When visiting schools and museums our Street Scientists often get asked a variety of questions from curious children. Here are the answers to some of our favourite questions!

This week, we’re focusing on Biology questions around DNA and genetics.

First of all we should really explain what DNA is. It stands for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. It is essentially the building blocks of life. All living things, plants, animals and you are made of DNA. It is a big, long code that tells your body how to make you. You inherit your DNA partly from your mother and partly from your father – that’s why we often look similar to our families.

Do twins have the same DNA?

-asked by Lucy, 11, from Burnside Primary School

Well it really depends on what kind of twins you have. Monozygotic twins (the scientific name for identical twins) do have the exact same DNA as each other because both individuals developed from the same fertilized egg. Dizygotic twins, (non-identical twins), don’t have the same DNA since the individuals are formed from two different eggs that are fertilised at the same time, this is also how twins can be born one boy and one girl.

– JC, Medical Student

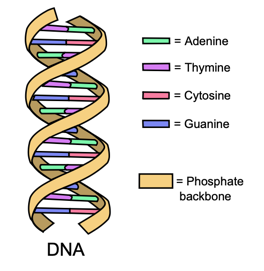

How is DNA created?

-asked by Nicole, 11, from Burnside Primary School

DNA is created as a double helix (imagine a twisted ladder shape) of two complementary strands, which mean the strands are matched up to each other. These DNA strands are made of chemical building blocks called nucleotides. We can think of this building blocks as ladders. Each building blocks are made of three parts: a phosphate group, a sugar group and one of four types of nitrogen bases. To form a strand of DNA, nucleotides are linked into chains (one side of the ladder formed), with the phosphate and sugar groups alternating. They are formed like a spiral ladder, where the phosphate and the sugar molecules are the sides and the nitrogen bases act as the rungs. The base from one strand is then connected to complementary base of another DNA strand. So, even though the molecules are very long, a DNA is compact and coiled, which enables it to fit inside packaging we call chromosomes. In humans, we have 23 pairs of chromosomes inside the nucleus of our cells. These contains information and instructions needed for us to develop, grow and reproduce.

– Aurelia, Dental student

How many genes are in a body?

-asked by Kian, 9, from Hylton Castle Primary School

Every cell in your body has a nucleus with the DNA containing all of your genes. Each gene has the special code to make one of the proteins used to build the body. If you stretched out all the genes in the DNA of one cell it would be 2 metres long, and each person has 37 trillion cells! The DNA is very tightly coiled into 23 pairs of chromosomes, one of each pair comes from your mum and the other from your dad. This is why you and your siblings have some features from each of your parents. Scientists say we all have 25,000 genes that decide everything from your skin colour to your height. Everyone has different genes, apart from identical twins, meaning we are all unique and there is no one exactly like you in the entire world!

– Ailie, Evolution and Human Behaviour Masters Student

Is it possible to make a dinosaur come back to life using similar DNA?

-asked by Noah, 11, from Burnside Primary School

A great question, I definitely hope so, but we would have to be careful we don’t want a Jurassic park situation! Some people might say the most similar thing to a dinosaur nowadays would be a reptile, but dinosaurs were more likely warm blooded, unlike reptiles. The most related live group of animals to dinosaurs are birds, did you know chickens are thought to be distantly descended from a T-rex? However, birds aren’t very dinosaur like. Say we wanted to bring a diplodocus back to life, our best bet would be to try and find some source of DNA for example blood in the body of mosquito trapped in amber (like in jurassic park!) and splice (which is like fusing or attaching) it to a similar animal’s DNA.

Scientists have been working on a way to bring Mammoths back, using DNA from dead mammoths which were frozen in ice! They are splicing this DNA to elephant DNA to try and create a hybrid mammoth/elephant hybrid. It might be easier to bring a smaller dinosaur back, like a Compsognathus (a turkey sized dinosaur which was thought to eat small lizards and insects) by forming a hybrid with the most closely related animal today. Whilst scientist haven’t made mammoths de-extinct yet, they have managed to do it briefly with Pyrenean Ibex (a sort of mountain goat with big horns although sadly this didn’t live very long) so perhaps in the future there is hope yet for dinosaurs and mammoths to return, I certainly hope so!

– James, Biology and Psychology Student