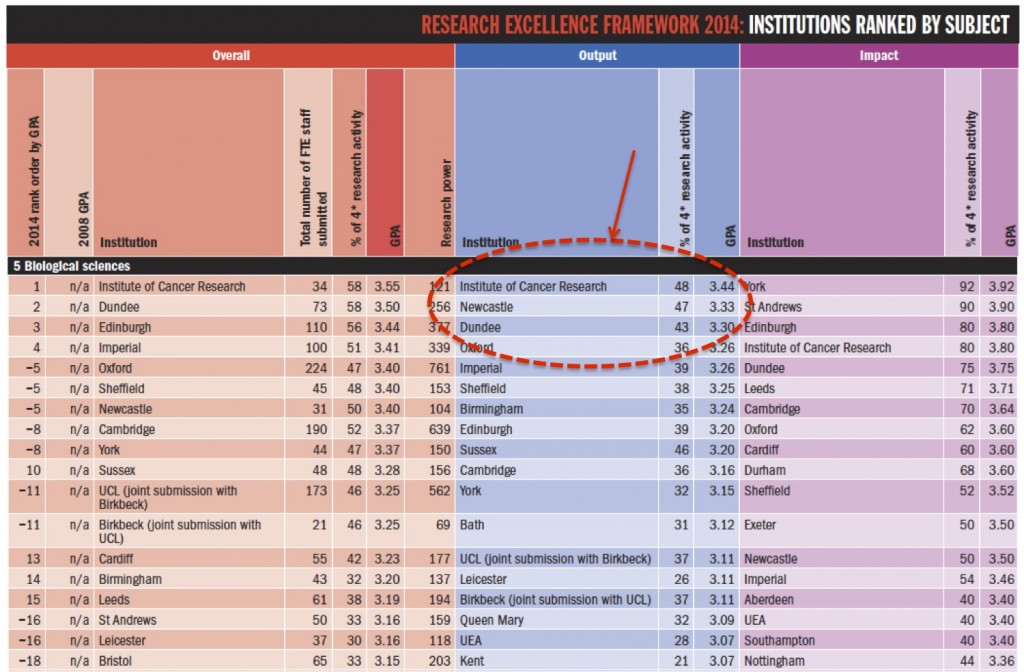

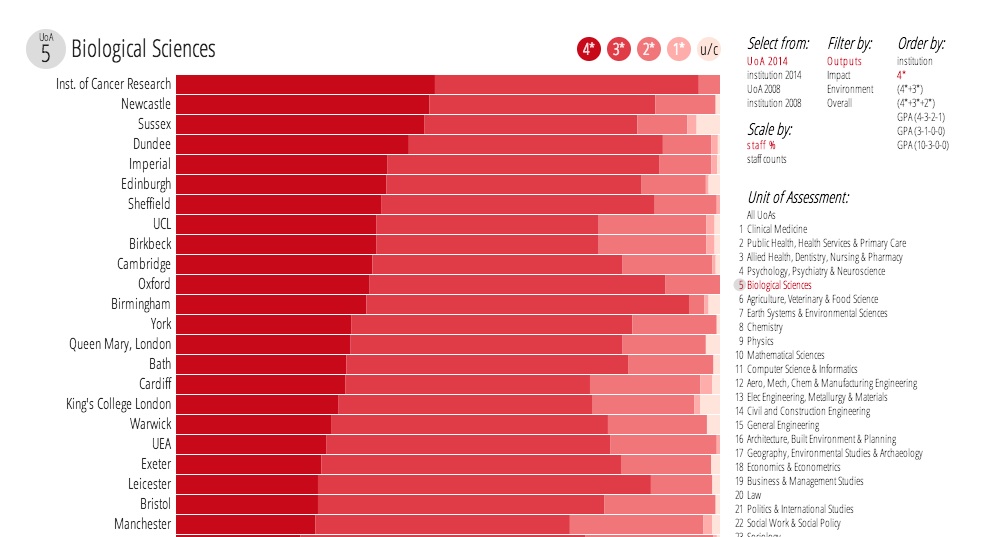

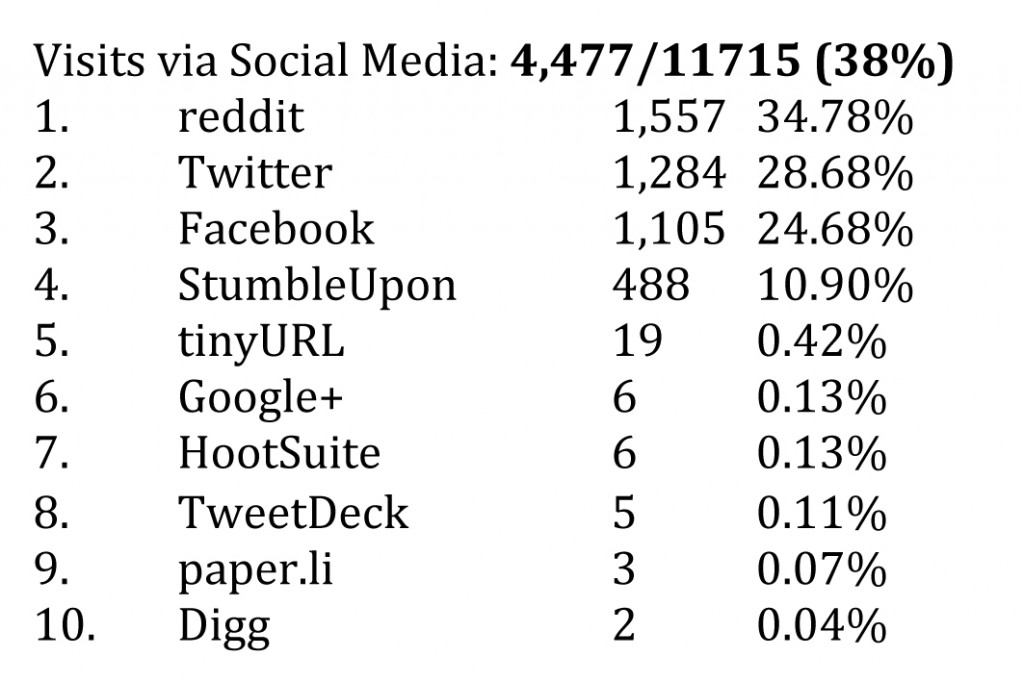

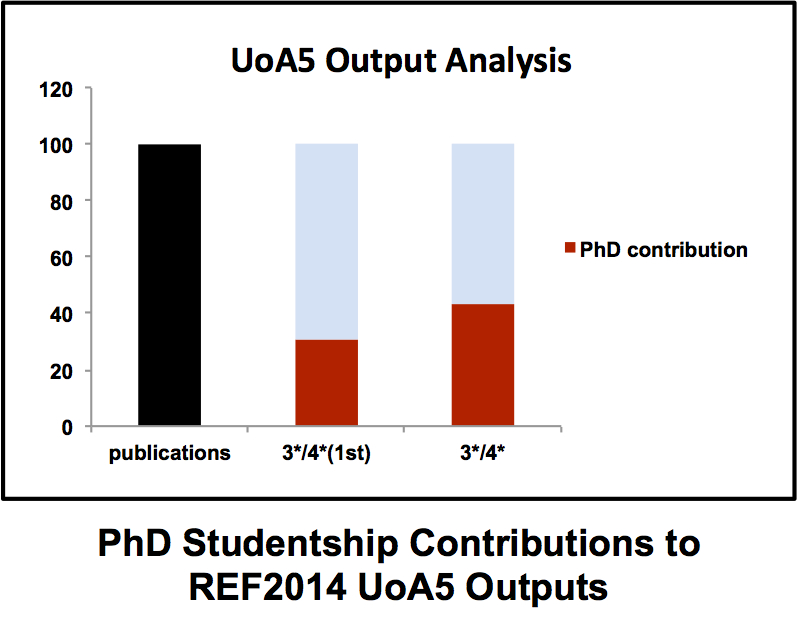

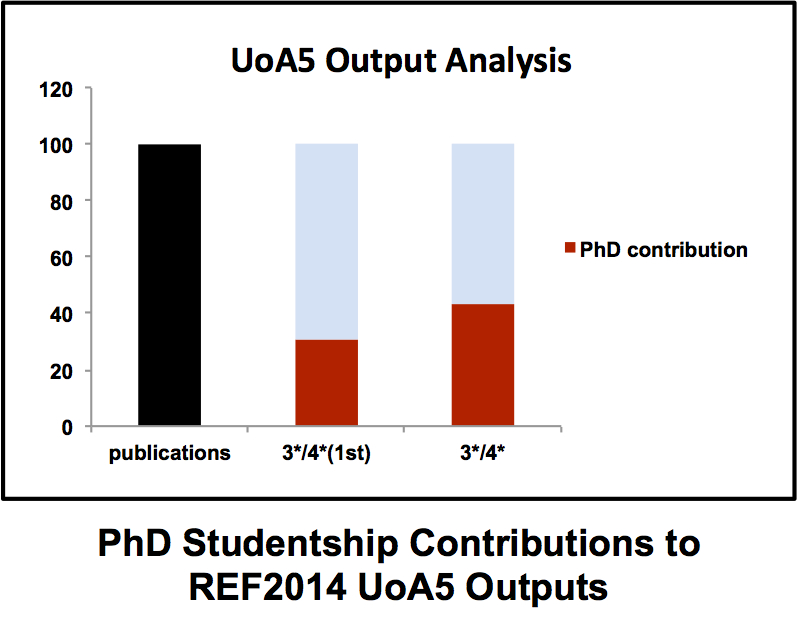

A strong and vibrant PhD programme is essential for any successful academic department. PhD students bring energy and enthusiasm to their projects (well that’s the idea anyway) that frequently reminds many jaded professors contemplating the hell that is ResearchFish why they went into this business in the first place. Typically a PhD student progresses from hesitant first steps in the laboratory to becoming a confident scientist with ownership of their project. Although in the moments before a PhD viva some of that confidence has been known to slip away. The ICaMB Postgraduate Research Symposium is an important showcase that allows our final year PhD students to demonstrate not just the exciting science they have been doing but also just how far they have come over the last 3/4 years. But there is also a serious side to this for ICaMB. In the last REF (where we <cough> did quite well), our PhD students made a major contribution to our returned papers. Brian Morgan has crunched the numbers and discovered that PhD students were first authors on 30% of our 3*/4* submissions (see Figure), including papers in Cell (x2), Nature, Science, Molecular Cell, Nature Chemical Biology (x2) and PNAS (x3). Moreover, in our UO5 return, 3 out of 4 of our Impact cases were underpinned by PhD student research.

This year, the first day of the symposium was on March 14th with a second to be held on April 29th. We’ve covered the ICaMB PhD symposium before but this year we thought we’d do something different and ask some of the PhD supervisors what this meant to them. All of us are proud of the PhD students that come through our labs, even if, occasionally, there are some grey hair inducing moments on the way. Seeing a final year student confidently discuss their project and answer questions is an important moment for a PhD supervisor. Below we have a varied group of supervisors, from a definitely not jaded professor discussing their final PhD students, to a newer PI discussing their first.

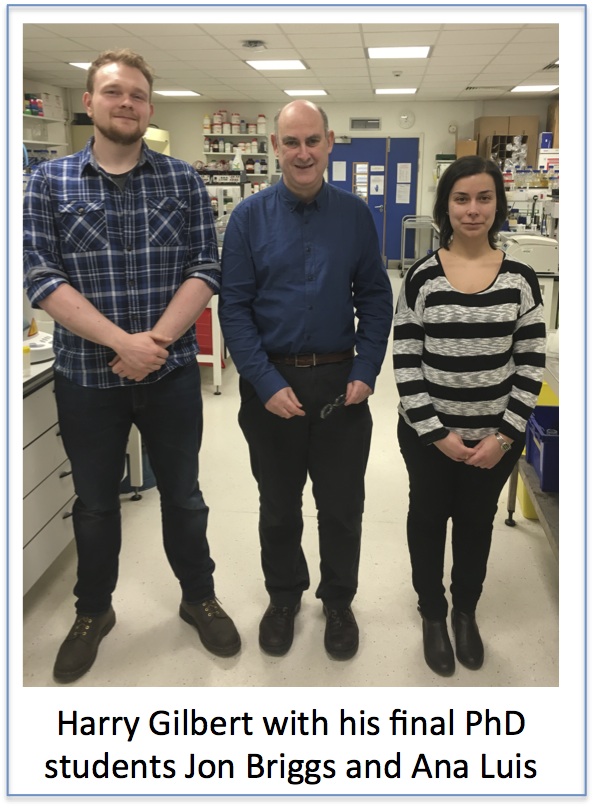

