Further particulars

The awards recognise both David Almond’s contribution to children’s literature and his connections with these partner institutions: he is a patron of Seven Stories and an honorary graduate of Newcastle University.

The Fellowships aim to promote high-quality research in the Seven Stories collections that will call attention to their breadth and scholarly potential. The two awards of £300 each are to facilitate a research visit to the Seven Stories collections in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK of at least two days by a bona fide researcher working on a relevant project. Applications will be considered from candidates in any academic discipline. The successful applicants will have a clearly defined project that will benefit from having access to the Seven Stories collections (please see indicative information about the collections below). All applicants should consult the Seven Stories catalogue as part of preparing their applications. A well-developed dissemination strategy will be an advantage. Priority will be given to the importance of the project and best use of the Seven Stories collections as judged by a senior member of the Children’s Literature Unit in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics at Newcastle University and a senior member of the Collections team at Seven Stories.

Some previous David Almond Fellows have gone on to take up fully-funded PhD studentships at Newcastle University, others have disseminated their research into the collection through book chapters, peer-reviewed journals and conference papers. One of our former Fellows said of her visit that it was ‘a wonderful opportunity to work in the archive of Seven Stories… it is undoubtedly an invaluable asset for researchers internationally, and something the city can be extremely proud of.’

Eligibility for the award

Applicants must hold a first degree or higher from a recognised institution of higher education.

Note: non-EEA applicants are reminded that to take up a Fellowship they must hold an appropriate visa. Neither Newcastle University nor Seven Stories can help with this process. Please see the UK visas website for more information.

Responsibilities

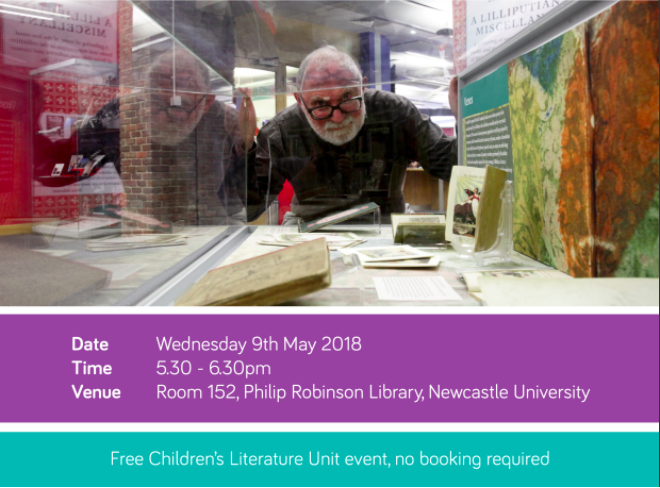

Fellowships must be taken up before the end of December, 2018. Recipients are expected to spend at least two days in Newcastle and are encouraged to time their visits to enable them to participate in events organised jointly or separately by the Children’s Literature Unit and Seven Stories. (Please note: successful applicants must contact Seven Stories and agree a date for the visit prior to making travel arrangements; normally a minimum of two weeks’ notice is required before any research visit.) Acknowledgement of the Fellowships must accompany all dissemination activities arising from the research.

The Seven Stories Collection

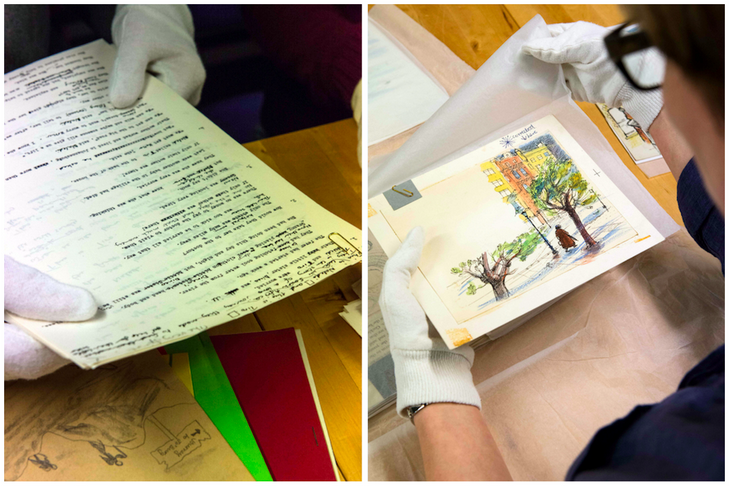

Seven Stories is the only accredited museum specialising in children’s books in the UK. Its collections are a unique resource for original research, particularly insofar as they document aspects of the creation, publication and reception of books for children from the 1930s to the present day. The steadily growing archive contains material from over 250 authors, illustrators, editors, and others involved in the children’s publishing industry in Britain.

