As part of the conference, Susan Lennie and Eleanor Gordon presented this video detailing the student response to the introduction.

The written summary of the development of the intervention can be accessed below.

Conference Materials – Designing Convertible Teaching

All of our posts about this conference can be seen under the tag NULTConf2022.

This workshop was presented in person for the first time at the Learning and Teaching Conference 2022. Newcastle University staff wishing to access the resources and the recording of the online version can do so here.

Looking forward to seeing you all at the Learning and Teaching Conference!

FMS TEL are well-represented at the University Learning and Teaching Conference 2022. We look forward to seeing you at the conference, and hearing what you think of our sessions, videos and posters! All of our posts about this conference can be seen under the tag NULTConf2022.

To book your place at the conference, or find out more, please visit the Learning and Teaching Conference homepage.

A written summary of our training on using rubrics with links to the full webinar resources.

We have recently delivered some training for BNS (School of Biomedical, Nutritional and Sport Sciences) in collaboration with Rebecca Gill and Susan Barfield from LTDS. The two sessions covered Rubrics – both their design and how they can be implemented in Turnitin. You can access the training recordings and resources at the foot of this page.

Examples covered included:

Rubrics can be used to evaluate assessments, whether you use a quantitative rubric to calculate marks, or a qualitative one with more wiggle room. Using a rubric makes it easier to identify strengths and weaknesses in a submission, and creates common framework and assessment language for staff and students to use. This in turn can help make learning expectations explicit to learners, and assist in the provision of effective feedback.

There is no one way to design a perfect rubric, as assessments are very individual.

Before you begin you may want to consider how you can design your rubric to lessen the marking or feedback workload. Quantitative rubrics can reduce decision-making difficulties as this means you don’t need to consider what mark to give within a band. On the other hand, you may need this flexibility to use professional judgement. A detailed rubric with less wiggle room per descriptor also acts as detailed feedback for students, reducing the need for writing long additional comments, but also takes longer to design.

When writing descriptors, ensure that there is enough clear and objective difference between each band. You may find that aligning your descriptors with an external framework helps you write them. This is critical for secure marking, and is helpful for students receiving that feedback. Using positive language also helps make this feedback easier to digest, and allows students to see what they need to include to improve.

When creating a rubric, you can follow this basic process. At every stage it is important to consult local assessment guidelines and discuss progress with your colleagues for constructive feedback.

Turnitin allows for the use of Grading Forms and Rubrics. You can watch how to implement these in the Using Turnitin video in the session resources below.

Turnitin grading forms can be created to assist with marking assignments, allowing you to add marks and feedback under various criteria. When using these forms, the highest mark entered will become the grade for the assignment. You can also use this without scoring to give feedback.

Turnitin rubrics allow for marking under multiple criteria and bands. You can have standard rubrics that calculate grades, or qualitative rubrics that do not include scoring. Custom rubrics can be used for more flexibility within a band.

An alternative to using Turnitin is to integrate a rubric into the assignment itself by using a coversheet. (see the ‘Effective Rubrics – Using Turnitin’ video at 28m25s, link in the Canvas below).

Find out the pros and cons of 360 degree meeting room cameras in practical sessions.

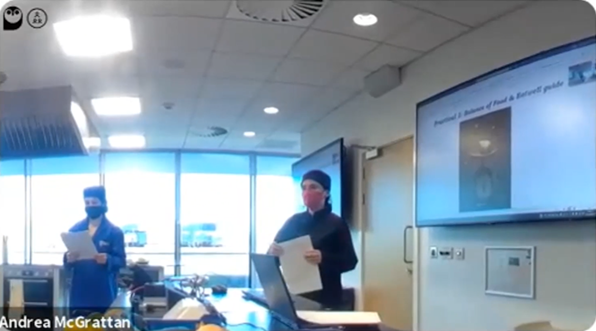

This practical session was based around students creating a meal to align with the recommendations of the EatWell guide, using ingredients provided in the food handling lab. The session involved a short introduction, followed by time for the activity, and feedback. At the last moment there was a request to record the practical session, and therefore a 360° camera was used as a quick solution – an ideal opportunity to test the camera’s capabilities.