Harry Gilbert: Ana Luis and Jon Briggs

The two final year students from my laboratory who are contributing to the 2016 Postgraduate Research Symposium are Ana Luis and Jon Briggs. These are my last PhD students and it is great to finish with such excellent scientists. Neither student is on the traditional BBSRC/MRC DTP. Jon is supported by the Faculty to work on my Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award and Ana is funded mainly from my overheads and more recently by my ERC grant. Jon did a summer placement with Waldemar and his undergrad project in my lab. I was very impressed with Jon and was delighted he was willing to do a PhD with me. I said to Jon his project could be funded by BBSRC, requiring that he did a PIP (Professional Internships for PhD Students) or the Faculty in which case the three month break was not required. Jon said “I want to do science during my PhD and not be distracted by other activities”. Ana wanted to do a PhD with a glycan lab and came highly recommended by one of my previous PhD students, Carlos Fontes from the University of Lisbon, Portugal. So Ana is doing a three year PhD with no MRes, PIPs etc. Some of us, of a certain age, may remember these type of PhDs.

The two students have worked on glycan degradation by the human gut microbial community, or microbiota. Jon is focussed on the biochemistry of selected enzyme systems and the extent to which there is cross feeding of oligosaccharide products generated during the degradative process. Ana, like Jon, has used molecular genetics and biochemistry to explore the enzymology of these glycan degrading processes, while also using X-ray crystallography to study the structure and function of key enzymes.

The two students have worked on glycan degradation by the human gut microbial community, or microbiota. Jon is focussed on the biochemistry of selected enzyme systems and the extent to which there is cross feeding of oligosaccharide products generated during the degradative process. Ana, like Jon, has used molecular genetics and biochemistry to explore the enzymology of these glycan degrading processes, while also using X-ray crystallography to study the structure and function of key enzymes.