Researching the Seven Stories collection could enhance a number of research topics. Examples of research areas and relevant collections:

Makers of children’s literature: children’s book history 1750-2000

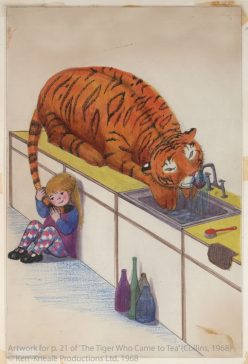

Children’s books have been under-represented in book history scholarship. Seven Stories’ holdings can be used to investigate the forces which have shaped the children’s book. Areas of interest include editing and publishing, education and bookselling, diversity and race and changing technologies. Key archival holdings include the David Fickling Collection, the Aidan and Nancy Chambers / Thimble Press Collection, and the Leila Berg Collection. The recently catalogued Noel Streatfeild Collection also provides fascinating insights into the life and times of a leading children’s author during the mid- twentieth century.

New adults: the growth of teenage literature

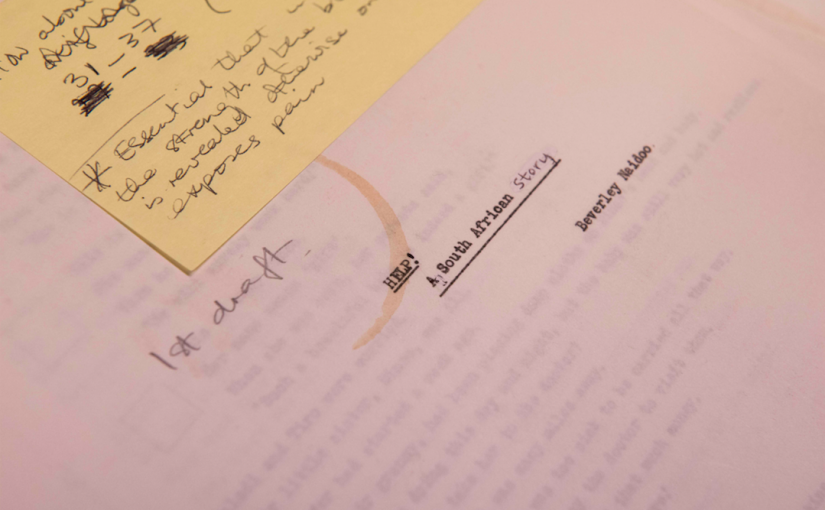

Seven Stories’ holdings represent the opportunity to investigate the development of teenage literature from a number of perspectives: holdings include detailed evidence of the process of composition from early draft to published text; evidence of socio-political contexts, and evidence of the publishing contexts. Key archival holdings include the Aidan and Nancy Chambers / Thimble Press Collection, the Diana Wynne Jones Collection, the Philip Pullman Collection, the Beverley Naidoo Collection, and the Geoffrey Trease Collection.

Inclusion and diversity

Seven Stories is particularly interested in supporting studies which explore themes of inclusion and diversity within our archives: race and heritage, disability, gender and gender identity, sexual orientation, age, socio-economic status, religion and culture. Projects in this research field might be cross-cutting, looking at a number of different archives within the Seven Stories Collection.

Children on stage: twentieth century children’s theatre

Seven Stories holds the complete archive of David Wood, one of the most prolific and influential playwrights for children in Britain. Projects based in this archive may approach the topic of children’s theatre from a number of perspectives, including theatre history and adaptation. Other relevant holdings include the Michael Morpurgo Collection and the recently acquired David Almond Collection.

More information can be found on the Collection pages of the Seven Stories website. Most of the artwork and manuscript collections are fully catalogued*, and the catalogues can be searched online via the link provided on the website. A list of many of the authors and illustrators represented in the collection can also be found on the Collection pages.

(NB this is not a complete list of the collections).

Please see also the Seven Stories Collection Blog, containing a variety articles describing or inspired by the Collection.

Application process

Applicants are asked to submit the following items by 1 June 2018:

- an application form

- a curriculum vitae

- a brief proposal (of 1,000 words maximum)

- one confidential letter of recommendation (sealed and signed; confidential letters may be included in your application packet or recommenders may send them directly)

Applications may be submitted by email or post.

