In August, ICaMB‘s Tom Williams (a postdoc in Martin Embley’s lab) was invited to attend Sci Foo camp. Here he tells us all about it.

By Tom Williams

This is a post that’s been brewing for a while, since I returned from Google’s headquarters for the Sci Foo 2014 unconference last August. It’s taken the New Year cobweb cleansing (and an inopportune corridor collision with Neil) to get me to sit down and write it, but that’s also given me an opportunity to process and reflect on the sensory overload resulting from two-and-a-bit days of discussion, debate and near-constant mental stimulation I experienced last August in Mountain View.

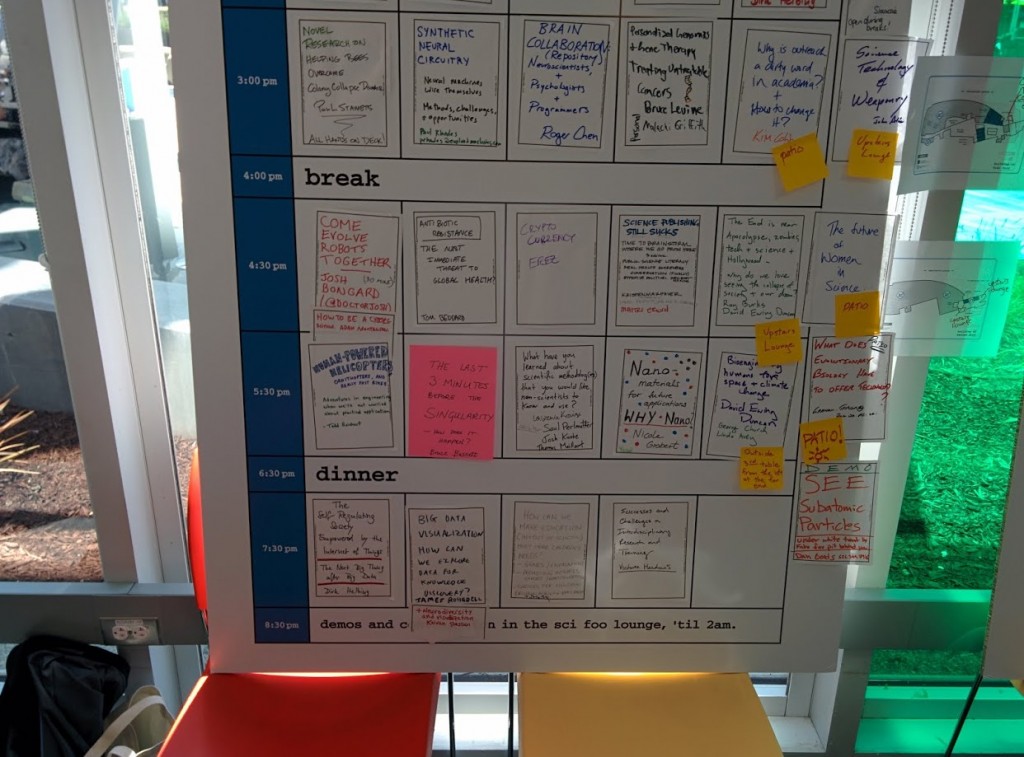

First off, what’s an unconference, and what’s Sci Foo? Although they’re becoming more common in computing and technology-related fields, unconferences are still pretty rare in biology. They’re participant-driven conferences in which the attendees determine the programme on the fly — in our case, by hastily scribbling session ideas on pieces of paper stuck to a whiteboard!

Sci Foo, which is organised by Digital Science, O’ Reilly Media (Foo stands for Friends of O’Reilly) and Google, is an annual, invitation-only science-themed unconference with participants from across the traditional scientific disciplines as well as science publishers and technologists. I’d heard about the event, but didn’t know much about it — and my first thought when the invitation email arrived was that the whole thing was a scam! Luckily for me it turned out to be genuine, and, with some financial support from ICaMB to cover my travel costs, I was bound for California at the beginning of August.

One of the things I’d noticed in the invitation was that Sci Foo was surprisingly short by usual conference standards – a day and a half of scheduled sessions, with an ice-breaker the night before. On arrival, the reason soon became clear – this was easily going to be the most intense, and intensely stimulating, meeting of my career. The range of backgrounds and perspectives among attendees proved to be hugely exciting, if more than a little daunting, and at the opening barbecue I found myself rapidly paring back my usual conference intro into something that musicians and videogame designers – let alone physicists – might find at least somewhat meaningful (Incidentally, this experience turned out to be very helpful for explaining my work to non-scientist friends and relations, and this Christmas may have been the first time I was properly able to explain to my in-laws what it is I actually do). I was struck not only by the breadth, but also the quality (and in many cases, the fame) of the other attendees, and began to wonder – not for the only time that weekend – why exactly I had been invited! This seemed to be a common feeling for many of the participants, and turned into a fairly reliable opening gambit with other less eminent members of the gathering over the following days.