Both students are remarkable in that they work on their own project within a largish collaboration. This is fine but on a regular basis, well almost weekly, they are given “the opportunity” by their supervisor to alter the objectives of their project almost on a weekly basis. They adapt to these unusual demands brilliantly. We all have tremendous respect for both students; they work extremely hard, are technically excellent, flexible and, most importantly, think carefully about their science, designing and carrying out a series of decisive experiments to resolve critical components of the glycan degrading process. Maybe the best testimony I can provide is that it is not possible to distinguish Ana and Jon from the postdocs in the lab, they are an inspiration to all of us.

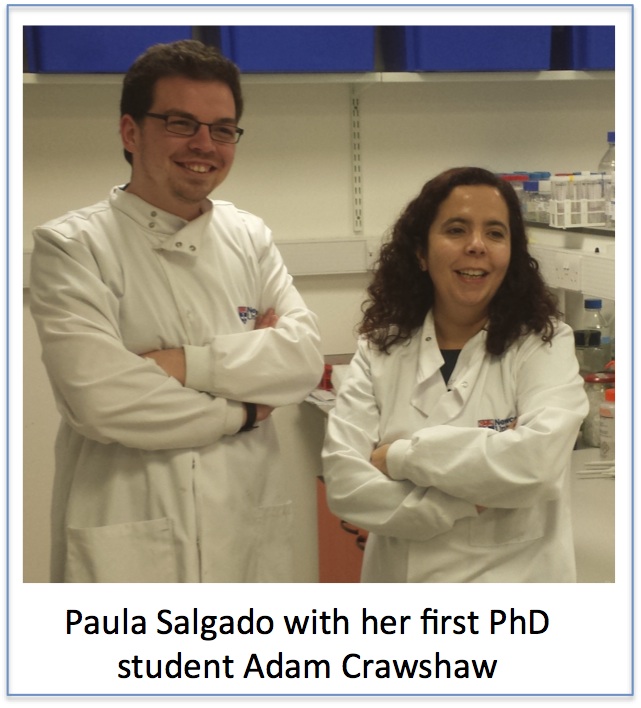

Paula Salgado: Adam Crawshaw

Being your supervisor’s first PhD student can be a mixed bag. You will get a lot of their attention, so help will always be available. But at the same time, as they find their way as independent researchers, any issues will be closer to your own progress than for many of your colleagues. As I saw Adam present his work at the ICaMB Postgraduate Research Symposium, I was reminded of my own journey as a “first student”, several years ago. As I shared my supervisor’s progress, so has Adam shared mine. It has been fantastic seeing him develop, visibly learn and acquire so many skills. Even when his project didn’t go according to plan and experiments were proving hard, he didn’t lose the drive, the enthusiasm. It was with pride that I saw him give a confident talk, answer questions and be humble enough to challenge his own work. He has learned many techniques, from crystallography to circular dichronism, from molecular biology to NMR – he took it all in willingly and enthusiastically. His contribution to understanding several aspects of Clostridium difficile pathogenicity will be in the scientific papers produced, as well as in the future of my “Structural Microbiology” lab. It was great to hear him present all the work he did over the last 3.5 years to our colleagues. Well done!

Dianne Ford: Joy Hardyman

Joy Hardyman’s presentation at the ICaMB Postgraduate Student Research Symposium was on the topic of zinc, which we have studied in our lab for many years. Joy’s PhD research is funded by an MRC studentship, which not only gave Joy the opportunity for research training but also really allowed us to add value to data we collected as part of a BBSRC grant, and generated an additional publication (Hardyman JEJ et al (2016) Metallomics (in press)).

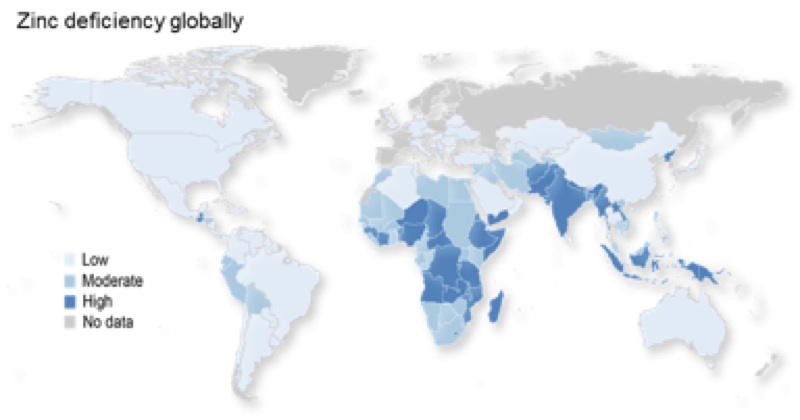

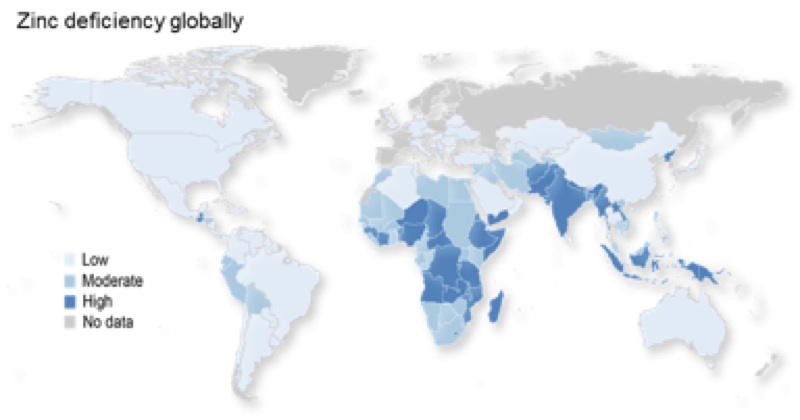

The lab’s focus is the basic cell biology of zinc, which is essential to understanding zinc nutrition. Zinc nutrition is a global health challenge, with an estimated 17.3% of the global population at risk of inadequate zinc intake. Also older people, including here in the UK, are particularly at risk of sub-optimal zinc intake or low plasma zinc concentrations.

The lab’s focus is the basic cell biology of zinc, which is essential to understanding zinc nutrition. Zinc nutrition is a global health challenge, with an estimated 17.3% of the global population at risk of inadequate zinc intake. Also older people, including here in the UK, are particularly at risk of sub-optimal zinc intake or low plasma zinc concentrations.

At the end of our BBSRC grant we had some intriguing microarray data that we had set aside because we struggled initially to make sense of it. We had depleted cells of a transcription factor known to have a role in zinc homeostasis (MTF1) then challenged them with zinc, with the aim of identifying the gene targets of this transcription factor. However, rather than see gene responses to zinc being attenuated we saw ‘sensitisation’ of the transcriptome response to zinc. We now know that this is because the usual response of the intracellular protein metallothionein, which effectively ‘mops up’ intracellular zinc, was attenuated because this response is under the control of MTF1.

At the end of our BBSRC grant we had some intriguing microarray data that we had set aside because we struggled initially to make sense of it. We had depleted cells of a transcription factor known to have a role in zinc homeostasis (MTF1) then challenged them with zinc, with the aim of identifying the gene targets of this transcription factor. However, rather than see gene responses to zinc being attenuated we saw ‘sensitisation’ of the transcriptome response to zinc. We now know that this is because the usual response of the intracellular protein metallothionein, which effectively ‘mops up’ intracellular zinc, was attenuated because this response is under the control of MTF1.