Email: Kim.Reynolds@ncl.ac.uk

Post: David Almond Fellowships, School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK

* NB Thanks to a major accrual, recently received, cataloguing of the David Almond archive is ongoing – the records are expected to be online by 30 June. An interim listing is available on request. Please contact collections@sevenstories.org.uk

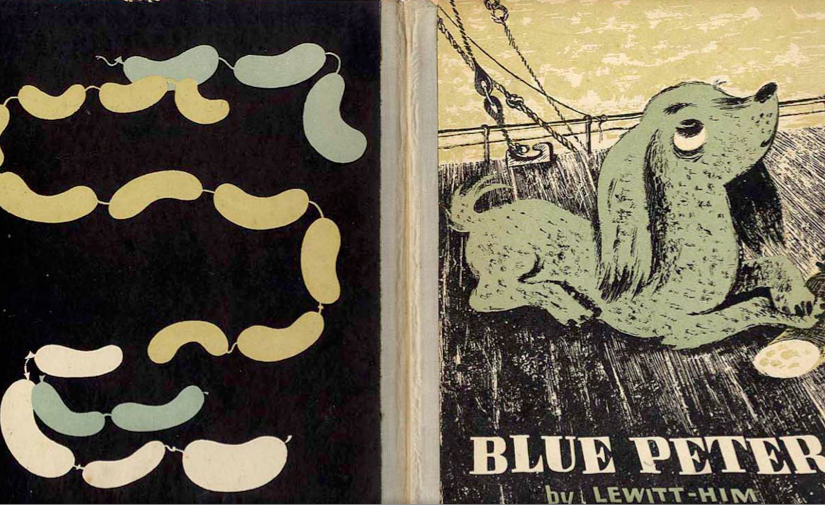

