A new guide has been created in the Humanising the Online Experience area on the FMS TEL Canvas Community, and can be accessed directly. You can download this document to keep a summary of the webinar tips handy, or read it below. If you can’t access the FMS TEL Canvas community, please enrol yourself before retrying the direct link.

Humanising the Online Experience

This document summarises the tips from the FMS TEL Humanising the Online Experience webinar. The full set of resources can be found on the FMS Community, including rationale, research, and links to resources. This should be read in conjunction with the University guidance and the guidance available within your school. Not all tips will be useful for all situation or all students – you know your students and can select appropriate strategies.

Objectives

- know how to set expectations and maintain these

- have strategies to make synchronous sessions more like PiP interaction

- have strategies to be more present in non-synchronous aspects of a course

Summary

- Humanise your teaching by being compassionate to your students and yourself.

- Set clear and reasonable expectations, and be predictable.

- Know your student (‘s names)!

- Ensure student contributions are easy to make and clearly valued.

- Be authentic rather than perfect – acknowledge the awkwardness and tech troubles.

- Create opportunities for regular quality authentic interactions with students.

- Appreciate the strength of video and live interaction in terms of richness of interaction, while noting that this makes it more intense to participate in.

- Recognise the benefits of non-synchronous activities in reducing pace and intensity, allowing for more reflection and considered responses, and bridging time zones.

Expectations

Learning online is a change of culture and this needs to be recognised. Students and staff are still negotiating how the classroom works in an online context and sometimes there is a misalignment between staff and student expectations.

Expectations and Assumptions

Remember that your session may not be the only session that students are attending that day. Acknowledge the challenges of the online way of working and work with students to adapt to these. Consider:

- A poll or survey to check what is going on with students.

- Reach out to learners who are not engaged or are not progressing.

- Discuss how to adapt to the online environment.

- Draft a Group Learning Agreement together and share your expectations clearly.

Make it easy for students to access your session by being predictable. Repeat similar task/session structures and activities to cut down on instruction time.

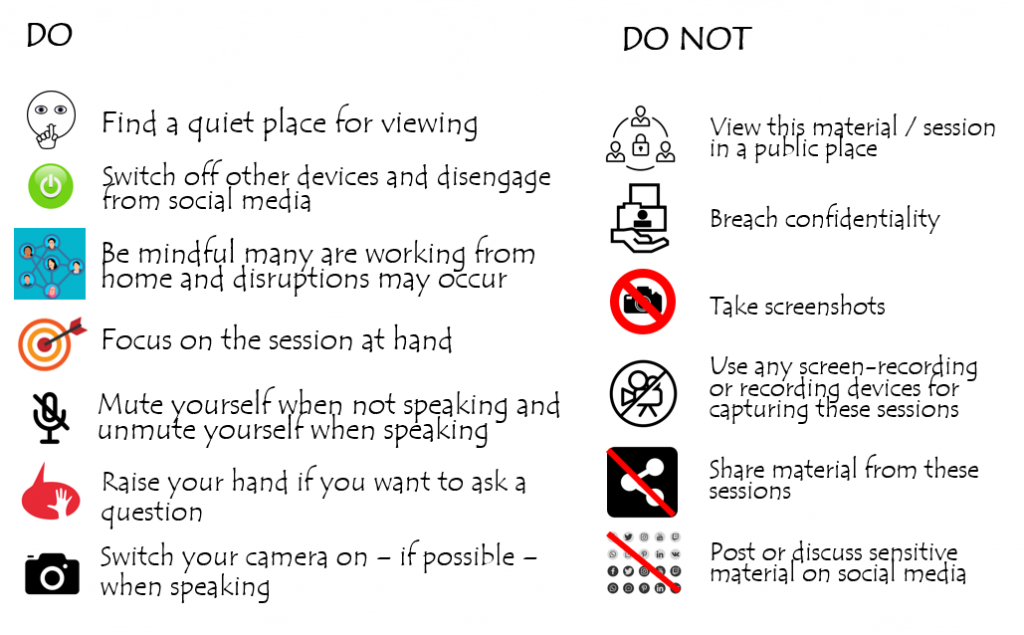

Maintaining Expectations

Consider using a holding slide at the start of each session with session expectations on it. Repeating these helps remind students of the required standards. Include/be mindful of caveats. For example, instead of ‘Students must have cameras on at all times’ try ‘Students should keep cameras on where possible’. Encourage through gentle nudges – thanking students for complying rather than taking an ‘enforcer’ stance. Lead by example wherever possible.