Interestingly, we now think this model, where MTF1 is depleted, may allow us to study what happens to zinc homeostasis in cells as they age, because cells from older individuals have higher levels of metallothionein. Thus, cells with MTF1 depleted may represent a ‘younger’ phenotype. We will now explore the suitability of this as a model of zinc balance in the ageing cell with a view to using it in further research to gain a better understanding of zinc dys-homeostasis in older age.

Interestingly, we now think this model, where MTF1 is depleted, may allow us to study what happens to zinc homeostasis in cells as they age, because cells from older individuals have higher levels of metallothionein. Thus, cells with MTF1 depleted may represent a ‘younger’ phenotype. We will now explore the suitability of this as a model of zinc balance in the ageing cell with a view to using it in further research to gain a better understanding of zinc dys-homeostasis in older age.

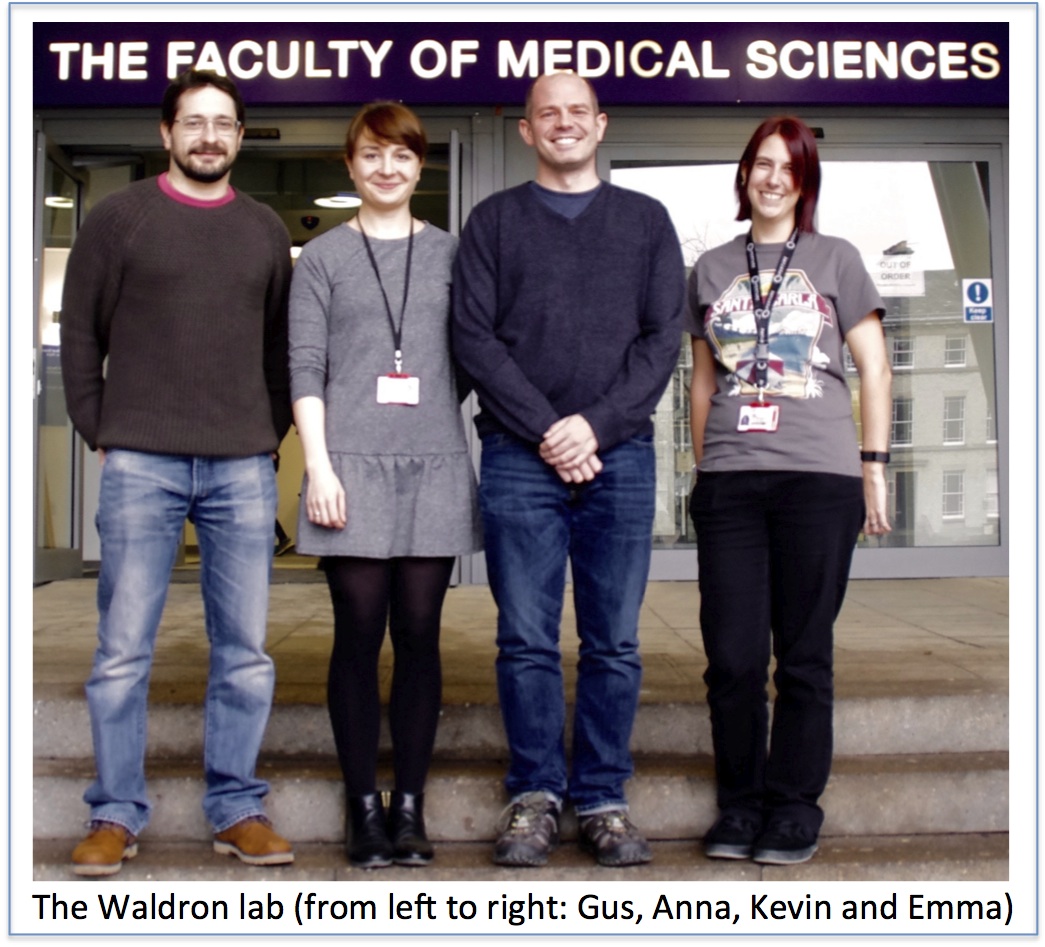

Kevin Waldron: Anna Barwinska-Sendra

Anna’s project began as something of a ‘sideline’ of research in my lab, something that I’d originally initiated when I first started my own independent research back in 2010 but then put on the back burner due to limited resources when my ‘lab group’ consisted solely of me. I re-initiated the project when Anna approached me for a short period of work experience in my lab in 2012. It is a tribute to Anna’s drive and enthusiasm that, within just a few days of her being in my lab, I was keen to keep her on in some form, and I was delighted when she later accepted my offer of a PhD studentship to continue this project in my lab. It’s one of the best decisions I’ve made in my short time as a PI.

I set Anna the task of determining the metal specificity of the two superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes that are encoded within the genome of Staphylococcus aureus. SODs are essential for the bacterial defence against the reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide anion, and both of these enzymes were predicted to be manganese-dependent. However it was emerging that, during infection, pathogens such as S. aureus experience host-imposed manganese starvation, a process termed nutritional immunity, which raised the possibility that one or both of these enzymes might be able to use an alternative cofactor for catalysis, most likely iron. Anna has confirmed that one of these enzymes is cambialistic in vitro, which means it is catalytically active with either metal cofactor, something that’s exquisitely rare amongst metalloenzymes. We hypothesise that this cambialistic property of this SOD is a mechanism by which S. aureus is able to circumvent nutritional immunity and resist the onslaught of oxidative attack during manganese starvation.

Anna has been an exceptionally productive student during her time in my lab, and I’ll be sorry to lose her when she completes her studies later this year. She has a bright future in research. Her project also highlights the importance of PhD student projects to a ‘basic research’ lab like mine, as they enable more exploratory, high-risk, high-reward projects such as this, and allow us to take our research in whole new directions that would not be possible within the constraints of traditionally-funded, Research Council grant-based projects.

Jeremy Lakey: Alysia Davies

Alysia’s studentship is rather unusual as it is funded by the BBSRC, Bioprocessing Research Industry Club (BRIC) and has a partner company, Pall, who make a huge range of products used in the production and purification of biomolecules. BRIC is a very proactive organisation that meets twice a year for students and post docs to present their work. It also arranges training and skills schools to enhance the employability of the graduates especially those wishing to enter the fast growing bioprocessing industry. This industry is responsible for delivering the next generation of treatments based upon large protein and DNA molecules rather than small molecules such as penicillin. The magic bullets in all this are immunotherapies based upon large proteins called monoclonal antibodies. These are used in the treatment of many conditions such as cancer (Avastin) or rheumatoid arthritis & Crohn’s Disease (Humira). One difference with such large molecules is that they can provoke an immune response which prevents further treatment. Such responses are more common if the proteins stick to each other; a process known as aggregation. Alysia’s project is to develop rapid tests for aggregation so that problem batches can be detected early in the factory and removed. We hope these tests will make the medicines both safer and cheaper.