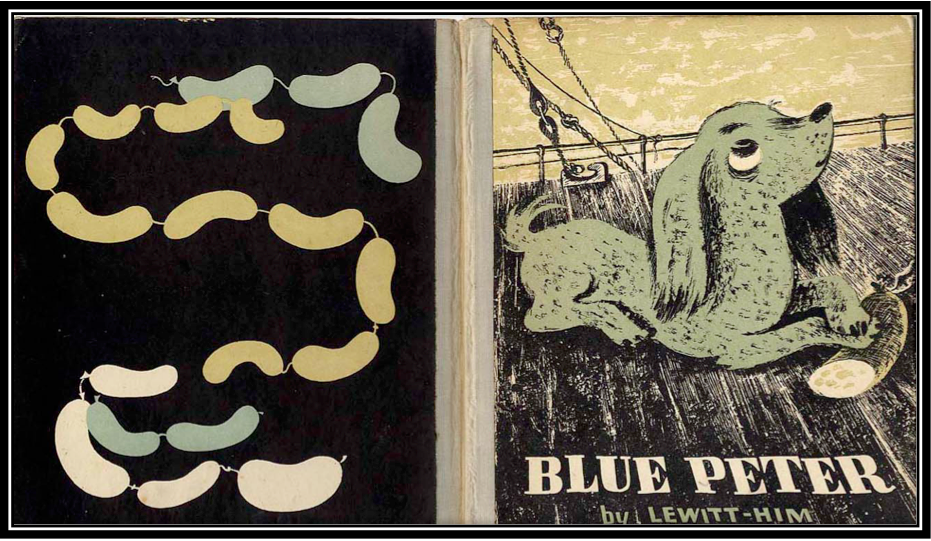

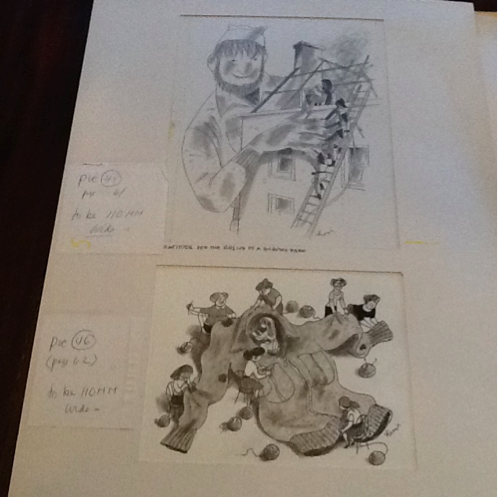

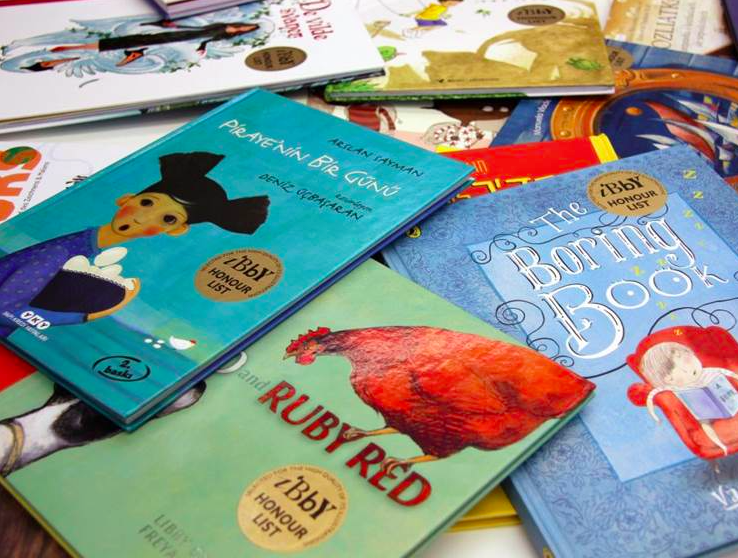

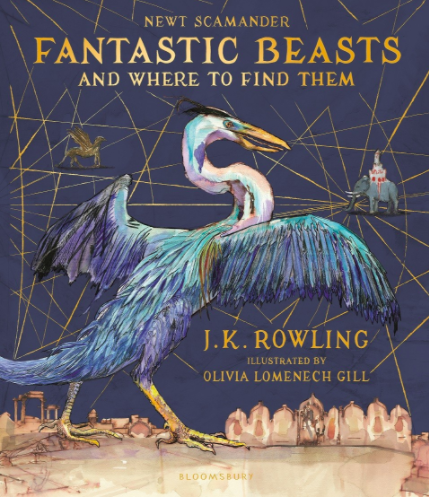

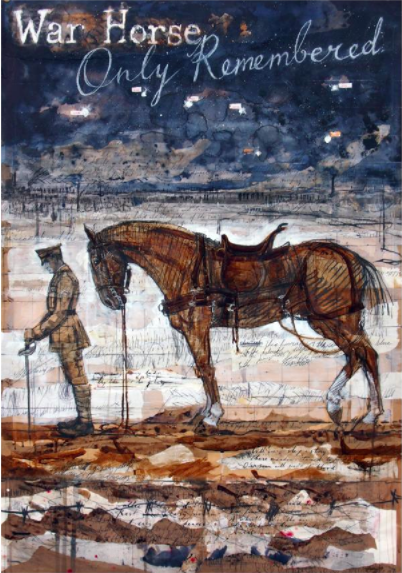

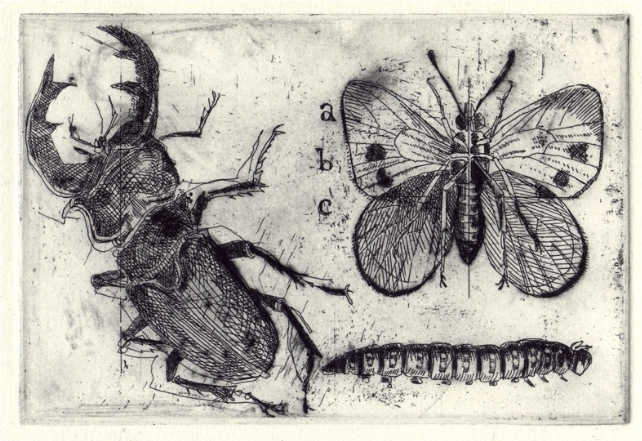

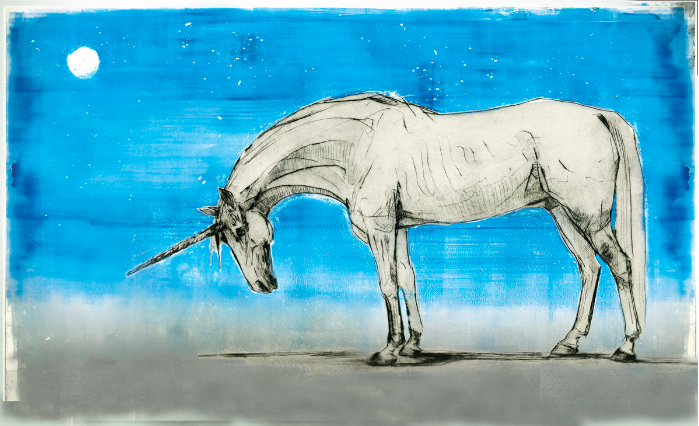

Images from Seven Stories: The National Centre for Children’s Books, photography by Damien Wootten.

