We all know the history of Bonfire Night, but do you know the science?

The Explosion

All fireworks are essentially a combustion reaction, like fire, that produces light and heat.

Fireworks tend to have a long fuse that burns slowly so you have time to light the fuse and run away before the big bang! The fuse first reaches a compartment containing gunpowder, it ignites this causing the firework to launch into the night. There is a delayed fuse to ignite the next explosion, this heats the “stars”.

The stars in a firework are individual compartments containing a different composition of chemicals, depending on the desired colour and effect of the firework. The stars may even be arranged inside the shell of the firework so that they burst in a certain formation to form a shape.

The Colours

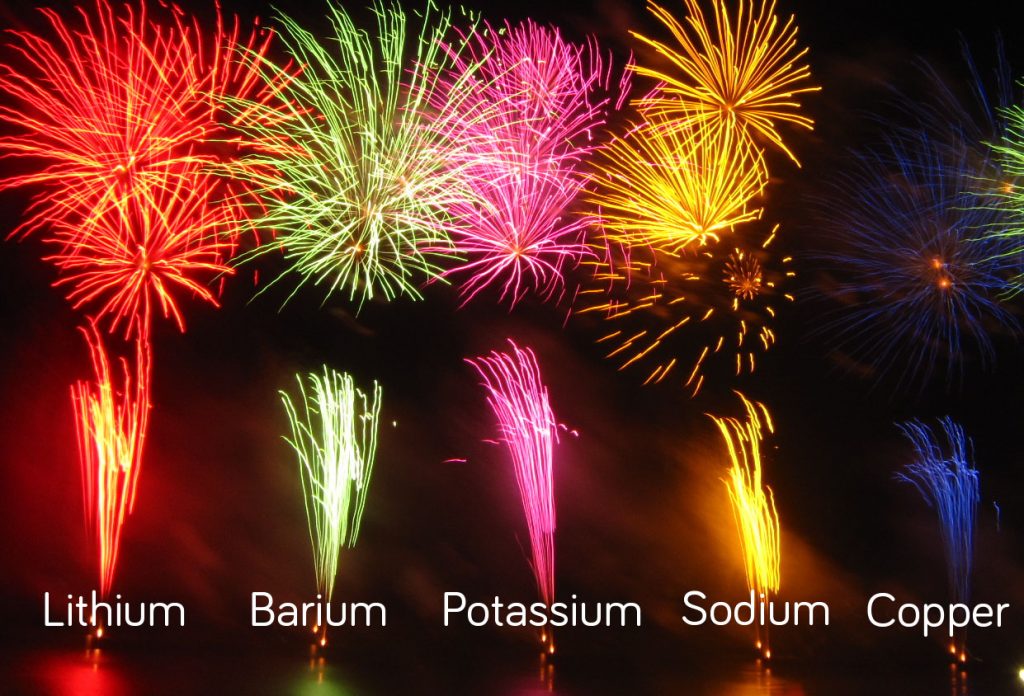

Firework displays always use a range of striking colours, the variety of colours comes from the use of different chemicals. Elements such as barium, copper and lithium burn with a coloured flame and are chosen for use in fireworks due to the bright colours they produce.

The Sound

When the chemicals inside the firework’s shell are heated they convert from a solid to a gas. The gas takes up more space than there is available inside the shell so it bursts out creating a loud BANG.

Crackling noises come from fireworks which contain lead. When lead oxide is heated and vapourised, the vapour atoms produce crackling noises.

The whistling sound that you hear when the fireworks shoot up in the air, comes from the firework tube itself, not the chemicals. When the tube is partly empty, it will vibrate the air passing through it, causing a whistle.

How can you write your name with a sparkler?

I’m sure you’ve all held a lit sparkler at some point and twirled it around in the air to see a trail of light lingering in the air for a few seconds. The truth is the light isn’t really still there but your eyes play a trick on your brain to make you think that it is. Our eyes don’t react as quickly as you might think when our view changes, they usually keep the old view around for a fraction of a second. This is known as visual persistence and it’s what allows us to view a series of still images as movement. The effect is increased in the case of the sparklers due to the very bright light emitted form the sparks contrasting against the dark background. This makes the light appear to last longer.