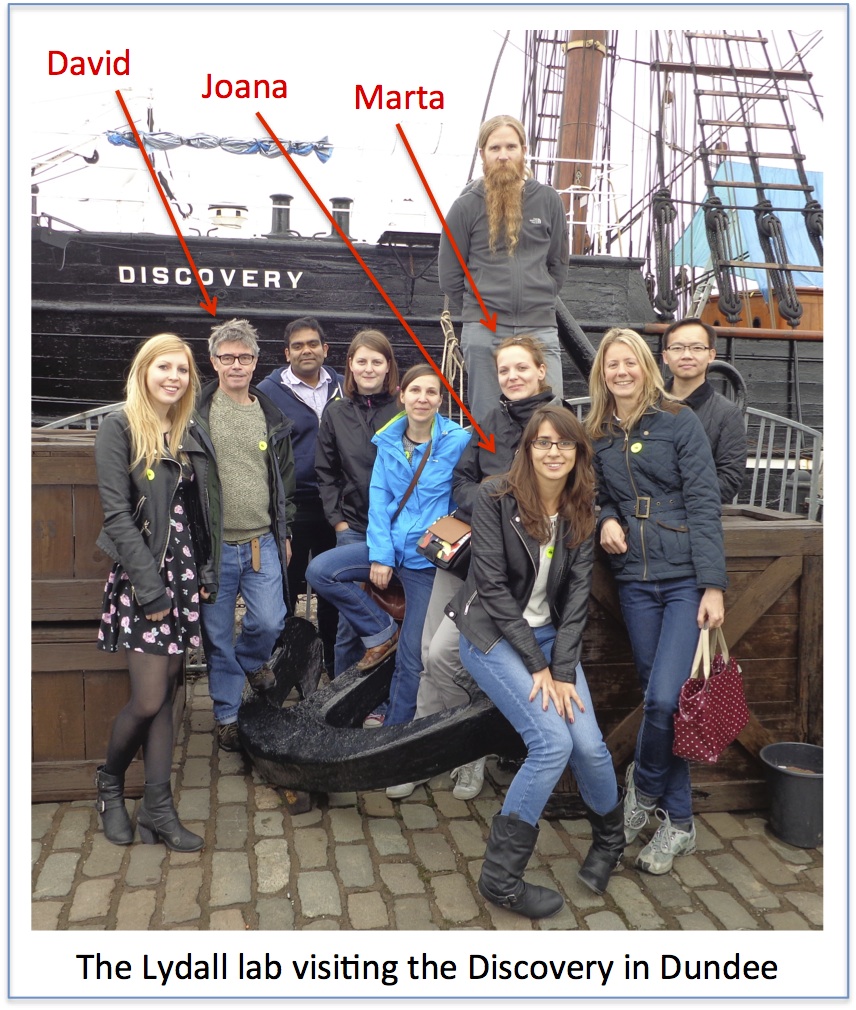

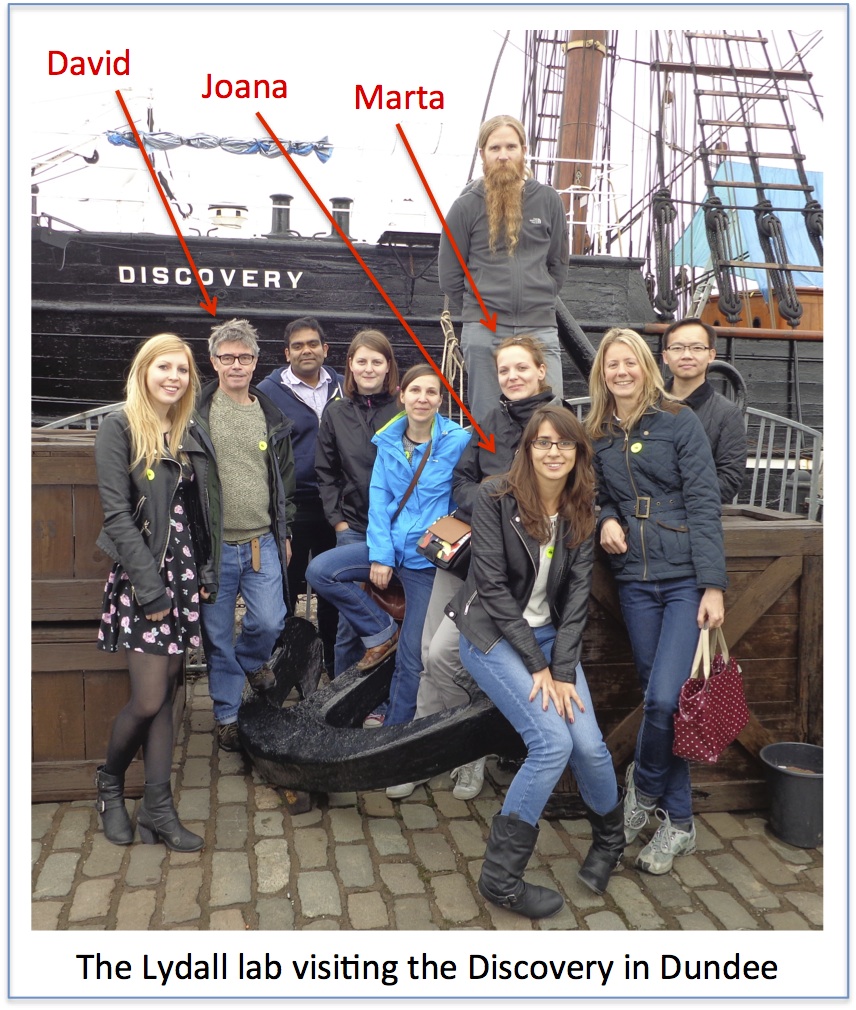

David Lydall: Joana Rodrigues and Marta Markiewicz

Joana Rodrigues, from Portugal, and Marta Markiewicz, from Poland, will complete their EU (Marie Curie) International Training Network funded PhDs very soon. On this basis I will vote to stay in Europe.

As a supervisor I have been delighted to have Joana and Marta in my lab. It is really rewarding to have bright, enthusiastic, international members of the lab. Very often the most rewarding aspect of my job is observing PhD students gain confidence, experience and strength during their comparatively short time in the lab. I think this has certainly been the case for Joana and Marta and they both gave excellent talks at the symposium.

As is usual, at least in my lab, the projects Marta and Joana have pursued have drifted substantially from where they started. It is one of the most fun aspects of supervising PhD students that there are few, if any, “milestones” to be met during a PhD. Despite this chaos, philosophy usually occurs, doctorates are earned and knowledge improves.

Joana and Marta have each worked in budding yeast on proteins that are conserved in human cells and that affect cancer. Joana has made substantial inroads to our understanding of how the PAF1 complex interacts with and affects telomere function. Marta has shown how Dna2 protein, known to be important for DNA replication, may play its most important functions at telomeres. We are just in the process of submitting papers from both Marta and Joana. They have also each agreed to stay in the lab for a further year to capitalize on all their hard work.

Joana and Marta were recruited to the Codeage International Training Network, which is centred in Cologne (http://itn-codeage.uni-koeln.de). For all three of us this was our first involvement in such a network. It has been a lot of fun and we have networked our way from Cologne, to Crete and Milan. We are looking forward to the final meeting in Crete in September.

