In this blog post, Dr Will Reid shares his story of how he became a marine biologist and the inspiration that led him to his exciting career choice

Blue Planet II is well underway now and for many a marine biologist, like myself, it is an opportunity to say, “I work on those” and get a bit giddy with excitement. We have seen some wonderful footage of walruses, the graceful Ethereal snailfish and colourful coral polyps. The bobbit worm seemed to get the hospital that my partner works at very excited and I’m sure last week’s episode about plastic pollution will get many people thinking about the impact our daily lives have on the ocean.

For me personally, sitting watching the second episode of Blue Planet II and seeing those hydrothermal vents was a personal highlight. It will also go down as a big landmark in my research career. I spent about four months at sea in the Antarctic across three research expeditions, during my PhD at Newcastle University. I was part of team working on the hydrothermal vents where those crabs covered in bacteria live. The inspiration that lead me to sitting on a ship, watching a video feed from a remotely operated vehicle over two kilometers below, began with another David Attenborough documentary. This was not Blue Planet I but an even earlier BBC documentary series called Life in the Freezer, which planted the seed in my mind about becoming a marine biologist.

Becoming a Marine Biologist

Life in the Freezer aired in 1993. I was thirteen at the time. The opening scene where David Attenborough was standing in a vast snow and ice landscape was mesmerising. The series covered the ebb and flow of the ice around Antarctica and the animals that depend on the productive waters of the Southern Ocean. The part that really caught me was all the amazing life on the island of South Georgia. The coastal areas were packed full of elephant seals, fur seals, penguins, petrels and albatross. Little did I know that in just over ten years I would be living and working on the island.

I realised during that series that I wanted to be a scientist but not just any scientist, one that went to the Antarctic. I took Maths, English, History, Biology and Chemistry Highers and got onto a marine biology degree course. In my final year, I got my first opportunity to do some work related to South Georgia. I spent hours watching video footage of the deep-sea Patagonian toothfish and crabs attracted to baited deep-sea landers as part of my final year project. This was very fortunate because just as I was about to graduate a job working for British Antarctic Survey was advertised for a two-year fisheries scientist working on South Georgia on these animals. I applied. I got an interview. I didn’t get the job.

First disappointment, then an opportunity

The great thing about getting an interview is that you can often ask for feedback. So, I just asked the question “What skills and experience do I need to get the job?”. The answer sent me on a two-year mission in order to get what I needed second time round. This included: going back to university and doing a masters in Oceanography; learning to drive boats; sea survival training; and going to sea as a fisheries observer on a Portuguese deep-water trawler off Canada. My decision paid off because the job was advertised again. Once more I applied. Once more I got an interview.

Second time lucky

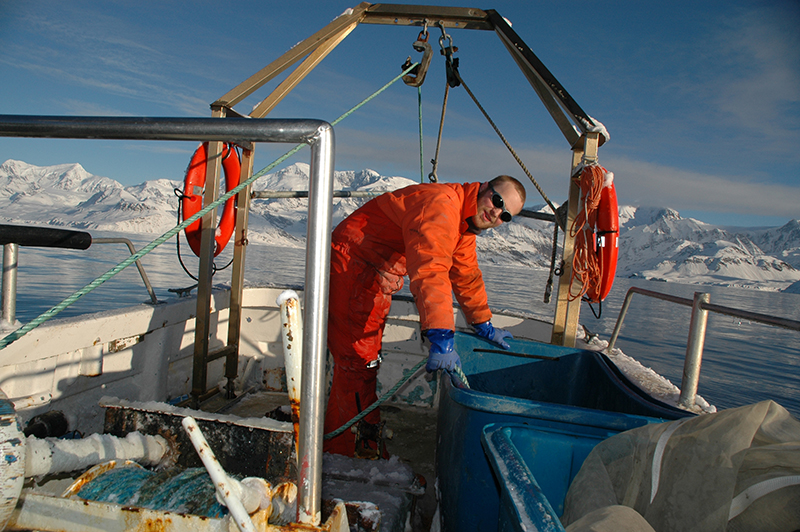

I got the job at British Antarctic Survey second time round. I was finally going to South Georgia! The next few weeks were a whirlwind of activity: medicals; advanced boat driving training; first aid courses; and learning to drive a JCB. Then I was finally deployed. I flew to down through South America to the Falkland Islands with part of the team that I would living and working with for the next two years. We sailed from the Falklands on the UK research vessel, the James Clark Ross, to South Georgia. I arrived in South Georgia on the 22nd November 2004.

