Professor Chris Seal is a Professor of Food and Human Nutrition, and Kay Mann is a postgraduate student, within the Human Nutrition Research Centre at Newcastle University. They are calling for the next government to introduce clear guidelines on the amount of whole grain we should be consuming.

The evidence: Whole grains are good for us

Current literature suggests that those eating three or more servings of whole grain, compared with those that eat none or only small amounts, have a 20-30% reduction in their risk of developing cardio-vascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Higher whole grain intake has also been linked to lower body weight, BMI and cholesterol levels. Other research suggests that eating whole grains can make you feel fuller for longer and that you do not need to eat as much of a wholegrain food compared with a refined version to feel full.

The problem: The picture in the UK

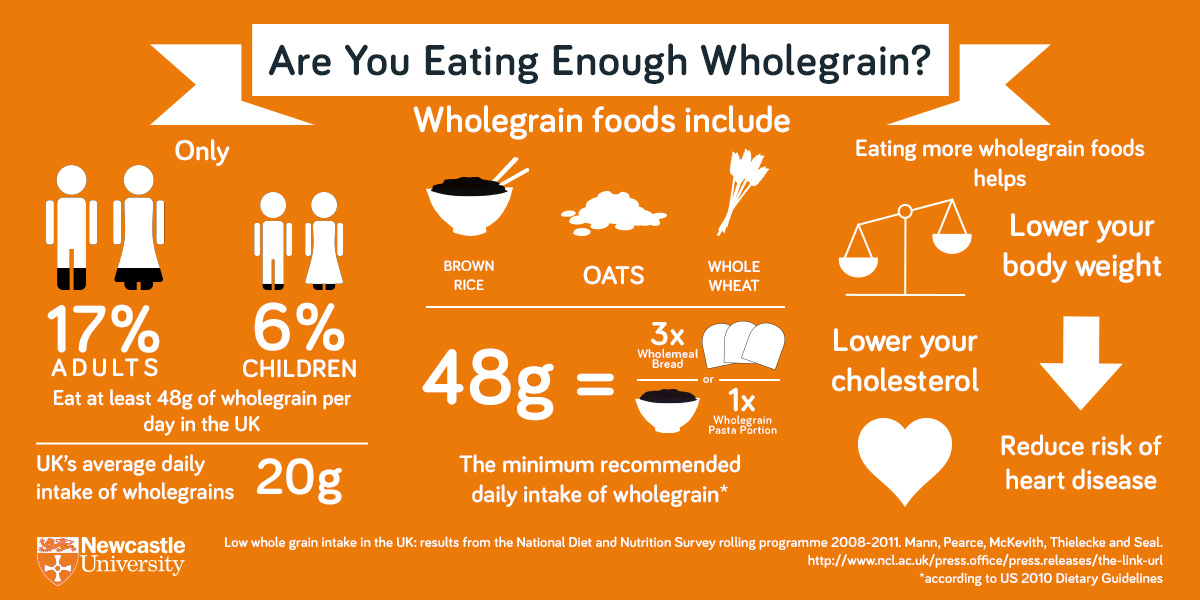

Our new research on over 3000 UK adults and children who took part in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) between 2008 and 2012 shows that over 80% of us are not eating enough whole grains. Amazingly, almost one in five people don’t eat any whole grains at all!

One reason for this may be that in the UK there aren’t any specific recommendations on the amount of whole grain we should eat each day, other than the NHS Eatwell Plate advice to “choose wholegrain varieties whenever you can”. Countries such as the US, Canada, Australia and Denmark give much more specific daily recommendations. These range from a minimum of 3 servings (or 48g) per day in the US to between 60g and 90g per day for women and men in Denmark.

