In the Newcastle University public lecture on New Voices in Social Renewal, Dr Michael Price presented his work on big bonuses and managerial rewards, connecting them to inequality and social immobility. In this blog post, Dr Price and his colleague Dr Ewan Mackenzie, both from the Strategy, Organisations and Society research group in Newcastle University Business School, argue that it’s time to intervene to stop spiralling inequalities in our country.

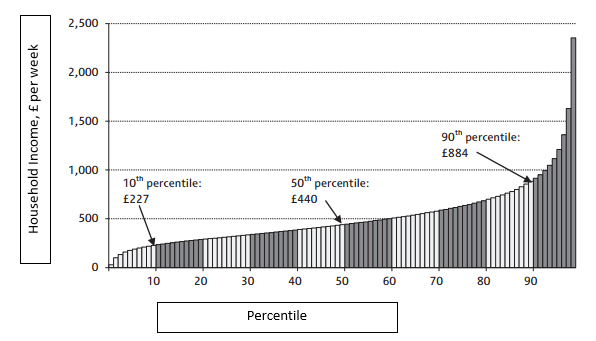

The gap between UK average pay and the pay of top executives is rising[1]. Despite government rhetoric about the British population “all being in this together”[2] the pay growth for those at the top of British society has dwarfed that of the rest of the population. Globally the issue is so pronounced that the World Economic Forum noted, in its 2015 outlook briefing, that income disparity is the most important risk to economic and political security[3] for the world today.

Research from the London School of Economics suggests the UK has one of the lowest rates of social mobility in the world[4]. Despite this there is a commonly held belief that paying for performance based on ‘merit’ is perfectly acceptable, after all, if people work hard and produce rewards for others as a result of their talents, why shouldn’t they share proportionally in the fruits of that labour? Such a position is deeply rooted in the philosophical notions of justice and desert[5]. In modern ‘liberal’ societies a conventional assumption is that a person should be rewarded in proportion to the discretionary effort involved. Associated notions of ‘social mobility’ have also been central to social and economic discourses since the early 1980s. In the UK, it is not hard to find well-trodden examples of people that have come from relatively modest backgrounds and elevated themselves, through supposed hard work, ingenuity and intelligence. Alan Sugar and his apprentices are broadcast onto TV screens every week, reinforcing the narrative of the “bootstrap boys”[6]. What is commonly perceived as worthy of merit is derived from the impartiality of the idea that one’s capabilities plus effort equals merit[7]. The propagation of this mode of reasoning has come to govern popular thought in 21st-century Britain.

Michael Young’s 1958 dystopia, The Rise of the Meritocracy, warned that pursuing a meritocratic agenda would perpetuate social inequality. Mike Savage recently confirmed this prediction in his Great British Class Survey, which suggested increasing social polarisation in British society. Savage characterises the ‘invisible’ bottom 15% of the British population as ‘the precariat’. Yet perhaps what is of equal alarm is the spiralling remuneration of ‘the elite’. Savage’s classifies the ‘elite’ as representing 6% of the population. He suggests they possess economic capital in property, savings and incomes which sets them apart from other classes[8]. Research has also indicated that managerial salaries are a significant driver of these trends, therefore highlighting the contribution of excessive reward towards spiralling inequality[9].

French academic Thomas Piketty suggests the “stratospheric pay of super managers” has come about because of a form of “meritocratic extremism”[10] prevalent in ‘liberal’ societies. This denotes the belief that ‘winners’ should be disproportionately rewarded to encourage a condition of envy, thus creating standards for others to strive towards. In a speech to the Centre for Policy studies, Boris Johnson claims inequality is essential for “the spirit of envy and keeping up with the Joneses, that is, like greed, a valuable spur to economic activity”[11]. Therefore it seems that notions of business ‘meritocracy’ are in vogue. Apparent equality of opportunity, has developed into a strong justification for increasing levels of remuneration and spiralling inequality.

Research being conducted here at Newcastle University has examined the genesis of these changes. One strand has investigated the influential 1995 Greenbury Committee[12]. This committee and their recommendations are important because they played a central role in constructing the current framework for remuneration policy in UK organisations. The stated position of the committee, with 20 years’ hindsight, is that the consequences of their reforms contributed to, rather than limited, the growth in top executive pay. The observation that many of the committee were likely to be affected by its findings, due to their positions as executives of large companies, is a rather obvious criticism. For instance, the refusal of John Monks, General Secretary of the Trade Union Congress, to participate, perhaps amplifies those criticisms.

The recommendations of the Greenbury committee facilitated the increasing use of performance-related pay schemes which often generate excessive and disproportionate rewards. Research investigating top executive pay and performance points towards a weak correlation with labour, yet these studies receive very little exposure outside of academic circles. Is it time for politicians to take heed of the warning signs, and substantively intervene on these issues, in order to take responsibility for the spiralling inequalities of our present?

Michael Price and Ewan Mackenzie

[1] Manifest/MM&K Executive Director Total Remuneration Survey 2013.

[2] David Cameron famously introduced this slogan in his 2009 speech to the Tory party conference http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=154

[3]See: http://reports.weforum.org/outlook-global-agenda-2015/top-10-trends-of-2015/1-deepening-income-inequality/

[4] See: http://cee.lse.ac.uk/cee%20dps/ceedp111.pdf

[5] See John Rawls 1970 work – A theory of justice.

[6] A bootstrap boy is representative of a generation of business leaders who ‘pulled themselves up by their bootstraps’ to lofty status in British business. See Kerr & Robinson (2010).

[7] Antony Sampson proposed this equation in his 1965 work, “Anatomy of Britain Today”

[8] Mike Savage is Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics. Along with Niall Cunningham, Fiona Devine, Sam Friedman, Danial Laurison, Lisa McKenzie, Andrew Miles, Helen Snee and Paul Wakeling, they’ve recently published a ground breaking study of social class entitled, “Social Class in the 21st Century”.

[9] Lemieux, T., Macleod, W. B., and Parent, D. (2009). ‘Performance related pay and wage inequality’. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1).

[10] See Piketty (2014) page 416.

[11] See: http://www.cps.org.uk/events/q/date/2013/11/27/the-2013-margaret-thatcher-lecture-boris-johnson/

[12] The Full report can be found here: http://www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/greenbury.pdf