These rooms are not set up for ReCap, so having this portable method of recording allowed for the session to be captured. The camera was connected to Zoom so that a remote student could watch the session or review the recording. As it happened, no one watched the stream live, so there was no interaction with a remote participant. As shown from the screenshots below, the camera could cover the whole room without needing to be moved. It can also zoom in and out to focus on where the action was taking place.

The camera was quick and simple to set up, and lecturers used lapel mics to capture sound when they were addressing the class. The camera was placed on the demonstrators’ bench at the front of the room, where it could see the kitchen spaces as well as the session leads, and the whiteboard.

All present were made aware of the device. It was relatively unobtrusive and didn’t get in the way of the session – most people just forgot about it. This is a bonus as it means the lecturers don’t have to consider what to capture at various points during the session. They could also walk around the room naturally rather than being stuck at the fixed point of presenting from a particular spot at the front as the camera would follow them.

As a quick solution, it was easy to set up, and the predetermined settings allowed for much of the session to be captured. It provided a record of the practical session, though due to the level of automation in where the camera chose to focus, some detail and some sound was lost. For example, on some occasions, the camera would choose to focus based on an incidental sound in the room, like a pot being scraped. This kind of auto-selection would work better in a situation such as a seminar where everyone sits around one table with less background noise and more obvious turn-taking when speaking.

The camera also captured incidental discussions – as it was placed at the front where students were collecting ingredients, it captured discussions between students about what they were choosing to include in their meal.

It was also able to capture two areas simultaneously and display them side by side, allowing for an overview of the room as well as capturing individual discussions.

There are a range of applications for this type of device in a practical setting. For example, for a remote student, the device could be placed in a group of students so that some collaboration would be possible. This would allow them to be more involved in the practical aspect of the session, though of course it would not be a complete substitution for in-person attendance.

Though the session recordings are relatively long, once uploaded to Panopto, bookmarks could be added to allow students to quickly navigate to various parts of the session, for example the input and feedback.

Roisin Devaney, Susan Lennie and Andrea McGrattan, Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Biomedical, Nutritional and Sports Sciences

Art of the Possible Lightning Talk including a brief overview of this work at 24:22.

A showcase of some of our work from 2021 and our submissions to the Learning and Teaching Conference 2022.

The FMS TEL team have collaborated on a wide range of projects throughout 2021, some of which we have submitted to the internal Learning and Teaching Conference 2022.

Staff from the School of Dental Sciences and FMS-TEL have collaborated throughout the pandemic to ensure summative assessments continue in a robust fashion to satisfy regulatory requirements. This required a flexible approach to online assessment which continues to be important as the uncertainty continues. This presentation details the challenges we have faced and solutions we have utilised, offering practical advice for those who may wish to run online exams in the future on any platform.

Sarah Rolland and Luisa Wakeling, School of Dental Sciences

Role-play and peer observation are widely used as educational methods for teaching communication skills in healthcare education, which has become a greater challenge to implement during the pandemic. In the context of dietetics and nutrition, our students developed communication skills using innovative audio resources. This video will discuss student voice survey findings regarding engagement and quality perceptions of the resources, and advise those wishing to create similar tasks, including task setup and technical support.

Susan Lennie, Biomedical, Nutritional and Sport Sciences

This workshop sets out the aims of incorporating reflective practice with scaffolded approaches in your teaching contexts and invites you to explore their potential value in your programmes or modules. Structured reflective templates are one of the key developments of the new NU Reflect system, which are currently being piloted. This session will also offer case studies to demonstrate how colleagues have implemented reflective templates to support the student reflective process within their contexts.

Patrick Rosenkranz, Simon Cotterill, Sam Flowers, David Gillies, David Teasdale

A brief look at the FMS bespoke VLE Ngage, and its special features which were designed for our distance learning programmes. This session will cover how we migrated our content into Canvas without losing functionality and the challenges we encountered. We will also discuss how the content has evolved during the pandemic and the changes made to enhance the student experience.

Emily Smith, FMS TEL

This video demonstrates a how animations can be used to demonstrate concepts in teaching. It showcases advanced animations that are used to show complex concepts and allow for dynamic and interactive content to be shared on screen. Should you not have access to high-end software, the video also shows what can be achieved using PowerPoint animations and shows some tools that can be used to develop understanding beyond static diagrams or simple videos.