Three servings (around 48g) is equivalent to:

- 3 slices of wholemeal bread

- A bowl of porridge or wholegrain breakfast cereal and a slice of wholemeal toast

- A portion of whole grain rice/pasta/quinoa or other whole grains

UK public advice about whole grains was first introduced back in 2007, when it was recommended to look out for ‘whole’ on food labels and to ‘choose brown varieties where possible’. We analysed whole grain intake from the NDNS back then and it seems little has changed in consumer habits since.

The amount of whole grain we eat in the UK is still very low – an average of around 20g a day for adults– compared with Denmark where the average daily intake is around 55g. In the UK, we tend to eat a lot of white bread, rice, pasta and cereals and lots of processed foods, all of which have no – or very little – whole grain in them and also tend to be higher in fat and sugar.

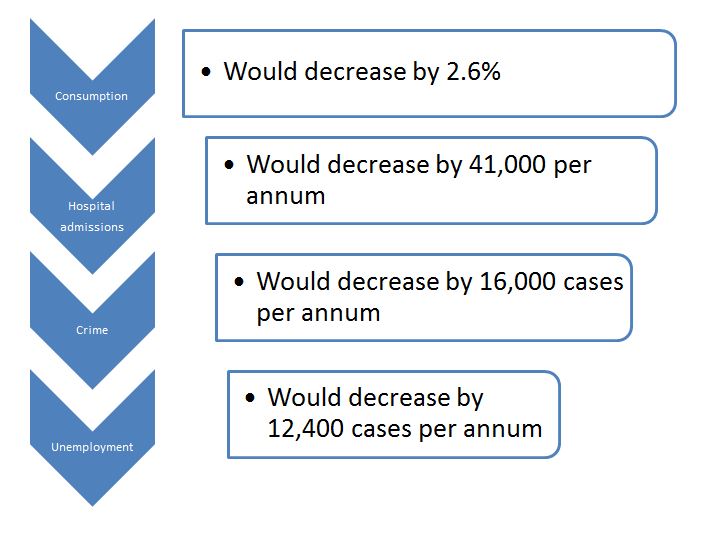

In Denmark, since the introduction of a whole grain campaign backed by the government and food producers, whole grain intake has risen by 72 per cent. We’d like to see a similar commitment here in the UK with a government-backed daily intake recommendation which can be used to develop successful public health campaigns.

So what are whole grains and what do they do?

Whole grains are defined as the ‘intact, ground, cracked or flaked kernel after the removal of the inedible parts such as the hull and husk’. This means that the three component parts of a grain – the outer bran, the germ and endosperm – remain in the final food product. Combined, these contain important nutrients such as fibre, vitamins and minerals and phytochemicals. When grains are refined to make white flour, many of these valuable nutrients are lost, and only a few are return with mandatory fortification.

Whole grains include; whole wheat (wholemeal), whole/rolled oats, brown rice, wholegrain rye, whole barley, whole corn/maize, whole millet and quinoa. The key is to look for the word ‘whole’ on an ingredients list and also for the ingredient to be high up on the list. These ingredients can be found in foods such as wholemeal bread, wholegrain breakfast cereals, porridge, wholegrain pasta and rice.

There are a small number of people that suffer from a gluten intolerance, which means that they have to avoid eating grains that contain high levels of gluten such as wheat, barley and rye. It is still possible for them to get their whole grains. Whole grain oats do not contain gluten but can sometimes be contaminated with wheat during harvesting and processing, others such as amaranth, buckwheat, brown rice and quinoa are also gluten free.

How whole grains have their effects is not clear. Certainly a key factor is better digestive health, but we also see lowered blood cholesterol, reduction in inflammation, lower body weight and lower weight gain in people who eat more whole grains.

The solution

We advocate:

- the introduction of specific guidelines to promote whole grain intake in the UK

- an emphasis on how easy it is to introduce more whole grains into diet – no major lifestyle change is needed

- small tweaks to diet such as replacing white rice and pasta for brown, eating porridge or a wholegrain cereal for breakfast instead of a refined grain breakfast cereal, or swapping white bread for whole meal bread