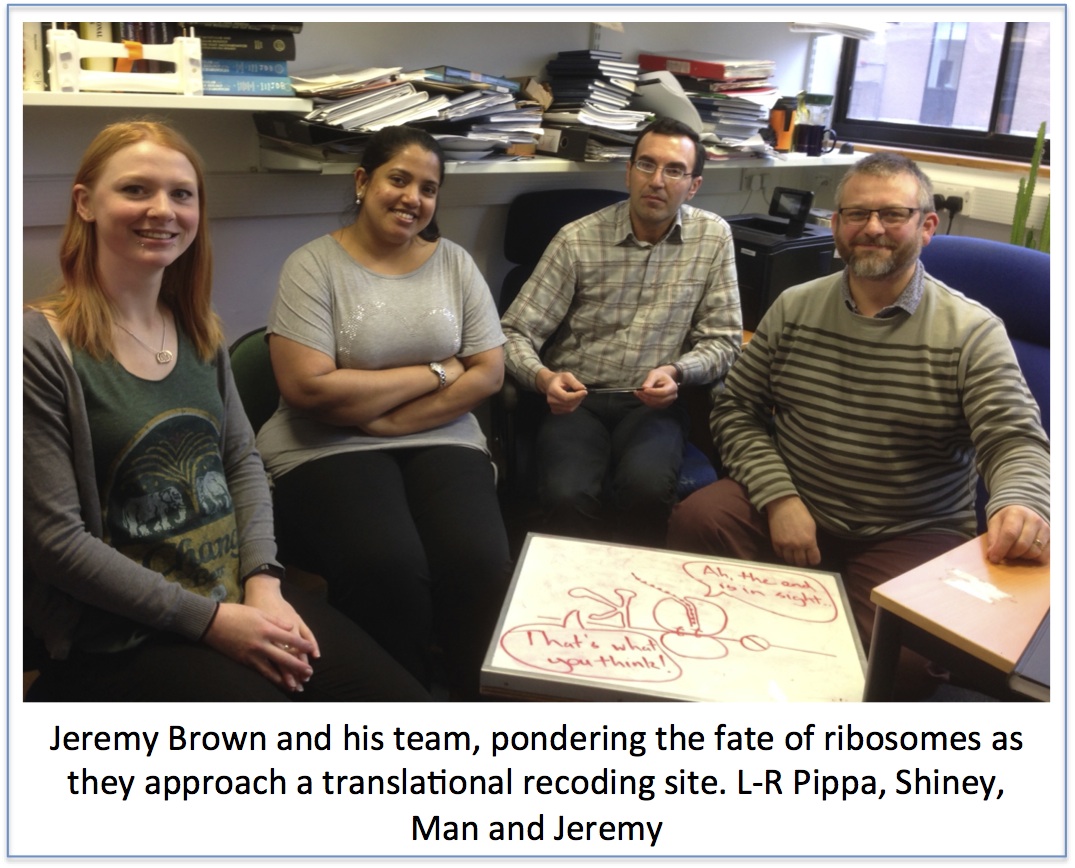

Jeremy Brown: Shiney George and Man Balola

I have 3 PhD students in the final year of their studies. 2 of them, Shiney George and Man Balola gave excellent presentations on their work on translational control of viral gene expression in the Symposium earlier this week. My lab has been dependent on PhD students for the last few years, and I can only thank them for the positive contribution that they have all made to the lab’s research output: without them there would have been little, if any, progress. Nearly all the lab publications in the last few years have had PhD students as first authors, and the current group have generated excellent data for the next papers that we will publish.

My students over the past few years have had very different sources of support, from self-funded through sponsored to Research Council support. This has led me to reflect on the disparities between funding arrangements, and also how this and the structure of PhDs has changed over the years. I was very lucky when I did my PhD – I was the recipient of a Welcome Trust Prize Studentship. These were quite a novelty at that time, a relatively new scheme, with more generous stipend than other studentships, but the same length – 3 years – as most other studentships. At that time pretty much all PhDs were: go to the lab; do the work; learn the trade; write the thesis.

In the years since my time as a PhD student there has certainly been a shift in how PhDs are organised with alterations to funding for students, various add-ons in terms of knowledge and skill training being tried and in some cases discarded, and a move towards longer, 4 year, training. Some of this could be argued to have diluted the important ‘learn the trade’ part of a PhD, though there are clear pros to enhanced training too. Perhaps more worrying though, there is considerable disparity in the provision for students funded from different sources. One obvious issue is the budget for laboratory costs, which is woefully inadequate for many studentships, but much more adequately costed from others. This has to impact at some level the ambition and scope of PhD projects. Another issue is that while the formal length of PhD (i.e. the time from starting to when the book has to be submitted) is pretty much standard at 4 years, there are differences in the length of funding of PhDs. As we know, as staff in ICaMB we can apply for 4 year BBSRC studentships, 3½ year MRC, and faculty studentships (including this year the Research Excellence Academy) that provide 3 years.

There are few level playing fields in life, but as a PhD is an academic qualification one might naively expect that the duration, resources and other support should, where possible, be similar, at least within a country. Why are there such disparities, how confusing must this be for anyone hoping to employ someone with a PhD? Bioscience needs bodies and PhD students are the backbone and key work-force of a good number of laboratories (mine included). There is then strong competition between academics for studentships each year – evidenced particularly by the very large number (>150) of applications for faculty studentships this year – and disappointment for those who are unsuccessful. Conversely there are many aspiring to a career in bioscience for whom a PhD is a key step. So, there are strong reasons to spread the available resource as broadly as possible, and it is easy to rationalise the way in which resources are being used. I would make the comment (my personal view) that at a time when significant efforts being made to even out opportunities at a number of career stages, we should when possible make sure that we do not undermine this at the early stages, by having some PhD students advantaged over others. And this is before the vagaries of supervision, luck and other factors kick in.

I began my academic career as an undergraduate student at Sheffield University in 1973, I finish as the Professor of Biochemistry at Newcastle in 2016. Possibly the biggest change to have occurred over this forty or so years is the degree of surveillance and monitoring to which everybody at the University is subject. During my undergraduate studies attendance at lectures was voluntary and it was up to me to decide if, and when, I should consult my tutor. While a PhD student and postgraduate there was no concept of mandated and recorded meetings with my supervisors and the only reports I was expected to prepare were first drafts of eventual publications. When starting as a lecturer at Southampton University, I had about five minutes with the Head of Department, was shown an office and left to get on with it. I had no formal meetings with my “line manager” (indeed this concept did not exist) and I was prepared for undergraduate teaching with a single three hour session. Today undergraduate attendance at lectures is recorded as are compulsory meetings with tutors; sanctions are applied for non-compliance. PhD students have multiple supervisors/mentors and are required to record compulsory meetings with them. A number of intermediate reports must be produced and assessed along the road to graduation with a doctoral degree. Staff have a PDR once a year and are required to complete forms detailing the work they perform and how they occupy every hour at, and away from, work. Although I personally prefer the old system, this article is not aimed at discussing which is better. Rather, it is to enquire how the University implements policy changes, often introduced at the cost of great disruption, to ensure they are based on best current practice. Further, how are the outcomes of these changes determined and any benefits measured?

