by Prof Bob Lightowlers

It was 2pm on a Tuesday afternoon and there I was watching television in my office. An unusual experience (honestly) but it was to be a truly momentous occasion. For the next 90 minutes, members of parliament would be debating whether to sanction the procedure of mitochondrial donation. What on earth does that mean ? Well, mitochondria are essential compartments (or organelles) that provide numerous key functions for the cell. They also have their own genome, called mitochondrial DNA – mtDNA – that contains the information to make up just 13 proteins, all of which are important in their function of producing main energy source of the cell, ATP. This is why mitochondria are often referred to as the cell’s batteries or the powerhouse of the cell. It is important to note that mtDNA is very small when compared to the nuclear DNA component: 16 thousand mitochondrial nucleotides (that is, the “letters” in the genetic code) vs more than 3 billion nucleotides in the nuclear DNA.

OK, but why would you want to donate mitochondria?

Mitochondrial DNA is strictly passed down via our mothers, unlike nuclear DNA which is comes from our father and mother. Almost 2,500 women in the UK have mutations in some or all of their mtDNA that can cause disease. Defects of this mitochondrial genome, can be responsible for a wide spectrum of mainly muscle and neurodegenerative disorders for which there is no treatment. By identifying those women with defective mtDNA, we could potentially prevent transmission of their unhealthy DNA by substituting their mitochondria for organelles from a donor. Simple on paper!

What’s the problem?

There are two major barriers. First, how safe would any technique be for mitochondrial donation ?

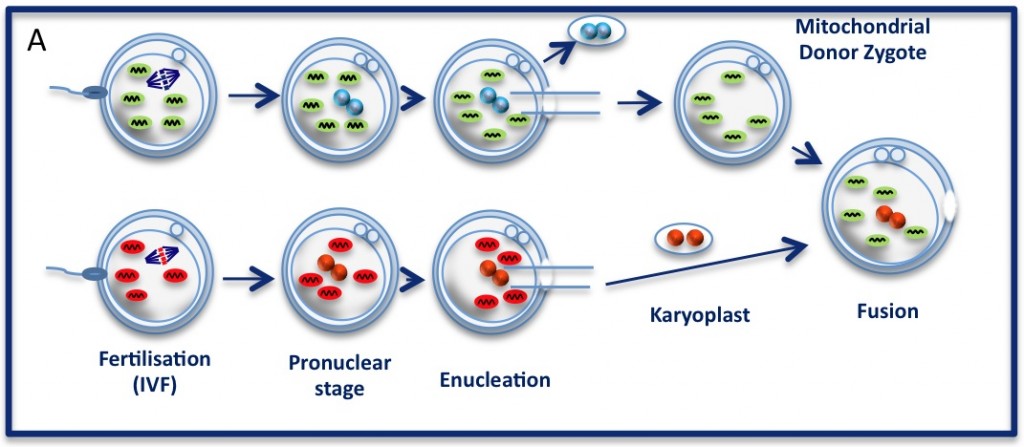

The pronuclear transfer method: Embryos are shown with mitochondria carrying normal (green) or mutant (red) mtDNA.

As the embryos begin to develop, pronuclei become visible. Pronuclei from the normal donor embryo are removed (blue, top panel ‘enucleation’) and are replaced with the nuclear DNA from the patients (red, karyoplast). The resultant embryo carries nuclear DNA from the patients and mtDNA from the donor (mitochondrial donor zygote).

The technique being championed in Newcastle is that of pronuclear transfer. The idea is to take the nuclear DNA from a fertilised embryo and transfer the DNA to a donor with no nuclear DNA, ie, where the nucleus was removed. The newly made embryo then has nuclear DNA from the mother and father but has only mtDNA from the donor.

As you can tell, there is quite a lot of tricky manipulation here. Further, although the mtDNA that has been replaced carries only a very small number of genes, could these somehow be incompatible with the nuclear DNA?

After many years of very careful analysis, there is no evidence to suggest that this procedure is unsafe. The question of incompatibility would also seem to be highly unlikely. After all, nature has been performing the experiment of mixing and matching nuclear and mtDNA since the evolution of Homo sapiens. The idea that, for example, there would be something wrong with the child of an aboriginal woman and a inuit man due to the substantial differences in their mitochondrial DNA would seem laughable.

In addition, does the replacement of DNA, albeit the complete mitochondrial genome, constitute genetic manipulation? This is a contentious issue and a strict definition of what constitutes genetic manipulation, particularly when concerning mtDNA, is difficult to agree on. It must be remembered that mtDNA is completely separate from nuclear DNA and needs to be considered as such.

A separate issue is that many people are ethically uncomfortable with this process. Can embryo manipulation ever be acceptable? Certainly, many religious people have a deeply felt objection to this.

Even when we accept that these methods could offer such an immeasurable benefit for many couples, it is clear that there were many questions to be tackled before we could consider the prospect of mitochondrial donation. For this reason, experimentation and public consultations had to be initiated.

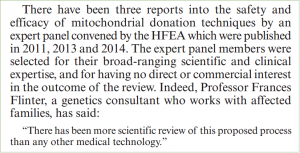

The Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Health, Jane Ellison, when presenting the vote on Tuesday highlighted the measures taken to date to assess the safety and ethical concerns surrounding mitochondrial donation.

To cut a very long story short, both have been carried out for many years, including supportive public consultations and independent review by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) reporting that the procedure was not dangerous, as we’ve covered before (here and here). Following these procedures, Professors Turnbull, Herbert and numerous members of the Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research were instrumental in persuading the government to finally hold a debate in the House of Commons.

The vote scheduled for Tuesday afternoon would decide whether the HFEA would have the right to offer a licence to perform mitochondrial donation, a first for the UK and the world. The week leading up to the debate was a white-knuckle ride. Letters of support were published in leading newspapers from Nobel Laureates and other eminent scientists. Just when it appeared that the tide was turning, the Church of England announced it could not support mitochondrial donation. This was a great disappointment and rather a shock, as they had been involved throughout the lengthy consultation processes and had not indicated their level of concern.

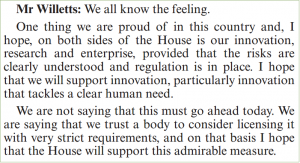

Now a back-bench MP, former Minister for Science, David Willetts, made a clear case in support of mitochondrial donation. You can read the whole debate here.

Back to me watching the television. At 3:45pm, the members had cast their votes and the count was in – 382 for the motion, 128 against! This is a fantastic result. It gives couples who may be at risk of having a baby with mitochondrial disease the chance to choose whether they want to try mitochondrial donation, just like couples have been able to choose in vitro fertilisation since the 1970’s.

Obviously, this result has gathered lots of media interest and even I was rolled out to perform a couple of interviews.

There is still more to be done, however. Further important research to support the safety of the procedure is currently in review but it must be recognised that every clinical procedure carries a risk. What this vote does is to empower the HFEA to licence this procedure in the UK, but this is still an important barrier and many issues are still to be addressed. And it also needs to be discussed by the House of Lords, of course.

Regardless, today’s vote was a wonderful day for anyone who has been touched by mitochondrial disease in any form. Twenty years ago, Doug Turnbull and I used to discuss this idea. He and his colleagues have done a remarkable job to make this pipedream a reality.