A north east listening project

On the radio and online we are witnessing renewed concern to record local memories of cherished landscapes before they are lost forever. Examples of how this can be done include the BBC Listening Project and the National Trust Sounds of our Shores – a crowd-funded sound-map of people’s favourite seaside sounds. These examples build on classic Mass Observation recordings of everyday life (1937-1970) – notably Pub Conversations.

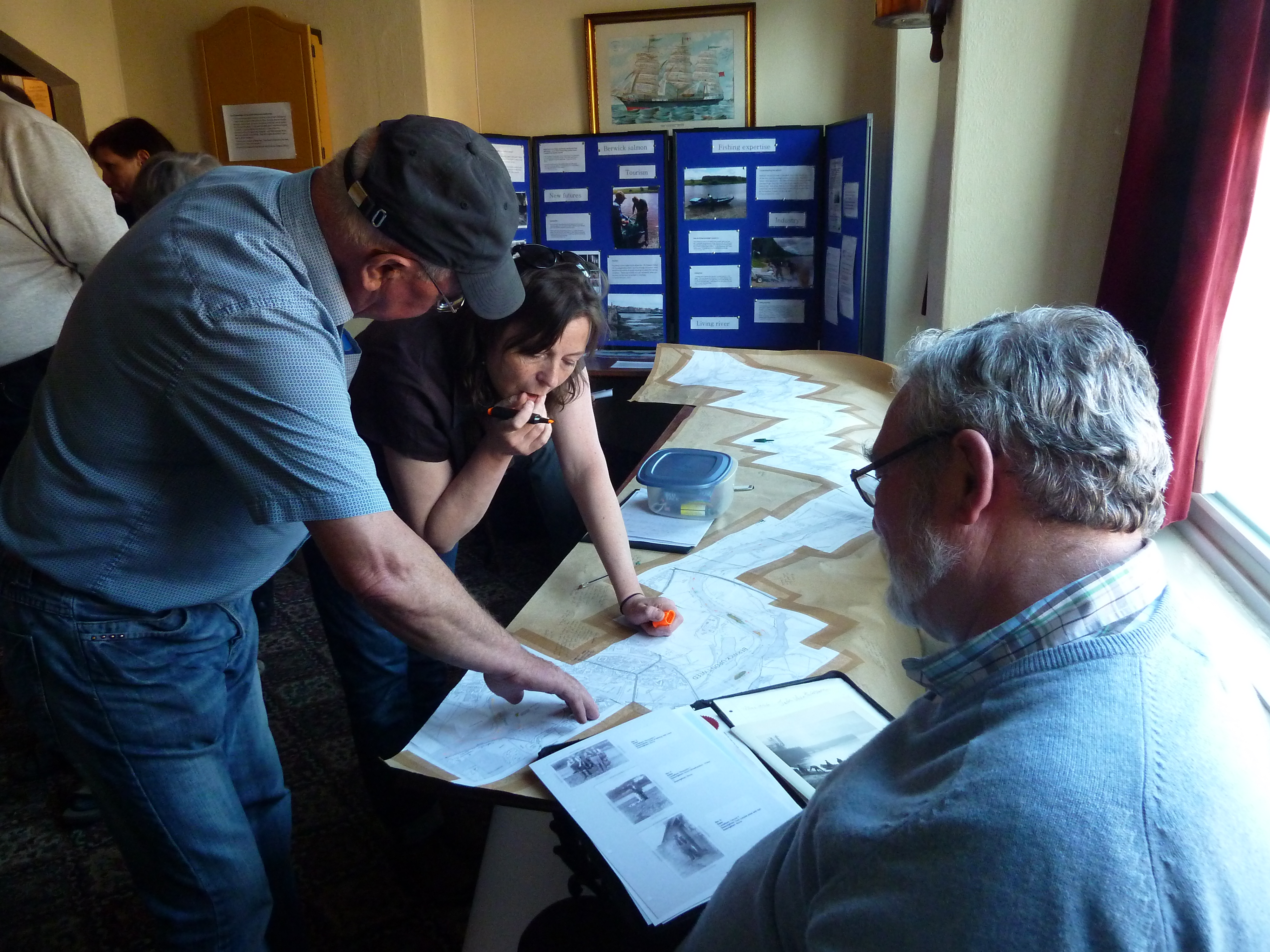

Inspired by this approach, Dr Helen Jarvis and postgraduate student Tessa Holland (both from the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology) are collecting impressions of the once-thriving salmon fishing industry in Berwick upon Tweed; both to stimulate public debate on this disappearing livelihood, and to record the wealth of local knowledge involved.

The project involves a series of ‘pop-up’ citizen-led story-telling events that coincide with the town celebrating 900 years of history, with collaboration from fishing communities and local history experts representing Our Families (a Berwick Record Office, Heritage Lottery funded project for Berwick 900). Participating in a summer of fishing-related feasts and festivals, including the crowning of the Salmon Queen, offers the ideal opportunity to raise awareness of the issues at stake.