It’s difficult to succinctly describe the mental atmosphere that developed at Sci Foo over the following two days. I’ve already referred to the intensity, but the freeform nature of the whole event, and the enormous diversity of the topics on offer were also key elements in the heady mix. I wasn’t necessarily learning all that much about my own field, nor was I really making contacts with potential scientific collaborators – the usual hallmarks of a successful conference – but I was being exposed to areas of inquiry which were entirely new to me, often by leaders in their respective fields, and the overall feeling was that of being a kid in an intellectual sweet shop.

Although I began by attending sessions on biology and evolution, I soon found that the most interesting experiences were to be found in sessions far outside my field of expertise. One early session that sticks out for me was a broad round-table discussion on new tools revolutionising different scientific fields. I spoke about how new sequencing technologies are allowing us to explore the world of uncultivated microbial diversity for the first time, and the impact this new data is having on our understanding of the tree of life. This was followed by Lawrence Krauss and Saul Perlmutter discussing techniques for detecting gravitational waves closer to the big bang than ever before, and the implications these findings might have for theories on the origin of the universe! This was one of several moments during the weekend when the links between research into biological and cosmological origins became very clear, and I began to lament my ignorance of physics – something I’m now working to at least partially correct through popular science.

Not all the sessions were quite so profound, even if they were interesting in many other ways. In one session, we put the results of the hilariously-titled 1997 paper “The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness” (Aran et al. 1997) to the test. Participants were paired up with strangers and given 45 minutes to discuss a series of questions designed to promote feelings of warmth and familiarity. The procedure worked oddly well, and a general feeling of scepticism in the room soon gave way to laughing, joking and free-flowing conversation – a palpable drinks-reception atmosphere without the booze. Neither I nor my randomly-assigned partner – a Scandinavian biochemist – were immune to the effects, and a genuinely weird feeling of intimacy had developed by the end of the session. The questions seemed to work by leading participants from standard small-talk, through topics of gradually increasing intimacy, to questions about deeply-held values and philosophical perspectives, condensing the normal development of a friendship (or courtship) into a single sitting. The experience raised interesting questions about how easily our emotions and perception can be manipulated, and the session ended with a stimulating discussion; it wouldn’t surprise me if some of those nascent relationships were continued more discreetly elsewhere!

Some of the sessions were more closely related to my own research interests. I’m a keen advocate of open data, and I typically upload the datasets associated with my papers to repositories such as Dryad and figshare. So it was really interesting to meet up with Chris George and other members of the figshare team to share experiences and discuss the future of scientific communication. Everyone agreed this was going to involve more transparency in terms of publishing raw data and negative results, and we discussed the necessity of new algorithms for filtering and making sense of the resulting data deluge. Most of the participants were computer scientists or, like me, computationally-inclined biologists, though, for whom data availability and re-use – especially of other people’s data – is almost always a good thing, and I wonder if more traditional wet-lab biologists would have been quite so unanimous in their agreement.

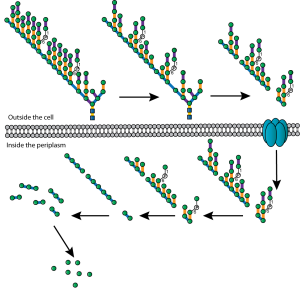

There was also much to enjoy at Sci Foo that was just plain awesome. Andy Carol‘s functional LEGO recreations of famous computing machines – from Babbage’s Difference Engine to the Antikythera Mechanism of Ancient Greece – ranked very highly among these, as did the beautiful “nanoflights” (stop-motion films based on scanning electron microscopy) of Stefan Diller

The proboscis of the glasswinged butterfly, Greta oto; a nanoflight still by S. Diller, http://www.nanoflight.info/.

Drosophila, S. Diller, www.electronmicropscopy.info 2015

This mix of art, fun, discussion and synthesis across so many different disciplines felt really unique and perhaps best captured the feel of Sci Foo for me. Unconferences like Sci Foo are very different from the usual academic conference, and while I found that freshness to be enormously stimulating, the lack of formal structure also posed a number of challenges. I think it partially depends on how extroverted you are: I’ve grown used to the semi-formal setting of a talk or poster session, where the roles of presenter and audience member, and the times for discussion, are much more clearly defined. Unconferences demand and reward participation: you may have to drag yourself out of your own shell, but the outcomes are ultimately very worthwhile; at the same time, Sci Foo is clearly an environment in which “alpha academics” will thrive from the off! Overall, I had a fantastic time at SciFoo and the unconference experience is one that I’d unreservedly recommend to any scientist. A quick Google search will turn up a number of upcoming unconferences in the UK, most of which are open to anyone, although they tend to be on tech-related topics. Still, it might be an interesting structure to consider when organising future away days or postgrad conferences…