Anyone who has studied biology has seen an image of the tree of life in the text books. Most of us think of this as being set in stone, one of the rock solid foundations on which evolutionary biology is built. However, all is not quite as settled as it seems. Recently, a Nature article from the laboratory of ICaMB’s Professor Martin Embley challenges the traditional three domain structure of the root of life. Here, first author on the paper, Dr Tom Williams, tells us the story.

By Dr Tom Williams

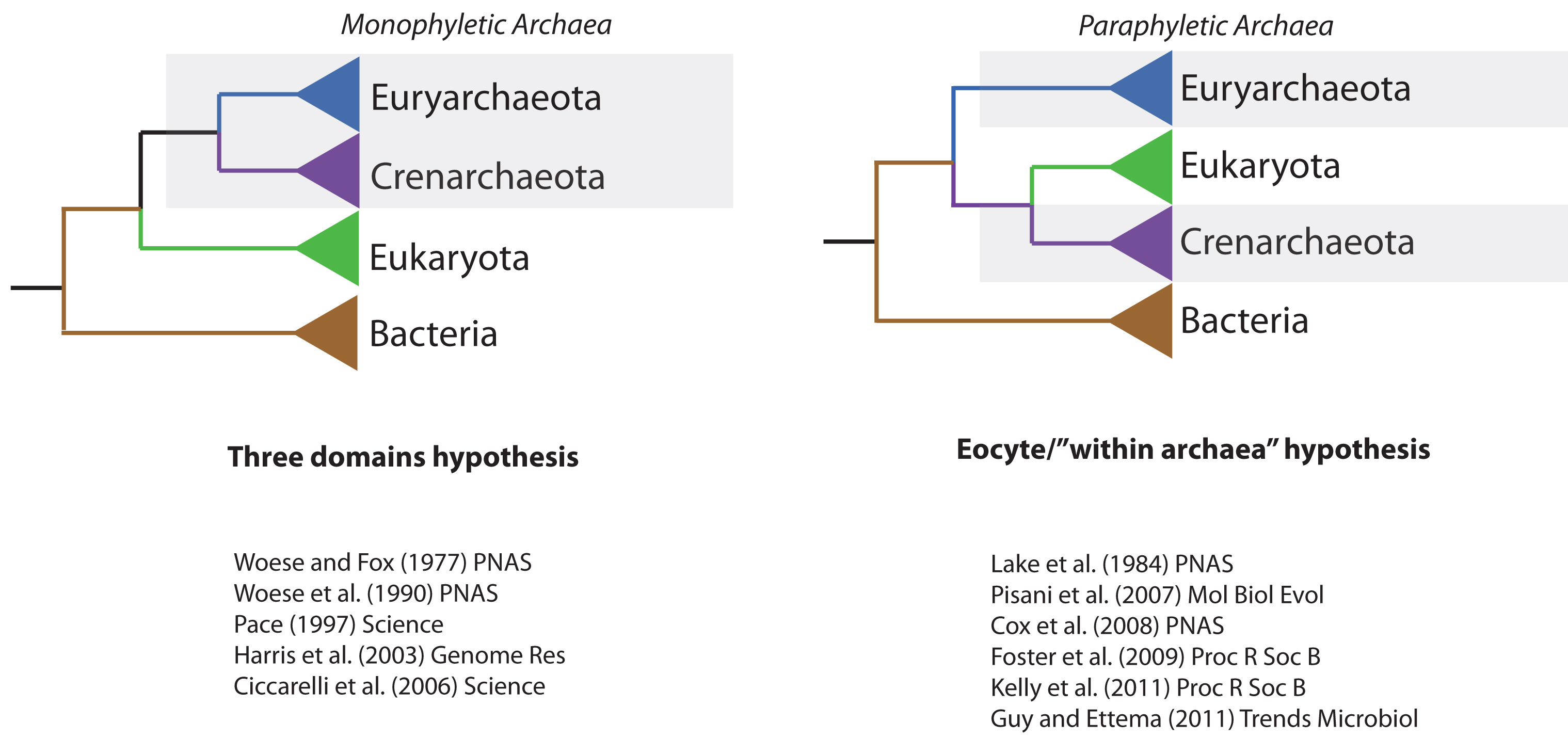

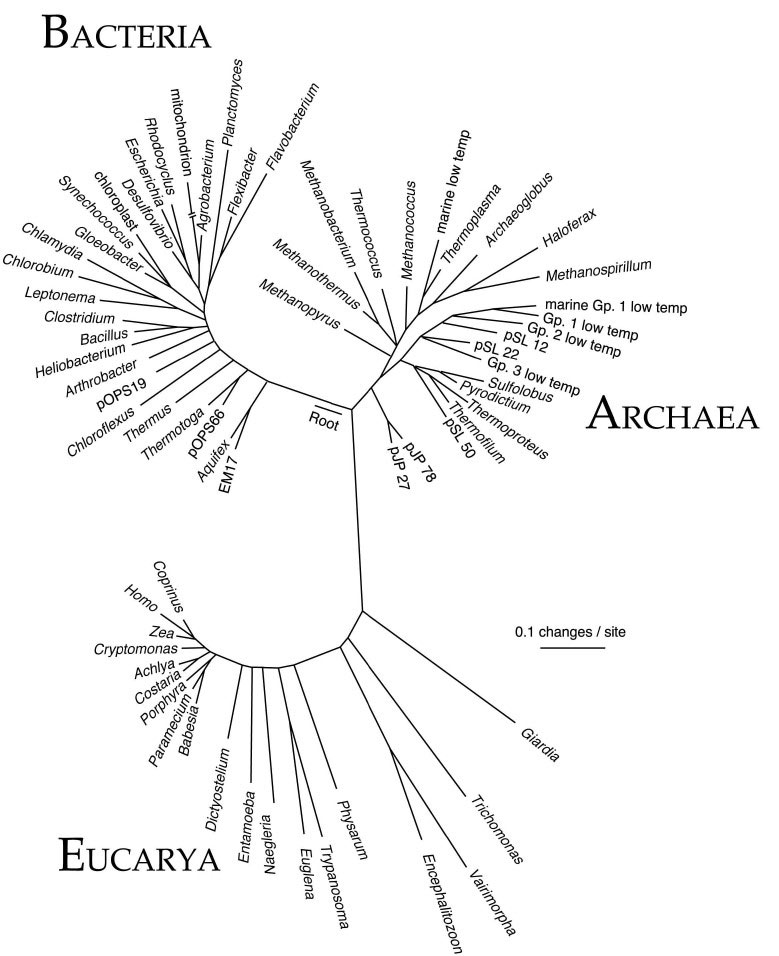

Our modern understanding of the tree of life began in 1977 when Carl Woese and his colleagues discovered the Archaea, a group of prokaryotes originally isolated from extremely hot or salty environments. Although Archaea looked indistinguishable from Bacteria under the microscope, their gene sequences were at least as different to those of Bacteria as from the eukaryotes – the group of organisms, including fungi, animals and plants, whose cells contain a mitochondrion and a nucleus. According to these analyses, living cells should be classified into three main groups: Bacteria, Archaea and eukaryotes – rather than the two (prokaryotes and eukaryotes) that had previously been established based on cell structure. In 1990, Woese and his colleagues published another seminal paper in which they argued for this “three domains” classification. This three-domains tree has become an iconic image in biology, and is often found in the popular science literature, as well as many textbooks – you’ve probably seen it before. Here it is from a 1997 review by Norman Pace:

The traditional 3 domain Tree of Life. From: A molecular view of diversity and the biosphere. Pace NR Science (1997) 276: 734-740

This was certainly the tree of life that I was familiar with, first as an undergrad and later as a Ph.D. student at Trinity College Dublin. So I was surprised and very intrigued when a certain Martin Embley came to talk at an Irish bioinformatics meeting, claiming that support for the three-domains tree was not as strong as you might expect. New work from his lab instead favoured the “eocyte tree”, in which the eukaryotes (or, at least, some of their genes) actually evolved from within the Archaea. If true, this tree would imply that there were originally only two types of cells – Bacteria and Archaea – and that the eukaryotes (i.e., us!) originated later in a partnership between the two primary domains.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and I was thinking about where I wanted to do my postdoc. I remembered Martin not only from that talk, but also from some interesting work (2nd link) he had done on a group of parasitic fungi called Microsporidia. I joined his group and began working on microsporidians, but I was still very interested in the tree of life and the origin of eukaryotes. In the meantime, DNA sequencing technology had been improving, and microbial ecologists were beginning to publish genomes from new groups of Archaea that could not be grown in the lab, and so had never been studied before. One of the really exciting findings from these studies was that some Archaea contained genes that looked very similar to fundamental components of our own cells, such as actin and tubulin – two proteins that help to define the