The staff at Seven Stories were wonderful and Kris McKie was brilliant at introducing me to the David Wood collection. On learning that I planned to look at material related to six productions, he subtly hinted that I might not quite get through all thirteen archive boxes in the time available. On his suggestion, I started with the boxes related to David Wood’s adaptation of Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958), which kept me busily occupied. I have written more extensively about the work I did there for the Seven Stories Collection Blog (coming soon!). The material related to this adaptation and to many others is incredibly rich and it has provided me with a range of questions and perspectives to consider. Just as a tantalising nugget – I am sure that you are aware of the controversy over casting choices for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child but were you aware of the colour-blind casting for the premier of Tom’s Midnight Garden (Unicorn, 2000)?

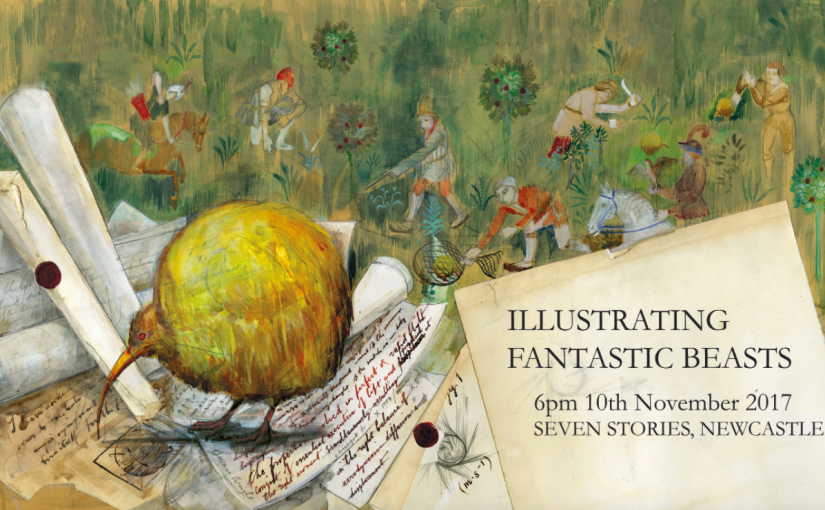

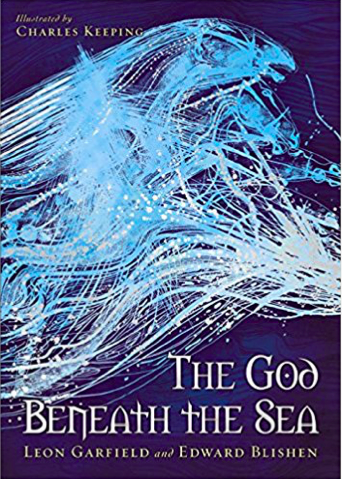

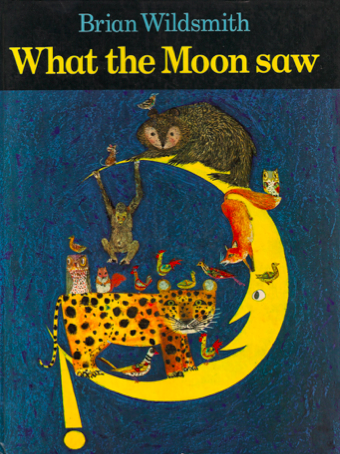

The staff at Seven Stories were wonderful and Kris McKie was brilliant at introducing me to the David Wood collection. On learning that I planned to look at material related to six productions, he subtly hinted that I might not quite get through all thirteen archive boxes in the time available. On his suggestion, I started with the boxes related to David Wood’s adaptation of Philippa Pearce’s Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958), which kept me busily occupied. I have written more extensively about the work I did there for the Seven Stories Collection Blog (coming soon!). The material related to this adaptation and to many others is incredibly rich and it has provided me with a range of questions and perspectives to consider. Just as a tantalising nugget – I am sure that you are aware of the controversy over casting choices for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child but were you aware of the colour-blind casting for the premier of Tom’s Midnight Garden (Unicorn, 2000)? As an author, reviewer, collector and translator of children’s literature, Brian Alderson is perhaps one of the founding figures of the children’s literature community. Therefore, it was lovely to be able to sit back and listen to him speak about a handful of children’s authors and illustrators that I was either unaware of or who I want to know better. The talk was given in honour of the

As an author, reviewer, collector and translator of children’s literature, Brian Alderson is perhaps one of the founding figures of the children’s literature community. Therefore, it was lovely to be able to sit back and listen to him speak about a handful of children’s authors and illustrators that I was either unaware of or who I want to know better. The talk was given in honour of the  I vividly remember pouring over their illustrations as a child. Needless to say, several of the picturebooks that Brain Alderson shared with us are currently winging their way towards me through the post!

I vividly remember pouring over their illustrations as a child. Needless to say, several of the picturebooks that Brain Alderson shared with us are currently winging their way towards me through the post!