Ashley Reynolds, FMS TEL

This workshop provides colleagues with practical tips on how to design teaching that can be converted between online and offline, and synchronous and asynchronous delivery styles with minimal effort. Participants will think through resource design using examples, and apply this knowledge to their own resources brought to the session. Participants will take away technological shortcuts that reduce the burden when changing delivery styles, as well as an understanding of how to design inherently flexible resources.

Eleanor Gordon, FMS TEL

This talk covers the development of a MOOC which develops students’ skills in 3D Spatial Awareness in the context of the study of anatomy. This collaboration between Newcastle University and the University of Cape Town focuses on specific art-based and technology enhanced learning exercises to develop skills that will enhance students’ capabilities in clinical observation, diagnosis, and surgical training. Prior research and development of specific observation methodologies, their deployment in an online environment, and students’ learning outcomes will be shared.

Iain Keenan, School of Medical Education

This presentation shares practice from rapid changes made to ‘flip’ learning and teaching in MB BS, in response to the pandemic. This is in the context of a new Clinical Decision Making course, originally designed to use online cases to supplement primarily face-to-face learning and teaching in both UK and NuMed. The pandemic gave need to rapidly shift to predominantly online delivery with more asynchronous delivery. We will demonstrate adaptions made and discuss lessons learned.

John Moss, David Kennedy, Dan Plummer

A study across campuses of Newcastle University into perceptions of TEL use found that staff in the NUMed and Singapore campuses felt they lagged behind in training for using TEL. The FMSTEL team responded with an online conference, collaborating with NUMed, at a time accessible to all. Various topics included specific technologies and embedding online transnational cross-campus teaching in the curriculum. Successful, it may become an annual event.

Alison Clapp, David Kennedy, Ruth Valentine, John Moss and Bhavani Veasuvalingam, FMS and NUMed

What is Canvas Commons, how does it work, and why is it useful for disseminating online learning material? I will present examples of tutorials I have shared and induction material. By using Commons we can promote our material and the University to the wider Canvas Community. This will address the theme of Changing Practice through the Pandemic by focusing on the use of Canvas to provide excellent learning opportunities.

Michelle Miller, FMS TEL

Today, Tracy and Eleanor gave a lightning talk as part of the Art of the Possible series. We shared our recent work with 3D and virtualising spaces, as well as using technology for interactive teaching when students can’t all be Present in Person.

Resources and links from the session are available below. Some may only be accessible to Newcastle University staff.

This post is about the use of Menti – a pretty polling tool that can show responses in real time on screen. Lindsey Ferrie used this to gather student feedback during an in-person event. Link to guides included.

In Biomedical, Nutritional and Sport Sciences this year there is a focus on improving assessment and feedback. Including student voice in this development work is key. As well as the normal routes for student voice, such as staff-student committees and module evaluation forms, there were certain questions that staff had in mind which could reveal a lot about how students were feeling about this aspect of their course.

The formal module evaluation forms don’t always capture a large sample from the student body, and as with any survey, generating a high response rate is very difficult, and can sometimes end up only revealing the most polarised responses. Informal live response tools were a potential way to gather large amounts of more representative data, as well as demonstrating that feedback is wanted, heard, and acted upon within a shorter cycle. It is also much more convenient to capture a response immediately when students are in the room.

Having seen Menti in use during the FMS TEL Conference, the decision was taken to try it out in a much bigger setting – the inductions for all programmes in the School. Overall, this includes around 1500 students.

A useful aspect of Menti in this situation was the capacity to provide a wide range of question types, as well as the ability to see answers as they are coming in. Naturally, this has some disadvantages too – students’ responses may be coloured by what they see on screen if this is displayed. Possibly due to its anonymous nature, students provided some genuinely challenging feedback which proved very useful.

When in use, Menti allowed for the sessions to be more interactive as sharing live responses is quite immersive. It also allowed for the presenters to directly react and respond to things as they came in and broke the ice between students and staff. This can be useful for quick questions about content as well as student voice activities, for example polling the level of understanding of a concept at the start and end of a teaching session.

In terms of providing evidence to share with other colleagues, or at committees, Menti retains the responses for you to review, and can generate lists of entered comments. It isn’t designed as a statistical analysis tool, so comments don’t come in a convenient format for analysis. Graphs can be screenshotted for simple sharing if needed. It is of course possible to read through the comments and type up an overview of common themes yourself if needed.