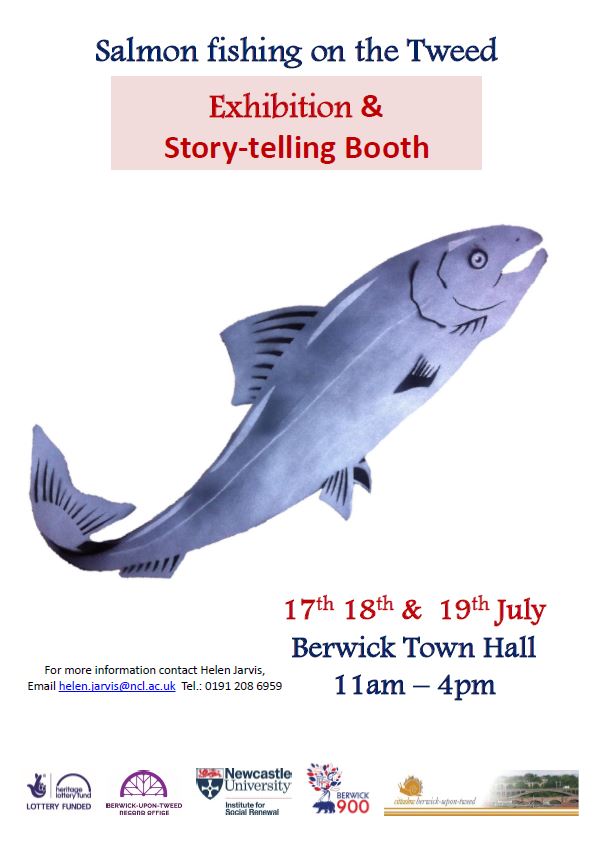

The salmon fishing project moves to Berwick Town Hall, with a storytelling booth, from 17th to 19th July. After this time the exhibition will be held at the Watchtower Gallery until August 16th.

Salmon fishing on the Tweed

Written accounts of net fishing on the Tweed exist from the 1200s, but the skills and knowledge of the river date back to before records began. Net and coble fishing is a traditional way of life which made Berwick-upon-Tweed famous and the industry once provided jobs for around 800 local people. The local significance of the industry is captured in pictures and memories of customs such as ‘blessing the salmon’ at the opening of the Tweed salmon netting season, midnight on 14th February. The vicar of Norham ended the custom in 1987 when the fishery in his parish closed.

Blessing the salmon, 1946, by permission of Berwick Record Office.

Loss of the nets

Chronic disinvestment and loss of the nets began in the 1980s, when many of the fisheries were bought out and closed down. Indeed, this experience – of close-knit community ties and generations of fishing expertise dismantled at a stroke – resonates with text-book accounts of deindustrialisation in heavy industries such as coal and steel. In each case, powerful commercial and political interests claimed economic competitiveness and new technology as motivation for consigning ‘outmoded’ industries to the past.

Since the Tweed Act of 1857 the right to catch and sell wild Tweed salmon is only held by net fisheries; rod-caught salmon cannot be sold commercially, so without the nets, there is no legal source for the wider, non-angling public. The rights to work these dormant fisheries are now held by the Tweed Foundation. Only two net fisheries remain active today – one at Paxton, and one at Gardo (near Berwick Old Bridge). The Paxton fishery now works in partnership with the Tweed Foundation to fish only for educational and scientific purposes. This explains why, despite the undisputed potential for a premium brand of locally caught wild salmon to put Berwick on the map, none is available to buy at the fishmonger or eat in local restaurants. The irony is that Berwick is closely identified with ‘slow food’ and ‘slow living’ civic organisations that promote locally produced, sustainable food and cultural heritage.

Prospects for renewal?

Despite its decline, powerful local attachments to salmon fishing traditions continue to shape the cultural heritage and landscape of this market town. From stories recorded so far, we learn that, in the past ‘thousands of people would go to watch the netting of the salmon – all through the season’ and this made the river a site of spectacle. This hints at some of the non-economic benefits that have been undermined by loss of the nets.

It is too early to report on the impact that public dialogue might have in reviving the last remaining fishing stations – and it is beyond the current scope of the project to make policy recommendations. But it is provocative to consider novel examples of government policy for small towns, like Berwick, which need to attract and retain residents, jobs and tourist income. In France, the government subsidises cafés that provide music and entertainment, justifying this by the combined stimulus to jobs and spending in public spaces – that in turn foster a convivial public life (Banerjee 2001). Is it far-fetched in this context to regard net fishing as a form of entertainment?

Dr Helen Jarvis, School of Geography, Politics and Sociology