Synchronous Strategies

Camera Off

You can use these camera breaks for any type of task, such as considering an answer to a question or looking at a new resource and responding. Make sure that you use clear start and end points, stay silent for some time yourself, and warn students before feedback or further input starts. If students don’t have to worry about how they appear on the camera, they can more effectively concentrate on the task. Camera-off time allows for moments away from the emotional stress of being ‘under scrutiny’, and it eases screen fatigue if the student has had other classes prior to yours.

Explain that camera-off time will be included in your session introduction and expectations. This mitigates the problem of people thinking they need to choose on or off at the beginning of the session and then stick to it, making ‘camera on’ a much less intimidating choice and allowing an easy way in for shy students.

Hide Self View

If you find your own image distracting, click on your image in Zoom and choose ‘hide self’. Note students do need to be warned that this doesn’t hide others from seeing them! This feature is not yet available in Teams, but you can always stick a post-it on your screen!

Chat

Asking students to drop their responses in the chat box allows shy students to participate more easily and allows those who prefer to learn through discussion to do that without taking over the session. Students can go back and review the chat if it is saved for them too. This is quicker than setting up a shared document.

Authenticity

Acknowledge the awkwardness of video teaching and that you understand their awkwardness too – we’re all in it together and may need to push out of comfort zones. Be animated and show your personality/humour a little – it’s OK to smile or make jokes. People always come across ‘flatter’ on screen than in person, so the extra effort is worth it. Admit if things are a little tricky or go wrong and take a moment to fix them before moving on smoothly. Suggest a five-minute break if the whole session has been halted for tech reasons so that you can fix the problem and regroup your thoughts. Have a question or little task for students in your back pocket in case of difficulties.

Icebreaking

Icebreakers almost always feel contrived but still work – acknowledge this and be encouraging as you try these activities out. Try these in small groups in breakout rooms first. You will likely need to visit the rooms and push the energy levels up initially. Whole group icebreakers can include things like asking everyone to send a reaction emoji or give you a thumbs up/down on camera in response to questions.

Wait Time

Teachers are often guilty of not waiting long enough for an answer – usually overestimating the time they have waited. This wait time feels worse in the online environment. You need to wait longer than normal online because it takes time for students to type a response or switch on their microphones. Give a long wait time for your questions and use a timer (either on screen or silently on your phone/another screen) to make sure you are giving students enough time to respond. Lengthen your wait time if students haven’t responded, and state that you are giving them more time.

Acknowledge Individuals

Start the room early and greet students as they arrive in the room – a simple hello and using the students’ names is a lovely start! Ask students to set profile pictures on Zoom (not necessarily of themselves) to help differentiate them visually if they don’t put their cameras on. This makes them more memorable individually than a sea of names in text. Explain why you are doing this. Make effort to learn and use students’ names as you would in PiP. That doesn’t necessarily mean picking on students for questions, it can be thanking them for contributions and greeting them too. Suggest students do a video/audio introduction either privately or in a shared discussion space.

Have we started? Are we done?

Normally this is done non-verbally or with body language like standing up and coming to the front or packing away notes. Clearly announce the start and end of the class time. Consider leaving the room open for a little while after class for less formal chat.

Breakout Room Strategies

Set expectations: What do they need to achieve? By when? When will you check in with them? Warn students if/how you will do this and be consistent.

Use monitoring strategies as in PiP. Visit each breakout room quickly at the start to check everything is understood, say when you will visit again and follow up. You do not always have to contribute ‘in person’ by dropping into the room – you can also drop comments and annotations on the page. Some tasks can be monitored by a Sharepoint folder in tile view to watch multiple documents being updated simultaneously. You can’t read text, but you can set up documents with visually distinctive features such as empty boxes to be filled, or items to be sorted/moved around on the page. You can also monitor web tools and documents for each group by opening each group’s document or page in a new tab in your browser and clicking between, or even tiling them in separate windows if you have enough screen space.

Non-Synchronous Strategies

In addition to the above strategies, some of which apply in a non-synchronous setting, the tips below are unique to the non-synchronous environment.

Presence

Maintain an online presence by regularly participating in discussions and giving feedback. Show students that their discussion board posts etc. are being read by someone. This doesn’t mean always being available; it just means setting aside some time to connect. Consider running an ‘office hour’ drop-in via Teams, Zoom, or Canvas chat.

Text-based interactions

Bear in mind that tone is more difficult to convey in writing than in person. Supplement your text with emojis where appropriate or if you think there is a chance of misinterpretation. If a message seems impolite consider differences in culture and language usage – English has a tendency to be full of pleases and thank yous in a way that other languages aren’t.

Scheduling, planning, linking

Ensure that non-synchronous tasks are part of the flow of learning and that the knowledge gained is referred to in synchronous sessions. Create clear learning objectives with completion linked to synchronous events or certain dates, and make sure you feed back on them. This gives the learning more value. Set time aside to clear up issues arising from non-synchronous teaching if needed.