The instant feedback received highlighted that some students weren’t entirely satisfied with the feedback they were receiving on their lab reports. Based on the responses, the School was able to put on a dedicated feedback session to further explore this, and to find out what could be improved, and have already been able to implement some changes.

You can create a free account on Mentimeter.com. This free account has limits on how many individual questions you can make, but you can always make multiple presentations and switch to them when sharing your screen. The university does not have any subscription to this service. As such, do not ask students to input any personal or sensitive information as this won’t be covered by our data policies.

When presenting, simply ask the audience to visit the site and enter the provided code that you show on the screen. When you’re ready, you can display the results to your audience. See the FMS TEL Community for a full walkthrough.

Lindsey Ferrie, Senior Lecturer, School of Biomedical, Nutritional and Sport Sciences

This post summarises posts from 2021 – thank you to all of our contributors!

The blog is now a year old! It’s been fantastic to see our readership grow over the year, and we hope you have enjoyed learning more about the work we do in FMS TEL, and have found our tips, resources and events useful and enjoyable.

We would be very grateful if you could spare a few minutes to tell us what you think about the blog, and what you would like to see more of in 2022.

We have covered the introduction of new software such as H5P and Inspera. We have also posted a range of teaching and learning case studies such as using Zoom for online teaching, using online tools to generate discussion, and build community.

We have highlighted specialist work within the FMS TEL team, such as graphic design, animation, video editing and 3D imaging, as well as covering specialist software and accessibility. Hybrid teaching and blended working have also been important topics this year.

Issues of data privacy, confidentiality and copyright have been covered, we have adapted many courses to new online formats, and converted face-to-face teaching to interactive online resources.

We have shared many tips on how to quickly achieve complex-seeming tasks, such as removing the date from a screen cast, and creating your own gifs from videos. We have also shared even more guides in the FMS TEL Community on Canvas and the MLE, and our webinars and Conference.

The blog is edited by a different FMS TEL team member every month, and many team members have taken on this task, as well as contributing posts to the blog – thank you to all of you! Our thanks also go to those colleagues who have offered their examples of practice for us to showcase here. We look forward to working with many more of you in 2022… feel free to drop us a line if you have something to share.

This post is about using audio recordings of patient consultations in teaching. Commentary was added to the recordings by the lecturer to create a richer resource.

This case study concerns Dietetics and Nutrition module NUT2006, Measurement and Assessment of Dietary Intake and Nutritional Status. As part of this module, dietary interview consultations are recorded so that the students can listen to these as examples. The FMS TEL Podcasting Webinar provided initial inspiration for what could be done with the recordings to enhance them. With a little more support, a new audio resource has been developed which adds audio commentary to the recorded consultations, highlighting various features.

The work of Dietitians and Nutritionists involves gathering information from individuals and populations on their recent or typical food intake. This enables them to analyse nutrient intake and understand dietary behaviours so that they can make suitable recommendations. Taking a diet history, or a 24-hour dietary recall, involves a structured interview with questions exploring habitual food intake, timing of meals, cooking methods and quantities. The effectiveness of the interviewers’ questioning technique impacts upon the quantity of information gathered and the quality of the nutritional analysis that can be undertaken. Students are working towards proficiency in these skills. Listening to recordings of these interviews exposes students to examples which will support in improving their skills when they perform these tasks for themselves. They can also practice analyzing the data provided from the audio recordings.

The recordings themselves are a very rich resource, which could be used in a variety of ways to help students improve their practice. The following task was developed, which required teaching staff to add audio commentary to the interviews.

Students first watched a short lecture on best practice for conducting interviews. They then listened to a recorded interview, by an anonymous peer, and made notes critiquing the effectiveness of the questioning techniques and determining if the quality of information obtained was sufficient to undertake nutritional analysis. Next, they listened to the same interview with professional commentary provided by staff, highlighting what could be improved and were asked:

This task was designed to allow students to develop their skills in conducting the interviews, and to reflect on practice and identify areas for development. The use of peer recordings meant that there would be a range of areas to comment on, making the task itself much more active than simply listening to a professional. Students were also offered more interview recordings to practice this task further.

A recording was chosen that demonstrated a range of teaching points. Having listened to the recording and made brief notes, cuts were then made in the original recording at natural stopping points, for example, after the participant and interviewer had discussed breakfast. It was important to allow the original recording room to breathe by not interjecting too often – this makes for fewer edits too.