The island of South Georgia was truly stunning. I spent two years on the island doing science that helped manage the commercial fisheries around the island. The research was varied. I worked on fish larvae, managed an aquarium which housed crabs, aged Patagonian toothfish using their ear bones called otoliths, undertook diet studies on icefish and went on fish stock assessments around the island.

The scenery and animal life were also truly amazing. I would go camping and hiking in order to visit Gentoo, king and rock hopper penguin colonies; climb snow-capped mountains; walk where explorers like Shackleton had been; and visit old abandoned whaling stations. The research base where I stayed was also in front of an elephant seal breeding beach for a couple of months of the year. I even met my current partner on the island. She was the doctor in my second year. But life on South Georgia had to come to an end.

Getting into hot water in Antarctica

Once I left South Georgia, I had a couple more months working for British Antarctic Survey back in Cambridge. I was wondering how on earth I would ever get back to the Antarctic. I stumbled across my next opportunity in the photocopy room. On the wall was an advert for a PhD at Newcastle University working on Antarctic hydrothermal vents. I applied. I got the PhD position. I moved to Newcastle.

The PhD was part of 5 year NERC programme trying to find and understand hydrothermal vents in the Antarctic. Hydrothermal vents are sites on the seafloor that release very hot fluids, rich in minerals into the water at the bottom of the ocean and are surrounded by high densities of life.

In 2010, I went back to the Antarctic as part of the first scientific expedition to sample these truly amazing habitats. We sailed on the UK science vessel, the James Cook with scientists from different universities around the UK. When we arrived at our first location, we used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to dive down over 2 kms to hunt for the vents. After a number of hours searching the seafloor we eventually found our first hydrothermal vent field. There was a huge amount of relief on the boat as the scientists got to work.

We visited a series of sites over the next 6 weeks along the East Scotia Ridge. We discovered whole new communities and species and mapped where the different animals lived around the vents. My work focused on what the animals were eating and constructing food webs at each of the sites we visited.

This brings me back to those hydrothermal vent crabs in The Deep episode of Blue Plant II. The crabs live in areas where hot water pores over them which provides the conditions for the bacteria to grow. We collected the samples from the vents using a suction sampler on the ROV Isis. I then looked at the biochemical composition of the crabs and the bacteria. They were very similar. This indicated that the bacteria living on those crabs were its food source.

These large-scale scientific expeditions are collaborative efforts. Scientist never undertake their work in isolation on these types of projects. They are a team effort, bringing together scientific disciplines. I worked with scientists that had backgrounds in chemistry, geology, microbiology, biology, computer science and supported by mechanical and electrical engineers, technicians and a large ships crew. There is no way I could have undertaken this work without the support of so many scientific and technical disciplines. They helped me add meaning to my work and place the results in the context of the system.

Will there be another Antarctic adventure?

Watching Blue Planet II the other weekend gave me a huge amount of personal pride. To sit there with my kids and my partner and show them on TV the Antarctic crab that I helped discover felt like a massive landmark in my scientific career. I was even there at the moment when the crab stuck its claw into the hot water. Life in the Freezer was the series that inspired me to work in the Antarctic, which set me on the road (or boat) to South Georgia for 2 years and then to studying for my PhD at Newcastle University.

For many people, Blue Planet II will inspire them too, some of whom will go into marine science as well. Whether you are into maths, biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, geology or microbiology, there is a career for you that involves our Blue Planet.

For me, I am about to start another Antarctic adventure. Next year, I am going to explore the seabed that has not been exposed to open waters for approximately 120,000 years. I’ll be spending about 3 weeks working in the area where a large chunk of the Larsen C ice-shelf broke off. The research team has been assembled from a number of different universities and institutions and will once more be a collaborative effort. It just goes to show that sometime adventures never truly end.

Find out more….

Marine research at Newcastle University

The Larsen C ice shelf mission