelves. Thinking about it, it’s absolutely amazing today to be able to gain access to such tremendous amounts of information without even having to make a physical trip to the library – in effect, you have a library in your hands.

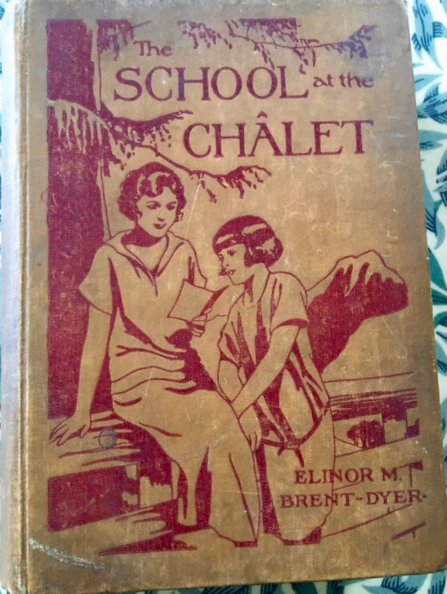

Then again, sometimes the old ways can have benefits: just as attending the research methods seminars has led to valuable social and academic relationships, actually visiting the library can bring its own advantages. This was brought home to me in one of the earlier seminars, which included teaching about the university’s special collections and took place in the library itself. Sitting waiting for class to start, I idly turned over a letter that had been left on the table in front of me.

Wait, surely that wasn’t H.G. Wells’ signature?

Indeed it was. This was one a number of objects that library staff had strewn about to entice us – others included material from the Bloodaxe archive, and (most excitingly for me) an early edition of one of my favourite books, Elinor M. Brent-Dyer’s The School at the Chalet. Lifting it up, feeling its heft, and smelling its smell, I felt a connection that stretched back to the first half of the last century – even the fastest broadband can’t beat that.