I began my academic career as an undergraduate student at Sheffield University in 1973, I finish as the Professor of Biochemistry at Newcastle in 2016. Possibly the biggest change to have occurred over this forty or so years is the degree of surveillance and monitoring to which everybody at the University is subject. During my undergraduate studies attendance at lectures was voluntary and it was up to me to decide if, and when, I should consult my tutor. While a PhD student and postgraduate there was no concept of mandated and recorded meetings with my supervisors and the only reports I was expected to prepare were first drafts of eventual publications. When starting as a lecturer at Southampton University, I had about five minutes with the Head of Department, was shown an office and left to get on with it. I had no formal meetings with my “line manager” (indeed this concept did not exist) and I was prepared for undergraduate teaching with a single three hour session. Today undergraduate attendance at lectures is recorded as are compulsory meetings with tutors; sanctions are applied for non-compliance. PhD students have multiple supervisors/mentors and are required to record compulsory meetings with them. A number of intermediate reports must be produced and assessed along the road to graduation with a doctoral degree. Staff have a PDR once a year and are required to complete forms detailing the work they perform and how they occupy every hour at, and away from, work. Although I personally prefer the old system, this article is not aimed at discussing which is better. Rather, it is to enquire how the University implements policy changes, often introduced at the cost of great disruption, to ensure they are based on best current practice. Further, how are the outcomes of these changes determined and any benefits measured?

asked if they found the scheme helpful. This paper could be used as an example of how not to do science and I can only assume that the author, a young medical doctor, felt that any publication, no matter how poor, would benefit his future career. The second was not even peer reviewed, rather a trenchant statement of a scheme supporter bereft of any evidence. The purpose of the buddying is assuredly to improve undergraduate teaching and, as we survey our students almost to destruction, I enquired if an improvement in quality had been observed. I received no reply and concluded that this scheme was started on the whim of the dean involved, based on little evidence and with no mechanism in place to observe its consequences. This example is trivial but similar considerations apply to the much more consequential issues addressed in the first paragraph. I have yet to be presented with evidence that constant monitoring and assessing of students and staff is based on rigorous studies that clearly demonstrate positive effects. We survey our undergraduates continually and for postgraduates and postdoctoral workers have data on their accomplishments (do PhDs graduate on time, how many publications result from

asked if they found the scheme helpful. This paper could be used as an example of how not to do science and I can only assume that the author, a young medical doctor, felt that any publication, no matter how poor, would benefit his future career. The second was not even peer reviewed, rather a trenchant statement of a scheme supporter bereft of any evidence. The purpose of the buddying is assuredly to improve undergraduate teaching and, as we survey our students almost to destruction, I enquired if an improvement in quality had been observed. I received no reply and concluded that this scheme was started on the whim of the dean involved, based on little evidence and with no mechanism in place to observe its consequences. This example is trivial but similar considerations apply to the much more consequential issues addressed in the first paragraph. I have yet to be presented with evidence that constant monitoring and assessing of students and staff is based on rigorous studies that clearly demonstrate positive effects. We survey our undergraduates continually and for postgraduates and postdoctoral workers have data on their accomplishments (do PhDs graduate on time, how many publications result from  their work, what are their future job successes). But this data is never correlated with policy changes to measure their efficacy. Similarly for staff, following the introduction of PDR, has teaching improved, has grant funding increased, have more and better publications resulted? Overall is the University a better place in which to work, perhaps monitored by absenteeism rates, which correlate well with staff happiness. As academics we must insist that anybody introducing new policies should present the evidence underpinning the change. A system for monitoring outcomes, which places minimal burden on students and staff, should be demonstrably in place. While benefits at the individual level may be small they should surely be apparent over the entire University body. Finally anybody introducing procedures based on little evidence or not leading to favourable outcomes should rapidly be removed from any position of authority.

their work, what are their future job successes). But this data is never correlated with policy changes to measure their efficacy. Similarly for staff, following the introduction of PDR, has teaching improved, has grant funding increased, have more and better publications resulted? Overall is the University a better place in which to work, perhaps monitored by absenteeism rates, which correlate well with staff happiness. As academics we must insist that anybody introducing new policies should present the evidence underpinning the change. A system for monitoring outcomes, which places minimal burden on students and staff, should be demonstrably in place. While benefits at the individual level may be small they should surely be apparent over the entire University body. Finally anybody introducing procedures based on little evidence or not leading to favourable outcomes should rapidly be removed from any position of authority.

The two students have worked on glycan degradation by the human gut microbial community, or microbiota. Jon is focussed on the biochemistry of selected enzyme systems and the extent to which there is cross feeding of oligosaccharide products generated during the degradative process. Ana, like Jon, has used molecular genetics and biochemistry to explore the enzymology of these glycan degrading processes, while also using X-ray crystallography to study the structure and function of key enzymes.

The two students have worked on glycan degradation by the human gut microbial community, or microbiota. Jon is focussed on the biochemistry of selected enzyme systems and the extent to which there is cross feeding of oligosaccharide products generated during the degradative process. Ana, like Jon, has used molecular genetics and biochemistry to explore the enzymology of these glycan degrading processes, while also using X-ray crystallography to study the structure and function of key enzymes.

The lab’s focus is the basic cell biology of zinc, which is essential to understanding zinc nutrition. Zinc nutrition is a global health challenge, with an estimated 17.3% of the global population at risk of inadequate zinc intake. Also older people, including here in the UK, are particularly at risk of sub-optimal zinc intake or low plasma zinc concentrations.

The lab’s focus is the basic cell biology of zinc, which is essential to understanding zinc nutrition. Zinc nutrition is a global health challenge, with an estimated 17.3% of the global population at risk of inadequate zinc intake. Also older people, including here in the UK, are particularly at risk of sub-optimal zinc intake or low plasma zinc concentrations. At the end of our BBSRC grant we had some intriguing microarray data that we had set aside because we struggled initially to make sense of it. We had depleted cells of a transcription factor known to have a role in zinc homeostasis (

At the end of our BBSRC grant we had some intriguing microarray data that we had set aside because we struggled initially to make sense of it. We had depleted cells of a transcription factor known to have a role in zinc homeostasis ( Interestingly, we now think this model, where MTF1 is depleted, may allow us to study what happens to zinc homeostasis in cells as they age, because cells from older individuals have higher levels of

Interestingly, we now think this model, where MTF1 is depleted, may allow us to study what happens to zinc homeostasis in cells as they age, because cells from older individuals have higher levels of