You can record audio with a range of devices – Windows laptops can run Audacity, and Macs come with GarageBand. It is also possible to record audio clips on a smartphone and import them. When doing any recording, make sure to do a quick test first to ensure there is no unwanted background noise – just record a few seconds and listen back. GarageBand was used in this case, but the Audacity user interface is very similar.

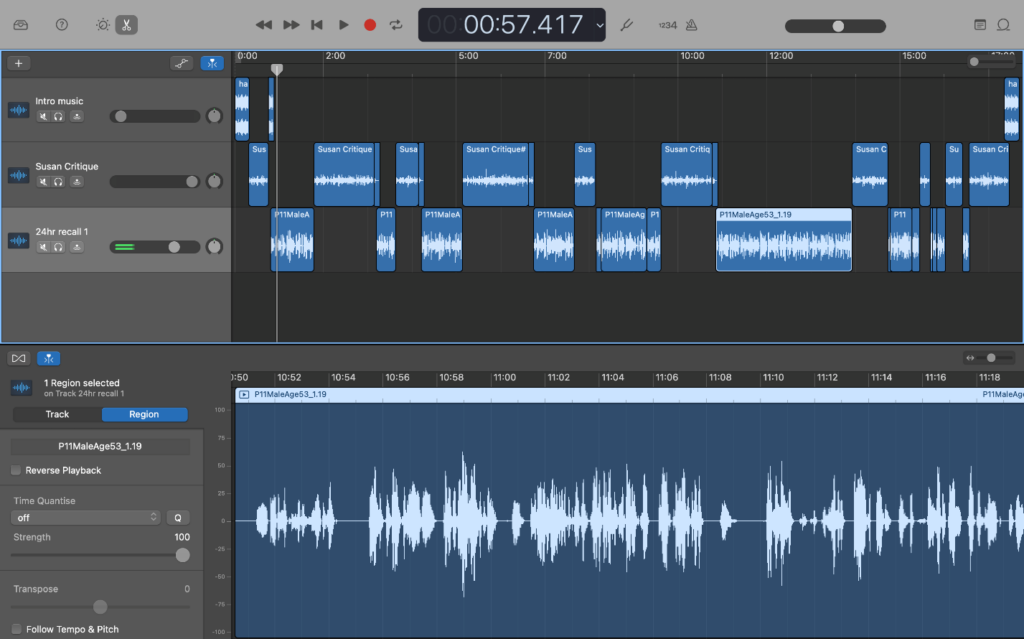

The first 20-minute recording took around two hours to produce, but this time included learning how to use the software. The screenshot below shows how the editing process looks in GarageBand. The top half shows the three tracks that were mixed to create the final output. By cutting and arranging the various sections, it is possible to quickly add commentary and even intro music to the basic original recording.

The project file, which contains all of the information in the top half of the screenshot such as individual tracks and cuts, can be saved for later use. This is helpful if you want the flexibility to change the content, or re-use elements. The single stream of audio can be exported separately as an audio file and embedded into Canvas or the MLE with accompanying text and other resources to build the desired task.

It is natural to worry about quality when producing an audio or audiovisual resource for the first time as the content should convey a level of professionalism matching its purpose. As long as content is clear and understandable, it will serve for teaching. Making a clean recording can be done relatively simply by avoiding background noise and speaking at a measured pace and volume. You can add a touch more professionalism to your recordings by adding a little music to the intro and using some basic transitions like fading between different tracks if needed, but there is no need to go out and buy specialist equipment. The content of the recordings was linked very closely to the students’ tasks and mirrored how they may receive feedback in future by showing what practitioners look for in their interviews. This clear purpose alongside the care taken in producing the audio ensures that this resource is valuable to listeners.

While at first it seemed like a big undertaking, a quick YouTube search for instructions on using the software, and then having a go with the audio recordings has opened up a new avenue of teaching methodology – it was a lot easier to do than it first appeared, and in total took around 2 hours. The software has a lot of capabilities, but only the basics are really needed to produce a high-quality, rich teaching resource. Commentated practitioner interactions allow teaching staff to draw students’ attention to key moments while remaining in the flow of the interaction, signposting how students can reflect on practice and develop their own interviewing skills.

Susan Lennie, Senior Lecturer, Biomedical, Nutritional and Sports Sciences