Dr Peter Kellett is an architect and social anthropologist and Senior Lecturer in the School of Architecture Planning and Landscape. In 2013 he went to Ethiopia as a VSO volunteer working as Visiting Professor at Addis Ababa University on a capacity building programme. He returned in 2015 to continue work on collaborative research projects with his Ethiopian colleagues. Whilst in the country he collected numerous objects and images which form the basis of a series of exhibitions. Here he writes about the current exhibition in Bath which is supported by a grant from the Newcastle Institute of Social Renewal.

Fairfield House is a well-proportioned, Italianate mid-nineteenth century house on the outskirts of the genteel and historic city of Bath – and a long way from Africa. However for 5 years (1936-1941) it was the home of the Ethiopian Emperor, King of Kings, Conquering Lion of Judah, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I. Ethiopia was the only country in Africa country not to be colonised by the European powers and remained a proudly independent state – until Mussolini’s troops invaded in 1935. Haile Selassie, his family and his court managed to escape into exile – and ended up in Fairfield House. On his return to Ethiopia he gifted the house to the city of Bath, and it is now a multi-cultural centre and the base of numerous black and ethnic minority groups, including Ethiopian, African-Caribbean and Rastafari communities in the South West.

The window of Haile Selassie’s former bedroom is transformed into the Ethiopian flag assembled from hundreds of children’s sandals.

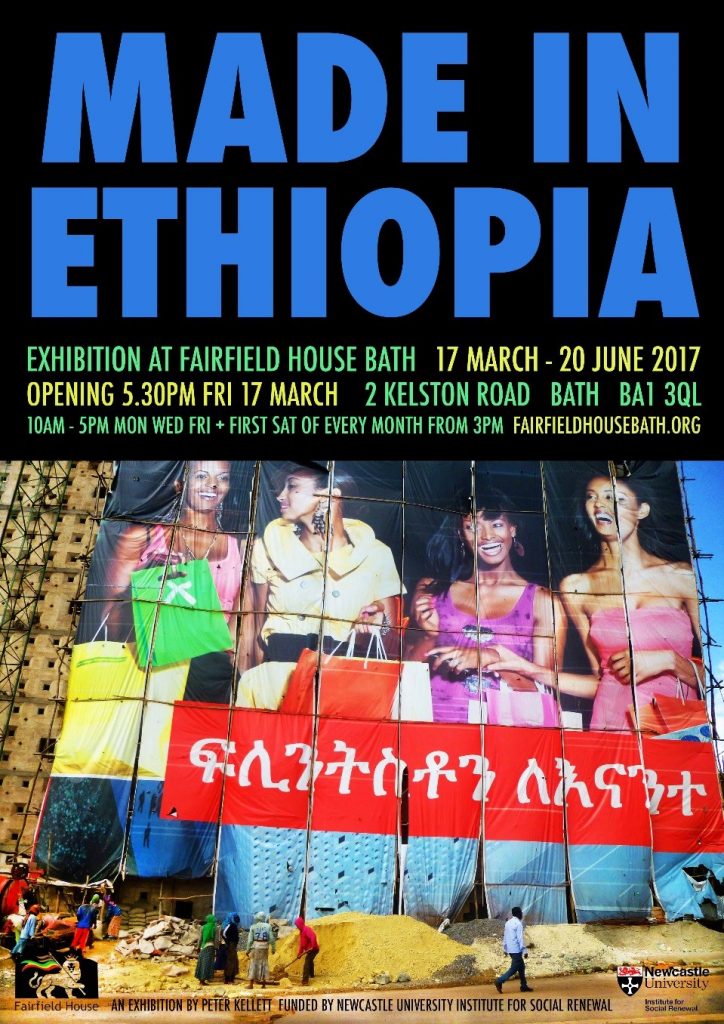

Given its rich history and ongoing links with Africa, Fairfield House is the perfect place for this exhibition which highlights processes of rapid socio-economic change and modernization in Ethiopia. Many aspects of these changes can be observed in the ordinary objects which people use in their everyday lives and which are visible and tangible manifestations of the move from handmade, locally-sourced, natural materials – towards machine-made, high energy, imported materials. These changes are impacting on how people live and work, as well as on the values which underpin the society.

The exhibition examines these changes through a focus on material culture. Objects are good for telling stories and focusing ideas. Drawing on contemporary art techniques, I created a series of assemblages of objects which present stories of celebration, optimism and creativity alongside development dilemmas and challenges. The installations are complemented by colourful video images on large monitors which show the objects in context. The key themes are food security, water, childhood, maternal health, language and religious traditions.

The exhibition commenced in March with a wonderful opening evening which drew people from numerous community, charity and religious groups from the South West. In addition to a few speeches, we enjoyed music played by an Ethiopian cellist and drank cups of traditional Ethiopian coffee poured from elegant ceramic coffee pots and listened to inspirational Rastafarian poetry.

Last weekend I returned to Fairfield as the house and exhibition were included in the Bath Newbridge Arts Trail. Over two days close to 150 people from many walks of life came to see the exhibition – and it was encouraging to see visitors attracted and curious about the vibrant displays which in turn prompted discussions and an interest in learning more about the issues presented.

On Saturday evening the house reverberated with the hypnotic rhythms of Rastafari drumming and chanting. The Rastafari meet regularly in Fairfield to celebrate the Sabbath and this was a special occasion to mark the anniversary of Haile Selassie’s triumphant return to Addis Ababa in May 1941 – to continue ruling as the last monarch of the 3,000 year old Solomonic dynasty which began with the union of King Solomon of Israel and the Queen of Sheba (ancient Ethiopia and Yemen). The Rastafari take their name from Haile Selassie’s pre-coronation name of Ras (Prince) Tafari, and for them he is much more than a king – he is regarded as God (Jah) and the messiah who came to liberate black people throughout the world. For them to spend time in his former house is highly significant.

The exhibition provides a focus for related workshops and participatory events to engage wider audiences. Starting with a lively session with the black and ethnic minority senior citizen group which meets regularly in Fairfield, we are now organising activities with the local community as well as visits of local schoolchildren and African refugees. These events will encourage creative activities around development themes with the aim of fostering understanding and dialogue between different social and ethnic groups and thereby contribute to community cohesion and social renewal.

Dr Peter Kellett