What impact does alcohol marketing have on young people? Our newest Idea for an Incoming Government is from Professor Eileen Kaner and Dr Stephanie Scott (Institute of Health and Society), who call for restrictions to be put in place, protecting our national health, and improving young lives.

What is the problem?

Alcohol use is the leading risk to health and well-being in young people, accounting for seven percent of disability adjusted life years in 10-24 year olds globally, with UK adolescents amongst the heaviest drinkers in Europe. Frequent, often high-intensity drinking in early to mid-adolescence has been linked to a myriad of adverse effects. Short-term implications, which pose the greater immediate risk, include accidents; early and unprotected sex; exacerbation of mental health problems; and poor school attendance and reduced educational attainment. Acute problems may have life-time consequences, such as early disfigurement or unintended pregnancies. Moreover, the longer and heavier an individual drinks, the greater the risk of developing chronic health problems such as liver disease or cancers later in life.

As a caring society, we should do more to limit youth exposure to alcohol marketing. But how can we be sure that there is a connection between this and alcohol misuse?

A growing body of literature, including two recent systematic reviews (Anderson et al, 2009; Smith and Foxcroft, 2009), demonstrates an association between exposure to alcohol marketing and initiation or progression of alcohol use, as well as development of pro-drinking attitudes and social norms (Gordon et al, 2010; Lin et al, 2013). UK research suggests that alcohol brand recognition is common amongst young people as young as 10-11 years old (Alcohol Concern, 2012) with US studies demonstrating identification with desirable images in alcohol advertising in 8-9 year olds and brand-specific consumption in 13-20 year olds (Austin et al, 2006; Siegel et al, 2013).

Despite the heavy attention paid to price and traditional advertising, alcohol marketing is much more extensive and comprises price, product (image/branding), promotion (including advertising) and placement (point of sale and outlet density or distribution), defined as the ‘4 Ps’ or ‘marketing mix’. This means that availability as well as how a product looks or tastes can be of as much importance as how much it costs. The extensive nature of alcohol advertising, including through new media (e.g. sponsorship of social networking sites) means that young people are regularly exposed to alcohol promotion including many who are below the legal age to purchase alcohol.

A recent qualitative study in North East England among 14-17 year olds found that marketing seemed to play a key role in building recognisable imagery linked to alcohol products, as well as associations and expectancies related to drinking (e.g. having fun, drinking games, brand slogans or logos, drinks associated with certain TV shows, such as cocktails).

The solution

- Restrict alcohol advertising in newspapers and other adult press, with content limited to factual information about brand, product strength and provenance, mirroring The Loi Evin model in France.

- Establish an independent body to regulate alcohol promotion in the interests of public health/safety.

- Review the use of new media to market alcohol with a view to limiting the exposure of ‘under age’ young people who frequently access key sites (e.g. Twitter, Facebook etc.).

The evidence

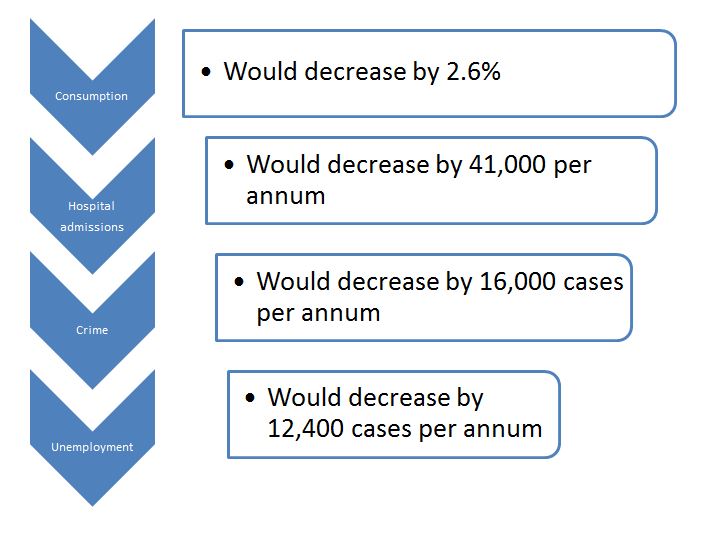

In terms of price restrictions only, recent research conducted in Canada over the course of eight years (where a minimum unit price has been implemented) suggests that a 10% increase in the price of most drinks led to a 32% fall in alcohol-related deaths (Stockwell et al, 2013). This international evidence is supported by UK modelling work which demonstrates the effects that setting a minimum unit price of 40p would result in (see below).

It is increasingly accepted that a fully joined-up public health response to tackle alcohol problems needs to include policy-focused interventions as well as individual-level input from health and social care practitioners (NICE, 2010). Individual and policy-level interventions are needed which can limit youth exposure to alcohol marketing whilst not curtailing producers’ legitimate right to market their products to adults.

Tweet @Social_Renewal using #Ideas4anIncomingGovt to join in the conversation.