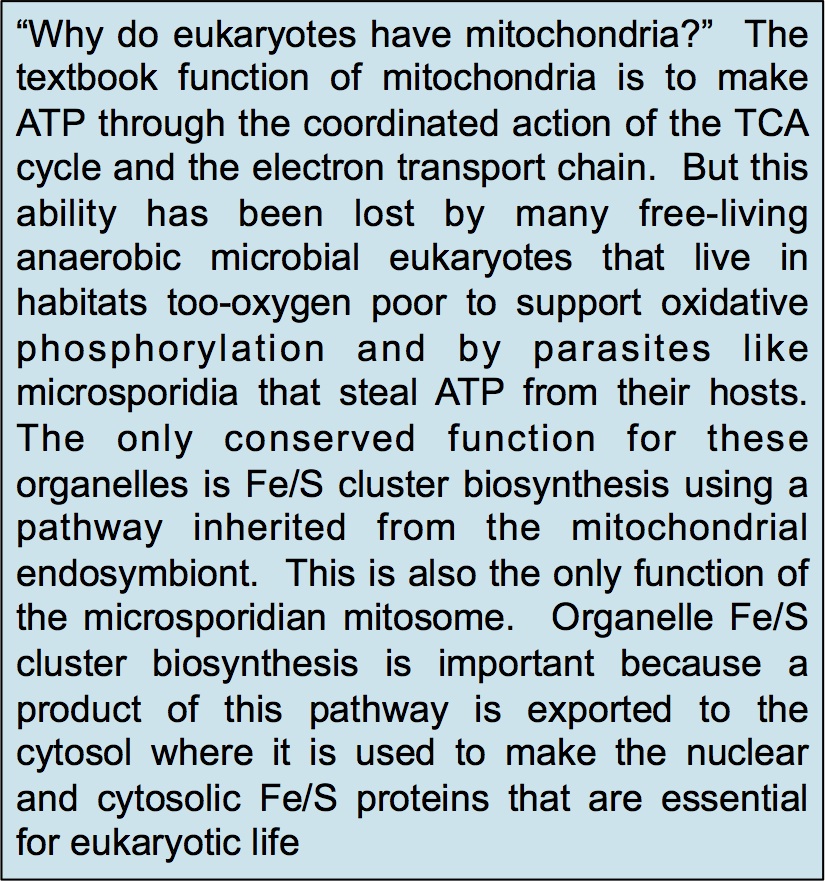

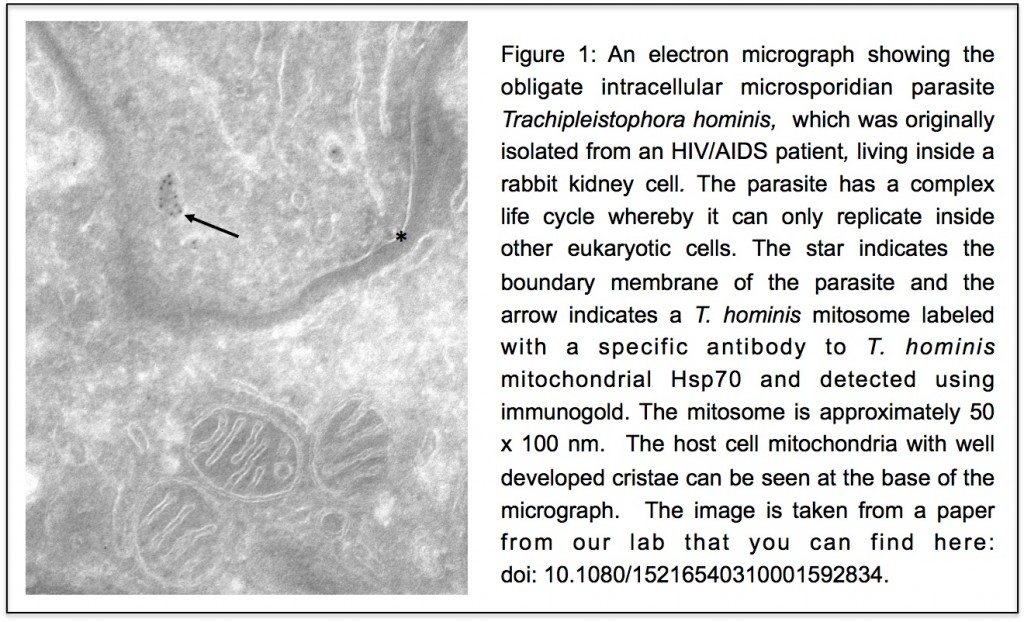

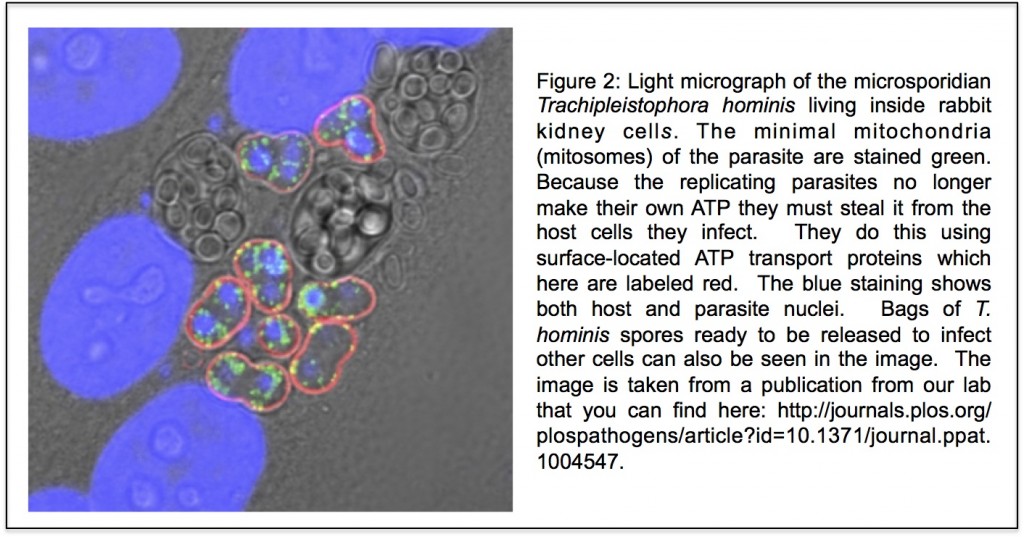

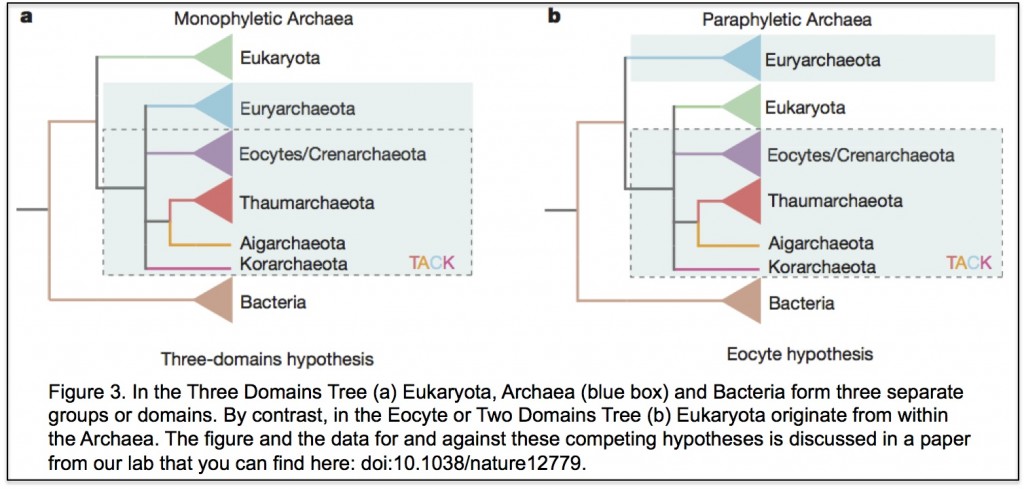

to work on the early evolution of eukaryotic cells. At the time two ideas were central to views of early eukaryotic evolution. One was that the “three domains tree of life” was an accurate description of the relationships between eukaryotes and prokaryotes (you can see the tree

to work on the early evolution of eukaryotic cells. At the time two ideas were central to views of early eukaryotic evolution. One was that the “three domains tree of life” was an accurate description of the relationships between eukaryotes and prokaryotes (you can see the tree  y together but Robert and I co-supervised PhD student Bryony Williams who showed that

y together but Robert and I co-supervised PhD student Bryony Williams who showed that