The cross-university LTDS Flexible Learning 2020 course has information for everyone on copyright at this link. But there are some aspects likely to be more specific for FMS which are discussed here.

Copyright is the legal right of the creator of an original work to the exclusive rights for its’ use and distribution. It does not protect an idea though, just the expression of an idea whether they are in the form of a journal article, a book, an image, a video or any other media.

This means that you may not indiscriminately use any image or other media you find online.

Don’t run the risk of legal action; check provenance and obtain permission!

Creative Commons

When media are marked ‘Creative Commons’ or ‘CC’ this means that you are allowed to use the material with provisos according to licence type, whilst the creator retains the copyright of the material.

Creative Commons has a searchable database where you can look for materials which are legal to be used under CC licences; you can find it at this link. It covers YouTube, Wikimedia Commons and Flickr amongst others. Canvas has a searchable database of CC images, to access these select ‘Unsplash’ when you click the image icon in the text editor.

There are different types of licence which govern what you are allowed to do with the material, shown in this video:

Other free sources of images

There are several searchable databases where you can find images for use in courses. Some of these are detailed below, which may be of interest to bioscientists and medics.

Wellcome Images

The Wellcome Image library has thousands of images available under CC licences, from historical medical images through to electron micrographs. Their website is at this link.

Getty Images

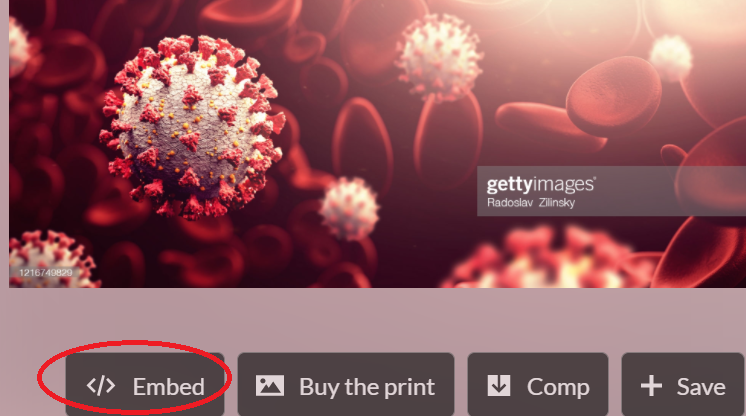

Some Getty Images are available for free via this link.

You will need an account, and you are only allowed to embed certain editorial images for non-commercial use; however there are still plenty to choose from! The embed option (</>) is present when you click on the image if you are allowed to use it; see red circle in image below:

Copy the embed code and paste into Canvas.

Images without an embed code must be paid for.

Radiopaedia

This provides a huge collection of X-rays which can be used for free, as well as articles and diagrams. The website is at this link.

Public domain

Some materials are in the public domain which means they can be freely used. It is polite to attribute these materials to their author.

Most images created by employees of the USA government are in the public domain, e.g. those from the National Institutes of Health.

Some materials are so old that the copyright has run out (more than 70 years). A good example of this is Gray’s Anatomy, available online at this link.

Rightslink

If you cannot find a free source you will need to obtain permission for use of images. This will sometimes require a budget.

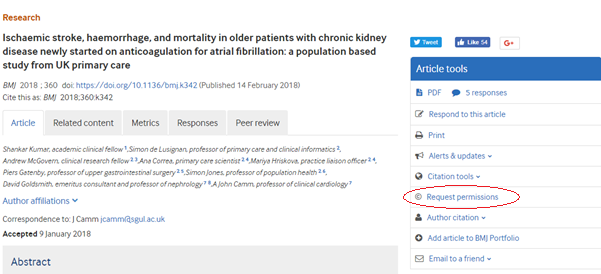

Journals which are not Open Access (most of these are Creative Commons, but do check because not all have their images as CC) often have a ‘request permissions’ button, as shown circled in red on the BMJ below.

This will take you to a Rightslink login; you can create an account for free and this will allow you to say what you want to use the image for, and what type of institution we are: despite charging for courses we are a non-commercial institution. Complete the dropdown boxes, then find out from ‘Quick price’ whether the licence is free or not, and act according to your budget. Remember to print the licence or at least store the licence electronically as well as filing the email you will be sent as well.

The licence will tell you the wording to use beside the image. An example can be found here: NATURE PUBLISHING GROUP LICENSE

Other permissions

Other permissions may be harder to obtain due to lack of attribution. If created by a named academic they can generally be tracked down to their institution and if you email them permission is often readily given; hopefully we would be as obliging if the request was made to us.