microscopic “skeleton” of eukaryotic cells. When we added these new genomes to our analyses, we found even stronger support for the eocyte tree; those findings were reported last year in Proceedings B. At about the same time, a number of other researchers were reporting something similar: as our view of archaeal biodiversity increased, support for the three-domains tree was on the wane. Given the prominent position of the three-domains tree in the literature, and the importance of this question for understanding early life on Earth, we decided to write a review summarizing these recent developments in the field – it came out in Nature this week, and it’s the reason for this blog post!

As we delved back into the 30 years of literature on the molecular tree of life, one of the most interesting discoveries for me was a seam of eocyte literature that I hadn’t been aware of previously. Although many analyses over the past three decades have recovered the three-domains tree, and it appears in all the textbooks, the literature has actually never been unanimous in its support. Nonetheless, it is only in the last five years or so that support for the eocyte hypothesis has reached critical mass, perhaps due to improvements in our statistical methods and, more recently, sampling of archaeal biodiversity.

The Embley lab: Back row, left-to-right: Kacper Sendra, Martin Embley, Tom Williams, Robert Hirt. Front row: Shaojun Long, Ekaterina Kozhevnikova, Andrew Watson, Paul Dean, Maxine Geggie,Alina Goldberg-Cavalleri, Sirintra Nakjang.

Of course, our latest work is almost certainly not going to be the last word on the relationship between eukaryotes and other cells. Our methods are getting better – in part thanks to the statisticians we are collaborating with here in Newcastle – but there is much room for improvement, and so much about the microbial world that we still have to discover. Still, if the eocyte tree is correct – and it appears to be the best-supported tree on the current evidence – then that has important implications for how we understand early life on Earth and the origin of our own cells. For one thing, it rules out the eukaryotes as a primordial cellular lineage, as old as the Bacteria and Archaea. Instead, it suggests that the Bacteria and Archaea were established and diversifying on Earth before the origin of eukaryotes, resurrecting the concept of an “Age of Prokaryotes” on the early Earth. Of course, when you think about the phenomenal number of Bacteria and Archaea that live in your own body, never mind the wider environment, you might well argue that it never ended…

This work was supported by a Marie Curie postdoctoral fellowship to Tom Williams. Martin Embley acknowledges support from the European Research Council Advanced Investigator Programme and the Wellcome Trust.

Links

The Nature Article: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v504/n7479/full/nature12779.html?WT.ec_id=NATURE-20131212

The Proceedings B paper: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/279/1749/4870

The Embley lab website: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/microbial_eukaryotes/

Microsporidia papers: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v452/n7187/full/nature06606.html

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v453/n7194/full/nature06903.html